War History Online presents this Guest Article by Mark Gero

Saturday, February 5th, 1944, in a remote part of central France lies a village called St. Leonard En Beauce, around 30 miles North of the largest town in the region, Blois. A beautiful morning with the snow still on parts on the ground, the day beginning very clear, but cold. The children in the village are in school for only a few hours, and looking forward to enjoying the rest of the day later.

The area, as well as the rest of the country, have been under Nazi occupation for nearly four years now, and the sound of Allied bombers are in the distance to the west indicate that one day soon, freedom will drive out the occupiers for good.

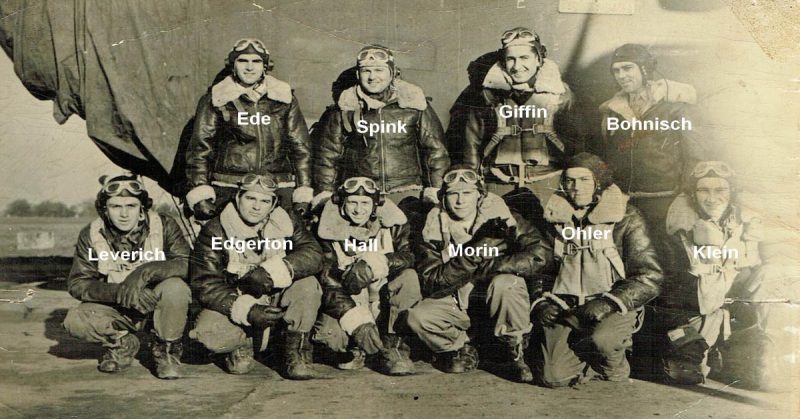

Thousands of feet up into the sky in this area is the B-24 Liberator known as the “Star Valley,” which is on their eighth of 25 scheduled missions, now on their way back to their base in Shipdham, East Anglia, England. Their job today is to bomb a Renault works manufacturing plant near Tours, in the Loire et Cher region. Now returning north, all the ten crew members are looking forward to getting back and enjoying a drink at the bar.

Suddenly, without warning, a flight of German aircraft approaches, in which one Focke Wulf FW 190, takes a shot at the Star Valley. The plane itself, in the back of the wing formation, becomes the target of the German Pilot, Kurt Buhligen. One member of the crew, left waist gunner Kenneth Hall, mistook the plane for an American fighter, and tried to contact it. By the time that the plane began to fire on the Liberator, Hall did not have time to react and stayed frozen next to his weapon. The right waist gunner, Warren Klein from Detroit, Michigan, called Joseph Morin, who was the tail gunner, to try to shoot down the airplane coming at it. Meanwhile, in all the confusion, the plane was hit in the number two engine, which began to catch on fire; Klein tried to get through to the pilot of the plane, Carl Bohnisch from California, to ask for support.

Bohnisch, meanwhile, was trying in vain to keep the airplane from spinning, while Morin in the rear of the plane was firing like crazy. Now, without warning, the plane’s tail began to malfunction, and Morin realized that it was time to get out of his position and move to the front, to find someone else on the crew to communicate with the possibility of having to abandon the airplane. He met up with Klein at the back hatch for a few moments, when the plane began to spiral as Bohnisch could no longer hold it steady. Klein jumped out of the right side of the airplane in a haze as rumors have always emerged that he could have been assisted by Morin. Ball Turret Gunner Eugene Edgerton from Connecticut, was in Klein’s mind to assist as well, but since the position was almost impossible to escape from, Klein had no chance to run over and assist him. Edgerton was not the only airman that never had a chance; many in the front of the airplane could never escape as the plane’s plummeting G-force would make them unable to escape.

Meanwhile, in the village, the children jumped out of their seats as a load motoring noise began to head towards the earth. The inhabitants of the village who had been looking at a bunch of planes heading towards the west, viewed a plane reducing speed and seeing flames coming out of the left side of the aircraft. With all the confusion, parachutes began opening out: perhaps a reported three parachutes being seen. A giant black cloud was very visible followed rapidly by a huge explosion quickly dissipating over the next door village of Sigogne.

Immediately a German aircraft is spotted flying quickly over the town from a position of east to west. Rapidly, most of the eyewitnesses began to realize that there was a huge wreck located in the farming area of Monchaux, just south of Sigogne. The mayor there, known simply as Monsieur Redouin, grabbed his bicycle and peddled to the crash site.

Returning to the village, Redouin indicated that bodies had been taken out of the airplane with the assistance of townspeople that were lined up and covered in their parachutes. The mayor had taken the identity of the flyers in which the burns from their bodies all made this more possible. He asked the inhabitants to keep their dogs away from the area and not have them go wandering off.

Later in the afternoon, the son of the mayor of Sigogne and others went to see the remains of the crash site, where they found the wreckage of the plane broken up, along with the motor which was pulled off. In addition, a propeller was lying far away under the detached motor and half-buried into the ground. One person found a brown leather bag under the mass. The ground was littered with metal, machine gun cartridges, pieces of wreckage, such as the small electric motors, which is used inside this bomber.

The visit did not last long, as finally following all this trauma, the German soldiers in this area approached in military trucks that might have come from Blois. Afterward, the Germans moved the bodies of the nine flyers to Blois and put them in a hut, sealing them in. The doctor there identified the bodies but only found five had name tags on them. They were then placed in coffins and moved near the west wall of the Basse City Cemetery in Blois where they were given full German military honors. Following the end of the war and for the next 20 years, many of the families of the victims had the option of returning their bodies back to the United States.

Lieutenant Harald Spink was finally laid to rest in Nebraska, while Lieutenant James Ede was returned to Kentucky with Hall being honored in Massachusetts. Adjutant Bernard Ohler and Bohnisch were for many years in France until late 1940 were when they were returned to Maryland and California, respectively.

For Edgerton, Lieutenant John Giffin, Adjutant William Leverich, and Morin, were buried with full honors at the American Military Cemetery at Colleville Sur Mer, Normandy, France.

For the pilot of the Focke-Wulf, Buhligen, it was just not a lucky kill; he had been honored at the Berghof just one month later by Adolf Hitler, and downed 104 allied aircraft during the war. Buhligen joins only a handful of German aces that shot over 100 planes during the conflict. Buhligen was finally captured in 1945 by the Russian army and served six years in a gulag until he was released in 1950. He lived a full life until he died in 1985 at the age of 65.

As for Klein, his was the only confirmed parachute that escaped the danger on that day in February. He managed to land in a disused quarry and was discovered by a villager, Mr. Leroux, who took him to his residence to clean up his wounds. Only a short time later, the Germans arrived and apprehended Klein, taking him to the hospital in Blois before moving him to a prisoner of war camp in Sagan, Poland. Before he was taken away, Klein managed to pencil his name on a war calendar at Leroux’s house. Klein has transferred to two more P.O.W. camps afterward before being liberated on May 1st, 1945. Klein returned to the United States and eventually married, having a family with three daughters and two sons, before dying of heart failure in 1975 at age 52.

For the next 50 years, nobody else paid attention of what happened that day. Many who had been involved in this incident, went to their graves realizing there was really no closure on what was the conclusion of the Star Valley episode. Finally, on May 8, 1995, a town researcher made a speech on the 50th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe, did finally the story of these ten crew members came back to life.

On the same date in 2014, some members of a reunion committee of the crew members marked the unveiling of a brand new monument honoring the Star Valley, which replaced the old version next to another monument, dedicated to the French soldiers killed that lived in the village during the first and second world wars.

But not every family member of the crew attended.

In 2016, this author attended the Bastille Day celebrations on July 14, in which being the second cousin of Airman Edgerton, became the first member of his family to be honored; something that his late grandmother and his mother, who knew Edgerton like a son and a brother, honored very much. He was taken a tour of the village of St. Leonard En Beauce, by the town historian, Jean-Claude Bigot, Corrine Chaillou, secretary of Yves Chantreau the major and his wife; by having lunch with them and their friends, and even speaking French at the local celebrations later that afternoon, with gifts of wine, cards and lot of friendship.

Which can show that story of the Star Valley can come full circle and never fade away in the annuals of history.

Author: Mark Gero