War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Joseph M. Durante

In 1938 the German speaking areas of Czechoslovakia, also known as the Sudetenland, were growing impatient and upset due to the economic recession, “when the economic recession hit Czechoslovakia and the German industrial districts were the most affected by it, even these German parties became dissatisfied with the treatment of the Czechoslovak government meted out to them.” Also, with the lack of help from their government didn’t help the population ease their views on how much the Czechoslovakian governments’ ability to help them.

“On 20 February 1938 Hitler publically declared his vital interest in the fate of the Sudeten Germans and promised them help.” With Germany became a world power and by showing their interest and the future takeover of it, the rest of the world powers now had to act, those belonging to Josef Stalin of the Soviet Union. Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill of Great Britain, Franklin Delano Roosevelt of the United States of America, Edouward Daladier of France.

When Germany declared their interest in helping the German speaking Czechs, Hitler met with Konrad Henlein, the leader of Sudeten German Party. “For the Czechs, the problem was how to satisfy the German minority without destroying the Republic.” The meeting was meant to have Henlein raise his demands of the Czechoslovak President Edvard Benes.

“President Benes… Saw this clearly and tried several times to strike a bargain with Germany, and even with Hitler. These desperate attempts were doomed to failure, but President Benes tried them all – even an appeal to Soviet Russia to counterbalance the rising power of Germany,” which both Stalin and the Russians seemed not to want to help Benes and what was thought to be his problem “Thus in the circumstances of 1938 the Czechs were really let alone to face Hitler and Germany.” For Hitler, he asked himself how he could obtain his goals, “how to destroy Czechoslovakia and the system of Versailles with it by exploiting legitimate Sudeten grievances.”

Russia had no political border with Czechoslovakia and so it would have been very difficult to support them with military troops and armor. Also, Russia would have had to move troops through either Poland or Romania, “would almost certainly have forbidden Russian troops the necessary rite of passage through their territory, thus rendering military action politically unpalatable also.”Russia looked only to their own in the issue of the crisis in Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland for Joseph Stalin didn’t want to upset the Germans and Adolf Hitler.

Another main power in the late 1930’s was Great Britain under Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Parliament Member Winston Churchill. A telegram was sent to Chamberlain from President Benes stating that if the German demands are not met, they will move their troops into Czechoslovakia and take it by force. In response, Chamberlain mobilized the Royal Navy. Also, the Cabinet’s Foreign Policy Committee ruled that there was little Great Britain could do to help Benes and his problems with Germany. They told Benes to try and make arrangements, the best arrangements they could, with Hitler and the German government. Chamberlain and his Cabinet agreed that if a possible war were to breakout between the European powers, Chamberlain would step in and meet in Berlin with Hitler.

In late September of 1938, the Munich Conference was held in Munich, Germany. The conference was to delegate Germany’s interest in the Sudetenland territories. This conference had all the major European powers except for Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union and Edvard Benes of Czechoslovakia. “The European powers felt obliged to sort out the Czech-German conflict and from that moment the fate of Czechoslovakia was taken out of the hands of its people.” This conference, in the eyes of the British and French Governments was to appease Hitler and the Germans into their interest in the Sudetenland. A major critic was Winston Churchill of Great Britain, “Churchill emerged as a leading critic of the Munich Agreement, addressing Members on 5 October 1938,” in a speech called, “The Abandonment and Ruin of Czechoslovakia” by Winston Churchill.

Within his speech, Churchill says that Czechoslovakia will be engulfed in the Nazi regime,” and also, “They neither prevented Germany from rearming, nor did they rearm ourselves in time.” Churchill knew that the hope for saving Czechoslovakia was gone already, and he condemned not responding with military force to oppose Hitler and Nazi Germany. “On 18 September 1938 the French and British Premiers and Foreign Ministers met in London to consider how to appease Hitler, for it became evident that, short of war, nothing could be done for the Czechs.”

Even those in lead of France knew that they could not, even with combined efforts from Great Britain, could not help the Czechoslovaks. Churchill, to try and combat the ever growing strength of the German military, said this in his speech three things that need to happen, “first the timely creation of an Air Force superior to anything within striking distance of our shores;” to create an Air Force that can fend off a powerful German air force, “secondly the gathering together of the collective strength of many nations;” which will give a substantial force to the nations opposing the Nazi regime, and “thirdly, the making of alliances and military conventions, all within the Covenant, in order to gather together forces at any rate to restrain the onward movement of this Power.”

The problem with Churchill was that he was not the Prime Minister at the time. He served in Parliament, under Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in 1938. Even an article in the New York Times described what had happened in Europe, “Nazi Demands Met: Hitler Gets Almost All He Asked as Munich Conferees Agree.” Within the article, it says that “Prime Minister Chamberlain, whose peace efforts were finally crowned with success, received the loudest applause of Munich’s crowds.”

Also, “Paris was relieved at the Munich agreement, but continued its war preparations,” and even “Pope Pius broke down and sobbed as he appealed in a world broadcast for prayers for peace.”President Franklin Delano Roosevelt of the United States of America “urged the people of this country to offer such prayers” to show comparison to Pope Pius’ actions. Roosevelt and his ambassador Joseph Kennedy had made their decision to back Neville Chamberlain and his decision. President Roosevelt had sent Hitler a message, “begging Hitler to consider the lessons of the First World War, and suggesting ‘a conference of all the nations directly involved in the present controversy.” Although the United States had no real power within the Munich Conference, praise would be given to President Roosevelt if peace were met.

France, which had an alliance with Czechoslovakia, had a representative at the Munich Conference. Edouward Daladier was the President of France and contributed to the outcome of the Munich Conference. France had been alerted of the German plans to take over the Sudetenland territories and that, “Prague had not yet been informed of these plans, but the Fuhrer was to be consulted first.”France had the alliance with Czechoslovakia and was to support Czechoslovakia in case of a military assault. Instead, to try and combat the German advances and plans to invade Czechoslovakia, they met in Munich for the Conference.

Daladier had “reassured Chamberlain that, ‘if Germany attacked Czechoslovakia and hostilities ensued, the French intended to go to war and to commence hostilities with Germany within five days.”They had agreed to terms of the annexation of the Sudetenland to Germany. After the conference, France looked to the United States to help them rearm their military and Daladier regretted that not having an air force to show a strong force to the German Fuhrer.

With all the strong, powerful nations in Europe and that of the United States of America, nothing they did could have been done to stop the rise of the Third Reich. President Benes of Czechoslovakia was left no choice; he couldn’t fight against the Nazi regime due to having a much less powerful army and had little military support. Also, Benes had no say or control of the outcome of the Munich Conference. Stalin and the Soviet Union stayed away from Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland and were excluded from the Munich Conference as well. Neville Chamberlain had tried to avoid any military actions but if there were events leading to a supposed European war, Chamberlain would step in diplomatically. Winston Churchill in many speeches broadcasted over BBC radio openly opposed the Czechoslovakian Crisis involving the power of the Third Reich and the annexation of the Munich Conference.

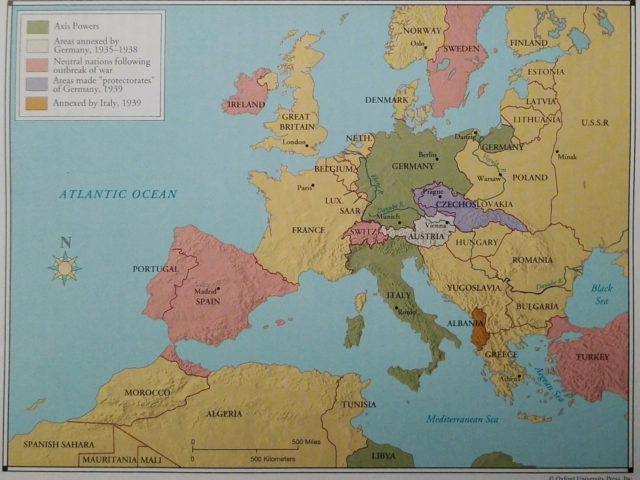

Also, Churchill spent a lot of time to help delegate ideals to the British people, and hoping to support Great Britain if war became inevitable. President Roosevelt and the United States had an order of Neutrality in the European affairs but still tried to maintain a level of humanity in outcomes of a new world war. Edouward Daladier and the French people aligned themselves with Czechoslovakia and backed them completely. Even present at the Munich Conference, France was forced to keep hostilities towards Germany and the Third Reich while opening trade with the United States for a stronger air force. In the end, war broke out and Czechoslovakia was completely taken over by Hitler and the Third Reich. Under a year later, Poland was invaded by both Germany and Russia, which provoked Great Britain and France to enter the war against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Russia.

Bibliography

Faber, David. Munich, 1938: Appeasement and World War II. New York City: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2008.

Gilbert, Martin, ed. Churchill: The Power of Words: His Remarkable Life Recounted Through His Writings and Speeches. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2012.

Speech – “The Abandonment and Ruin of Czechoslovakia” located in text listed above

Jorbel, Josef. The Communist Subversion of Czechoslovakia 1938-1948. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959.

Bradley, J.F.N. Czechoslovakia: A Short History. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1971.

Pauley, Bruce F. Hitler and the Forgotten Nazis. N.p.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1981.

Mastiny, Vojtech. The Czechs Under Nazi Rule. New York City: Columbia University Press, 1971.

All used citations are directly from the cited bibliography.