War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

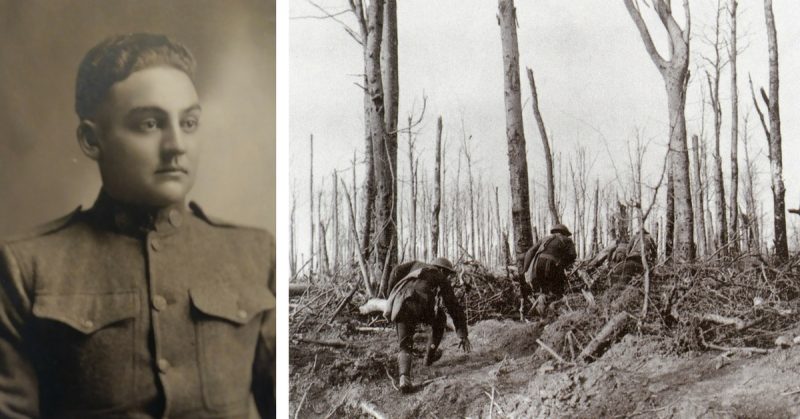

For many years, a military portrait of George Florea has hung in the home of Jefferson City resident Dot Baker, representing a great-uncle that she never met because of his death in World War I. Acknowledging that she will one day pass the portrait on to one of her children, she hopes to learn more about her relative’s military service to better understand the sacrifice he made on behalf of the nation.

“I didn’t ask a lot of questions about him when I was growing up,” said Baker, when discussing the military service of her great uncle. “I would like to know more about where he fought and served in the war” she added.

Born in the community of Knox City in northeastern Missouri on April 24, 1895, Florea was one of nine children. Due to his age, the 22-year-old cattle farmer was required to participate in the first draft registration day that was held on June 5, 1917.

His draft order number was drawn during the first draft lottery held in Washington, D.C., on July 20, 1917. Several weeks later, on October 4, 1917, Florea was inducted into the U.S. Army at the nearby county seat located in the small town of Edina.

Following his induction, Florea was assigned to Company G, 354th Infantry Regiment—a company of the 89th Division comprised primarily of troops from eastern Missouri. According to the U.S. Army’s Center of Military History, the regiment began forming at Camp Funston, Kansas, in August 1917 under the early guidance of Major General Leonard Wood.

Florea and the soldiers of the 89th Division underwent several months of intense training that helped introduce them to many evolving threats of the war raging in France, including trench warfare. However, survival in combat under threats of gas attacks and shellfire launched by enemy troops were not the only possibility for which the soldiers were prepared.

“When a case of contagious disease, such as meningitis, measles or scarlet fever, appeared, all the men of the company were quarantined, were required to drill separately and were not permitted to join any assembly with other men,” noted the book “History of the 89th Division.”

The book further explained that when such situations occurred, “The floors of all buildings were washed daily with disinfectants. Every utensil used at the table was sterilized after each meal with scalding water” in an effort to prevent the spread of the diseases occasionally racing through the camp.

The young Florea made it through the training unscathed and, according to “Order of Battle” published by the U.S. Army’s Center of Military Service, his division boarded transport ships on the east coast bound for overseas during the waning days of May 1918. Following their arrival in France in early June, they participated in several weeks of strenuous training before entering into their baptism of fire in late summer.

“It was announced recently that the 89th Division had taken over trenches in the Toul sector about August 15 (1918),” reported the St. Louis Star and Times on September 20, 1918. Nine days later, the paper further explained, the 354th incurred their first casualty when William Unland of St. Louis was severely wounded in action.

In early September, the division took part in the St. Mihiel offensive in northeastern France. This battle lasted several days and was the first major offensive in which the American Expeditionary Forces—led by Missouri native Gen. John J. Pershing—operated as an independent army. Three weeks later, the St. Louis newspapers were full of reports of area soldiers serving in the 354th who killed and wounded in the campaign.

As the calendar passed through the middle of September, U.S. forces began to shift their resources south toward the Argonne Forest and Meuse River. Throughout the next several weeks, Gen. Pershing commanded what became known as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive—the largest American-run offensive of the war with the ambitious goal of cutting off the German 2nd Army.

On September 25, 1918, during the transition into this new offensive, Florea was killed in action. Although available documentation does not clarify the specifics of his death, the St. Louis Star and Times reported in their October 22, 1918 edition that Pvt. Francis Crowley—a fellow soldier of Company G, 354th Infantry—was wounded by a gas attack the day after Florea’s death.

The 89th Division history book also describes in great detail a couple of raiding parties that were made into enemy territory by soldiers of the 354th Infantry during the timeframe of Florea’s death, which resulted in a handful of casualties from enemy artillery barrages; however, the names of those killed in these actions were not specifically cited.

“The remains of George Elliott Florea, a Knox County soldier of Company

G, 354th Infantry, who was killed in France in the Argonne Forest drive … arrived Friday morning at Knox City from Hoboken, N.J.,” reported the Edina Sentinel on June 30, 1921, describing the reinterment of remains of the local resident who had been buried overseas for nearly three years.

In the years after the war, Baker’s grandmother, who was one of George Florea’s three sisters, continued to honor the memory of her late brother by displaying a simple reminder of him in her northeast Missouri home.

“I remember the picture always hung in my grandmother’s living room in LaBelle and it has hung in my house since my parents passed away,” said Baker. “Growing up, I knew he was very important to my grandmother and being that he is family, it now means a lot to me.”

With a heavy pause, she added, “It’s a connection to our past and I will some day pass it down to one of my children as a continuance of his legacy.”