War History Online presents this Guest Article from John Sekel with the assistance of David Sekel – his son.

History has recorded times when one man’s selfish ambitions have given him control over his fellow humans and led to the subjugation of nations. Adolph Hitler was among the worst of such men after the Third Reich conquered Europe. Britain was rapidly losing the ability to defend itself and their supplies of food and energy were nearly depleted.

In America, we were going about our usual “who cares” way of life. Our leaders knew that we had to do something. Sooner or later it would impact on us. The attack on Pearl Harbor galvanized US citizens into action and as time would tell, we mobilized the greatest arsenal of war in the shortest time in history.

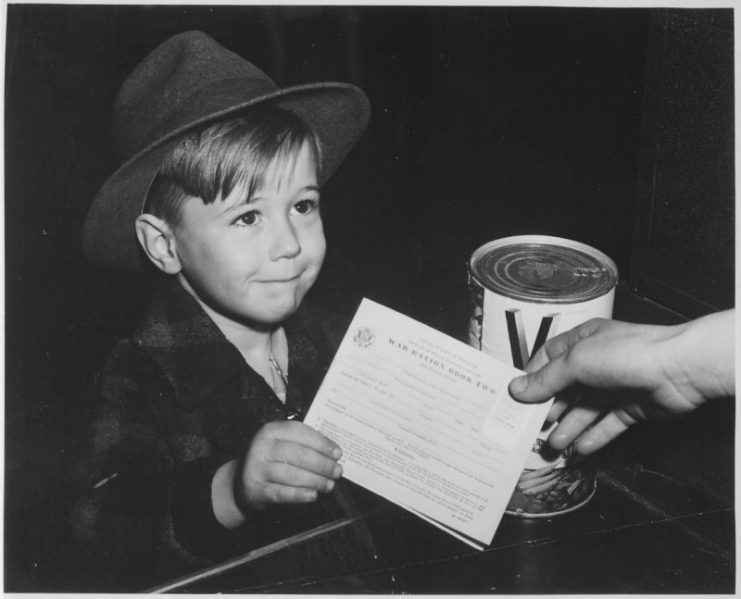

Suddenly, everything was rationed. You had to have coupons to buy anything; gas, tires, sugar, you name it. People had to register (I don’t know where) to get coupons. Those with extra needs got adequate coupons. Farmers, those that had to drive a lot, got enough gas. Victory gardens sprang up everywhere. Schools and kids had scrap drives for everything and that is the way the home front operated.

It so happened that I was the right age (draft age was 18 to 30) to become a part of the war effort. I was working in Cleveland in a factory and rooming with my brother, Mike. When the war erupted, Mike enlisted in the Army Air Corp. I didn’t seem to have any aim or direction or ambition in life. I moved in with a Buffalo friend, Emil Scrapjansky.

Shortly afterward, we decided to join the services. A downtown Cleveland building housed all the enlisting offices. Army, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard turned us down for silly defects (I had an overbite). The top floor had a Merchant Marine office, totally foreign to us. We applied and were informed we would be sent to New York that evening. That stopped us cold. What kind of an outfit was this? Later we found out German subs were having a field day off our East Coast. “Hell no,” Emil said “we have to go home and hoe corn first.”

So we quit our jobs and went home to Buffalo (Ohio) for a couple of weeks, then back to Cleveland. By way of Akron, we found Maurice Williams, my lifelong friend and the three of us were on a train on our way to New York and the US Maritime Service. We were based on Hoffman Island for a three month training period that would make us experienced seamen (not a big joke – just a little joke).

The seriousness of war had not yet gotten through to me. The military part wasn’t bad. We marched, drilled in lifeboats, gunnery, studied ship stuff, got time off in town to booze up, etc. I got sick on the parade field and wound up in the Marine hospital on Staten Island for 16 days for appendix surgery. When I got back to Hoffman, my class had been shipped out including Emil and Maurice. I was sent to the Seaman Institute to await a ship.

It was in the coldest part of winter when I was assigned to a ship being overhauled. I was the first crewman on a completely dead ship – no heating or anything. There may have been officers that were already assigned, but not present. At first, I had to commute from the Institute ‘til we got heat. Gradually it came to life. More people came aboard. I spent my time down below in the engine room and fire room and it was a new strange environment. I was to work under the Second Assistant Engineer. The ship was the USAT Colorado a lake vessel converted for sea duty. It had been outfitted to include refrigerated cargo.

It was soon time to take the required shakedown cruise out in the harbor to ensure everything was seaworthy. It would take about two hours. This event took place on my watch. A short description of my duties is needed to explain what happens.

The ship’s routine at sea was watches of four hours on and eight hours off. The First Assistant Engineer with his crew worked the four to eight shift. The Second Assistant Engineer and his crew was twelve to four and the Third was eight to twelve. The fireman’s duties were to maintain steam at all times. There was a red mark on the steam gauge at 180 pounds and you were to keep the needle exactly there at all times (I never read that in the fine print) and that was no easy task. Sudden engine speed-ups depleted the steam as sudden slow-downs did the opposite. The fireman, racing back and forth between two boilers with four burners each, opening and closing valves and watching the gauges, had a busy time. This occurred mostly when the ship was port maneuvering, etc.

Out at sea, everything held pretty steady. The fuel oil was similar to that sprayed on roads for dust control. It had to be heated to a certain temperature to burn. But I’ve gotten ahead of my story. A couple of days before the trial run, the Second Assistant instructed me to light up the dead boilers and gradually bring them up to steam. This was done by opening valves, starting the pump, and filling the boiler till it showed in the gauge glass. In a cold boiler, the fires were started manually with a lighted kerosene soaked torch and inserted through a port to ignite the fuel oil as the burner was turned on. All the burners were alternately lit one at a time.

After some time had elapsed, the Second Assistant came by to see my progress. Water should have been showing. He started checking and I heard a very loud yell from the back of the boiler. “You S.O.B.!! You’re supposed to open valves!” There was a shutoff and a check valve in each line. I forgot one of them. What a blow to my self-esteem.

Anyhow, I finally got the steam up. The trial run was performed on my watch. As I said, all the activity was new, the engine running, the telegraph ringing commands from the Bridge. I guess we got out into the harbor. Again I was being yelled and hollered at. Even the Chief Engineer came down to the engine room. We were belching a huge black cloud up and down the harbor and the Port Authorities were raising hell about the smoke. I couldn’t help it. The fuel oil was not hot enough and the air supply was not right. All of this was fixed in time and that was what the trial run was for.

I was finding out that this was not going to be a pleasure boat ride on Seneca Lake. Also, there was no such thing as quitting your job if you didn’t like it!

The ship with a full crew including a Navy gunnery team was ready to start its voyage. No streamers or confetti or a band playing. We just left silently in the night and were heading south to Charleston, SC, to load up. A new experience, being out on the vast expanse of the water all alone and for the first time, getting that feeling that someone was watching you. The ocean was getting a little choppy and the ship started rolling. Another new experience – without warning I was seasick, an awful feeling. Your guts come out through your mouth. But, you know, I got over it and never had another bout of it.

We pulled into Charleston, docked and all the confusion of loading began. The cargo consisted of huge Block Buster bombs at the bottom of the hold. Then progressively smaller bombs until the fore and aft holds were half full. Then drum after drum after drum of high-octane gas filled the holds. On deck, many crates of jeeps, aircraft, train engines, and metal runways all piled high with catwalks built on top for us to get around. Also, our refrigerator was filled with frozen turkeys. Our duty watches in port were 8 hours on and 16 off. The weather – from snowbound frigid New York to balmy, sunny, warm South Carolina overnight was strange.

For about the week that we were there, I tried every which way to reach my brother Mike who was training at the air base in Greenville, some 50 odd miles away. Not allowed to leave the area, I exhausted all my options and failed to reach him. Later, I learned that he gotten to the dock less than an hour after we departed.

We were leaving port and headed to Key West, Fl to form a small convoy to cross the deadly Caribbean with a stop off at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. A breakdown of our steering engine caused us to return to Key West and a few days later we were on our way again in another convoy. We later found out that the convoy we aborted was annihilated by the subs.

I don’t remember the length of time it took to cross what was called “Suicide Alley”. The German subs were concentrated in all the Caribbean as it was the center of shipping lanes to the Mediterranean, Africa, South America, etc. All of this area was called Suicide Alley. All the guys (myself included) dreaded going below to stand our watch.

On my watch as I relieved the fireman, we were to exchange “okays” before being relieved. He was gone. He had zipped out of there before I could say, “Hi.”

Well, I didn’t see any fireworks, but the noise was thunderous. The pipes and equipment, in fact, the entire area banged, clanked, and vibrated. I guess all the ships in the convoy zigged and zagged to evade the torpedoes. What I was hearing was depth charges exploding all around. There is no way to describe one’s emotions. You watch your gauges, water, steam, and fuel in a detached way. Every explosion makes you jump, expecting the worst. If this ship blew up would you know it? Be aware of it? So I would sing hymns and pray. The longest 4 hours of my life finally ended and I, too, zipped out of there and on to the deck. No orderly convoy was seen – just ships going in different directions. The escorts were still dropping depth charges. All subsided as Guantanamo came into view. I never ever found out what the convoy casualties were.

As we pulled into the tropical port, wouldn’t you know it, we ran onto a sandbar. We were stuck on it until the next high tide when we received a pull from a tug. No damage to our bow, but as luck would have it, our engine room caught fire – the most dreaded thing at sea. Everyone had a station. Mine, of course, was the engine room. I put on my gas mask and headed below.

On the way, I met the First Assistant Engineer screaming through his mask, “I can’t breathe!” I told him to take it off and go outside. (He was a little old Greek guy). Down below, the bulkhead (sidewall) was on fire on one side of a fuel oil storage tank and many coats of paint fueled the fire. We quickly put it out. If that steel wall had gotten red hot and ignited the oil behind it, the explosion would have been heard all over Cuba.

A short stay there at anchor was really appreciated. Balmy weather, clear water, locals in boats selling stuff, and the guys on deck with ropes and buckets hanging over the side made us forget there was a war going on. Cigars, porno picture packages, rum and souvenirs were purchased at very low prices.

We left there on our own for Panama on a very rough and windy trip. It made it safer from submarines, but the thought of them lurking nearby would always remain with me.

It was hot in Panama – very hot! We docked for 2 days while waiting our turn through the canal. On the Atlantic side of Panama, the cities were Crystobol and Colon (American). The Pacific side was Balboa. Going into town was another new experience. The people were Indian descendents. There was a hooker district a full 2 blocks. The crew would go ashore and get boozed up.

The ship took on a load of bread. It was loaded on skids, stacked like blocks, not wrapped and winched on board. It made the best toast I’ve ever eaten. I’d eat it when I got off watch at 4am and fixed it in our crew mess room.

We went through the canal – an all day job, tied up with a submarine, which was my first. Hot!! The Army had soldiers swarming over the ship as it went through. They watched and questioned each move for sabotage actions. At that time the Canal was U.S. Government property and operated by the Army Engineering Corp. No huge aircraft transports existed then, so the Canal was very vital. They were armed and menacing.

The heat is what I remember. It was 120 degrees in some places. The fire room had 2 pipes about 2 feet in diameter that went up to the top deck and Bridge area. There, it became funnel-shaped, 90 degrees with the pipe. This funnel could be rotated from the fire room to hunt for the wind flow. These pipes (ventilators) also had rope ladders up through them for escape purposes.

As I mentioned, the ship would go through the canal starting and stopping many times requiring constant firing changes. When the ship moved, we would get some wind even though the outside temperature was around 100 degrees. When we stopped, the heat hit you like a hot flame. All this time a soldier is running with me and I’m yelling what I’m doing as any fool could plainly see. You had to keep moving to keep the heat from burning your feet right through your shoes. Anyone that’s ever gotten a hot foot can relate to this.

Now, the steam pop off valve was near the smoke stack on the top deck near the Bridge. I confess to letting the steam gauge go past the red mark and popping that valve. I again caught hell, but enjoyed the commotion I caused. “Go ahead and fire me!” That evening we were anchored at Balboa in the Pacific. Finally, cool breezes. Every one had sweat enough to fill that canal.

I’d like to insert a couple of information points here to help all of you that intend to become a fireman. After the boilers get heated up, the combustion chamber lined with a ceramic coating, gets red hot and shutting off a burner to replace with a clean one or whatever, a torch is not needed to relight it. Just spin the valve open. Caution! This – only when the chamber is red hot. To repeat, the boiler is a large steel box. The bottom part is the combustion area. Above, the area is filled with water pipes all connected one to the next and so on that allows water to flow through and become steam. At the top is a dome or chamber that superheats this steam as it flows through. When it goes to the engine, it is a very hot, high-pressure invisible gas. One other item before I get on with the trip, in rough seas as the ship rolls, the water level in the gauge glasses rises and falls with the roll of the ship. Sometimes this happens so quickly that you only get a glimpse of the water. You try to judge how long the gauge is empty to how long it’s full in comparison to the length of the roll. There are times that this can get hectic.

Leaving Balboa, we headed North to Salina Cruz, Mexico. We found out later that the orders were to head south to the coast of Chile and then west to Australia. The Captain, being an old coal burning ship sailor, wanted to stop at Salina Cruz, an old coaling port for old times’ sake. This was a bad move on his part, because later, as soon as we docked in Sydney, Australia, two MPs came aboard and led him off the ship and a new captain came aboard. The Pacific was very calm compared to the Caribbean. In the moonlight, the water would glow in streaks from the phosphorus in the water. By day, flying fish by the thousands were all around us. We were to sail all alone to Australia.

In Salina Cruz, a small town with dirt streets and huts and not much more, those not on watch went ashore and found a cantina. Before going to the cantina, we all found the Post Office and bought cards and mailed them. All except me. I got the card for home written ok, but for the life of me, I forgot Mike’s address. I always remembered it before. That card was written and I kept it for many years. Later on I found out, after arriving in Sydney and the mail finally reaching us, that Mike had already died in a plane crash. The owners of the cantina quickly rounded up a couple of musicians, both playing a long stringed instrument and the tequila flowed and we got zapped. I was to relieve the fireman on watch. That thought must have poked through my foggy brain and I headed back to the ship. How, I don’t know. In total darkness and 3 or 4 turns in a direction along the way, I got down to the fire room, not even seeing the fireman I was to relieve. There was a pipe crossing the boiler area that I would hang on by my hands and as I fell asleep, my hands would relax and I would drop and jar myself awake. Singing, “On top of Old Smoky” as loud as I could keep me going. Or so I thought. I awakened some time later behind the engine and rushed to look at the boiler gauges. The steam was down, the water was very low and the generators had slowed down just a little. I proceeded to get everything back to normal. I found my glasses in the shaft alley, bent but usable. Luckily no one came checking on me. I think the entire ship was drunk and asleep. I still shudder when I think of what could have happened. The catastrophe would have made world headlines. Many times as I go through life I reflect on how an entire crew depends on one person doing his job right. A pilot of an airliner comes to mind as an example.

We left Mexico and the Americas next day, still alone for Hawaii without incident and docked in Honolulu on a beautiful day. The signs of war were evident – barb wire everywhere – total blackout – curfew. The Port Captain welcomed us and said they had followed us all the way. Our Captain says, “You’re a damned liar!” Just like that. “We aren’t even supposed to be here!” Which was true. If we had sunk or something, no one in the world would have known it. The two or three days while in Honolulu were spent walking the streets. Nothing going on. I remember Diamond Head in the distance, the King Kameamea Statue, and the Aloha Tower. We would swim in the harbor, dive off the ship until I saw a turd floating by and that ended swimming. We left Honolulu with a rainbow reaching from shore to our ship. The farther we went the longer the rainbow got. We hoped it was a good omen.

We plodded along at a top speed of about 10 mph and I keep saying, all alone, heading southwest in super balmy weather – nothing to show that there were any more humans on the planet. All we saw were the flying fish and huge areas solid with jellyfish. Sometimes we saw faint outlines of South Pacific islands on the horizon. We moved our sleeping stuff outside on top of all those crates. Rain squalls would make us scramble back inside. Now we were finding out that the Captain’s decision to go the long way was almost disastrous. Our water supply was nearly depleted. It was shut off for everything except cooking and the boilers. We flushed toilets with buckets of seawater as well as tried to wash in it. There was a tank in the engine room that used steam to boil sea water and make fresh water. This was called an Evaporator (of course). It replenished some water, but two days out of port the boilers exhausted their supply and the Chief Engineer gave the order to start using sea water. An ominous condition now existed. The salt in the sea water caked the pipes. This took more heat to make steam. The pressure started dropping, engine slowing down, boiler tubes began to warp and twist. We knew that a disabled ship so close to land was easy prey to subs. Also, if the boiler tubes cracked; well, it did not happen and we limped into Sydney harbor, shut off everything and the tugs docked us for a 6-week stay to repair the boilers.

Sydney was a great city, full of our service men and women there for R & R. There were many things to do and see. Theaters, botanical gardens, pubs, restaurants, great beaches, and very friendly people made us welcome. Very few Australian men in the city. They were in the jungles fighting Japs. I could write a book on our activities there. I’ll touch on a few things, in no order, as I think of them. I can’t recall when, but along the way I received a slight promotion and became an Oiler (a new ballgame for me). Some of our crew went back to the States and were replaced by Aussies. Tom Shearman replaced me in the fire room; we became close friends.

We made several trips to New Guinea with usually the same kind of cargo. The rear end of the ship – stern, fantail or any other name, had a one -floor deck (poop deck) and that was where the Firemen and Oiler’s living quarters were. Above, on deck was a 50mm gun tub and a Navy sailor stood watch there full time at sea. One of these Navy sailors was a Kentucky guy and from the time we left dock until we returned, he was very seasick. I could hear him dry heaving all night. I sure felt sorry for him. He was never replaced. I often wondered how those supplies got to Australia in the first place. Such huge amounts and Australia was not that industrialized. We would head north through the Great Barrier Reef in small convoys and come back empty and alone. An empty ship in rough seas is really something. Pretend you’re a bug in a sealed bottle and on one of those white water rivers! You get the picture. On one of those return trips we were being escorted part way by a small military plane when it suddenly dropped into the water. We circled for quite awhile looking for the pilot (I think there were 2 crewmen), but nothing ever surfaced. I don’t remember if it was on this return trip or another one that stirred us up again. It was a dark night around 10 pm that suddenly the night was made bright as day. Someone on another ship had fired a couple of signal flares and they were floating above us. You can bet everyone except those on watch was on deck and expecting the worst. Then a distant ship signaled us to identify ourselves by signaling back a certain word from a page of a codebook. Well, our signalman (also radio operator) could not be found. That ship kept repeating its request. Finally locating our man, the answer was made. A Navy ship then came alongside and someone there on a bullhorn informed us that we were very lucky. As we went our separate ways I realized how suddenly things could happen. I guess that was a U.S. destroyer out prowling the seas in pitch black darkness looking for the sub or subs that was giving us fits (the subs surface at night to recharge their equipment). You can appreciate how very dangerous it was to sail in total darkness.

We were always glad to get into the reef and safety from subs. Each convoy going north would get attacked by a sub. Nearly every convoy would lose a ship. I remember the S.S. Port Morsby. She was the sister ship to the Colorado. Identical in every way. She was right across from us in the next line of ships and carrying the same cargo as we were. Those of us on deck at that time (it was nearly sundown) saw the huge explosion and fireball that went skyward. The ship disappeared just like that. A Navy LST (Landing Ship Transport – larger than a barge that landed troops on shore) also got hit and sank. In no time, the black smoke was way behind us on the horizon. About 80 crew members and 25 on the LST went just like that. There’s no answer to why it was them and not us. A decision of the sub captain. Or?? Another time we got into the shallows of the reef and wound up on a sandbar – stuck there ‘til tugs from the nearest port freed us. In the meantime, we suffered from hoards of mosquitoes. No one on the ship slept a wink. Then there was the time while unloading at Salamoa, New Guinea, a Lightening Pursuit twin-tailed fighter plane, crashed and burned on a hillside about a mile away. We went there and gathered small pieces of aluminum and short lengths of the plane’s machine gun ammo (35mm or 50cal). We took the live rounds to our engine room and pulled off the bullets and dumped the powder and fired off the cap and re-assembled the shells. I still have 3 of them, including a tracer round.

An Oiler’s duty was to keep all equipment in the engine room in operating condition. As the name suggests, all pumps, engines, controls, etc. had to be lubricated and maintained, steam glands tightened and (in port) repaired. Each Oiler had his squirt can (the kind that has a spout and a flat bottom that your thumb presses). We would polish the bottom with emery paper until it was paper thin and very touchy. We could squirt a shot of oil 30 feet easily. Well, the 3 cylinder reciprocating engine stood about 3 floors high, the cranks rotated at about a 4 foot diameter circle, all in the open. The piston rods, bearings, crank shaft parts – all had to be oiled every hour in operation. The Oiler would hold on to a rail and lean into the engine and reach into the bearings to make sure no black burnt oil showed. Then with his trusty squirt can, squirt oil into moving parts as they whizzed by. This had to be done no matter how rough the seas. One moment the engine is hovering above you and the next moment you are on top of it. I shudder at the times when I think of those hot oil slick hand rails and rough seas. How easy it was to slip – squashed like a bug by the revolving cranks.

I would like to take a little time to blow my own horn a little. I became proficient with the machinery. Replacing steam packing glands, remaking Babbitt bearings, and doing repair as required became natural to me. One time I came to the Third Assistant’s aid in adding water to a boiler, which had to be done by a steam injector. This is a unit of pipes that allows a jet of steam to flow across an orifice and “suck” water through a pipe into the boiler. The steam had to flow at the correct velocity. He wasn’t getting the right flow. He thanked me over and over for doing it. The Third Assistant (I can’t remember his name) was a nervous wreck from the beginning of the trip. He lost his voice and never regained it the entire trip and just used a loud hoarse whisper to converse. He begged me to transfer to his 8 to 12 watch, but I wouldn’t do it. To this day I am sorry for not doing it. I could have helped him regain his self-confidence and his voice.

The Second Assistant was a boozer. He would stock up a full supply of beer, etc. at the Officers Club in Sydney (only available to officers). Out at sea, we would get off watch at 4am and go to the crew’s mess room. There, he and his cronies would play poker and I would stay and watch. I was his errand boy. He would say, “John, go snare me a gopher.” I would go to his cabin (top deck of ship), get a quart bottle of beer, tie a cord to the neck, take it below to the refrigerator hold and put it into the brine tank for the maximum time of 6 minutes. It was then ice cold. At 7 minutes the bottle would crack – you can bet I was very careful after this happened once – and go back to the poker party. The guys would give me a tip out of every pot. I didn’t do too badly!

As you can guess, the Second and I became close friends. As I think back to the time he chewed me out for not knowing how to fill a boiler with water, I also think of how I saved his (A–) neck, by really sticking mine way out. We had finished being loaded up and ready for orders to sail. I was on watch and the order came from the Bridge to leave in a half hour. Now, that is the time it takes to warm up the engine. So, since it was the Oiler’s duty to go and awaken or alert the next crew for their watch, I would rush up 7 flights of stairs to call the Second. He was out like a light because he was boozed up – just muttering. Back down. I told the Fireman to start getting steam up. I started turning on engine valves, purging moisture from the cylinders, then back up to get the Second Assistant – and no luck. I go back down and start slowly turning the engine over; then back up and really shaking the Second. Back down – now the telegraph rings a command. I answer it and start the engine. The telegraph is a brass circular plate marked in segments (commands) with a handle that pivots around it. The Bridge and Engine room have their units connected together. As the Bridge moves the handle to a segment (command), the Engineer responds similarly. The Bridge sent down commands: slow ahead – STOP – slow astern – STOP – half ahead – full ahead. All of those commands were executed. Then stop and secure the engine, finished the operation, and we were at anchor out in the harbor waiting for a convoy. A short time later the Second Assistant came down and asked where we were. “At anchor,” I said. “How’d we get here?” “I did it – I couldn’t get you awake.” He never said one more word. He knew he could have lost his license and I had no authority to operate a ship engine. It was illegal and now about 60 years later I wonder where I got the nerve to do that. It wasn’t a motorboat. The engine, as large as a house, had tremendous power. What if it had stuck on full speed? The ship, going in circles or slamming into a pier is okay on television, but not funny to think about. Another time I nearly got into trouble by over-stepping my limit and it was that Evaporator again. I can’t remember why we had to operate it. I was checking it out and realized it was dangerously hot! I immediately opened a valve to exhaust it to the atmosphere – this being on the top deck near the boiler pop off valve. This opened valve, being almost as loud as the pop off valve, caused the Chief Engineer to again rush to the engine room. After checking, he found out that we were in shallow water and as a result, sediment had been entering the unit. Yes, it could have blown.

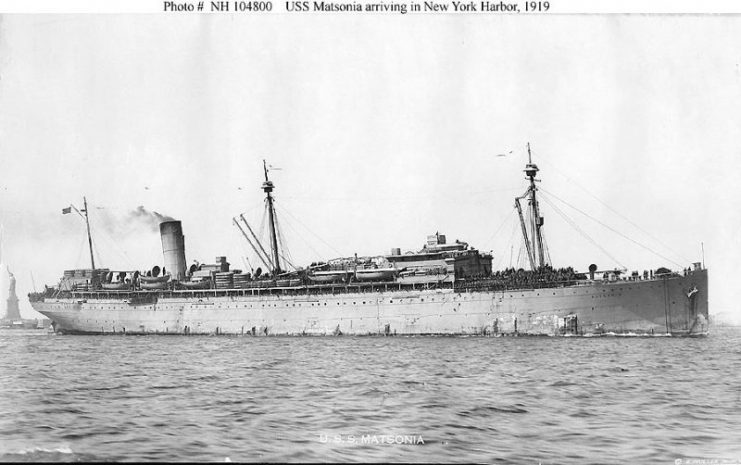

I started writing this story and am surely getting wound up – so many things I could say, but I’ve got to stop somewhere. A Merchant Marine crew signs articles for a trip, in our case, a year. This was the time to re-sign or payoff. All except 2 guys elected to go home. Just like other activities, we gathered our personal stuff and quietly left the ship, got on a train and to Brisbane where the troop ship S.S. Matsonia (a former luxury liner) would take us to San Francisco. It was loaded with returning service people including many pregnant nurses. I guess they were over zealous in their care for the wounded. It was quicker from Brisbane to San Francisco than it was from ‘Frisco to New York by rail.

Back home it again was a cold winter from the heat of Australia. In later years I would think back. What if I had stayed on the Colorado? I am positive I could have gotten an Engineer’s license. I would have been an Officer on the ship and staying in Australia. Or, could have been sunk the next trip! My life would not have been what it is – my family not existent. Ah, destiny! At any rate, I visited home for a short time and then on to New York and Philadelphia for another ship. I never had any leave coming. Sea duty was constant. Each time my tour ended and I left a ship, draft greeting were sent to me to report for induction. I simply reported to a seamen’s hall and registered for the next available ship.

After Australia, I made 6 trips across the Atlantic on Liberty ships (same type of ship before, but now larger and more modern) to France, England, and Mediterranean with all kinds of cargo – mainly food rations and of course, always bombs and ammunition. Also, I encountered all sorts of crew members – Engineers that were Horses A’s and also good guys. I reunited with Maurice Williams and we sailed together (he was the Fireman on the same watch with me. Our escapades, some really classics, could fill a book, so we’ll leave them out of this.

The Atlantic was always rough. I dreaded the return empty run because the ships bobbed around like corks. Those Liberty ships did stand a lot of punishment. The bunks always lay left to right – not front to back (not seamen’s words). As the ship would roll, I would waken up standing on my head, waiting for the longest time for it to roll the other way and I’d be standing on my feet. What a way to try to sleep. We never even took our clothes off and we didn’t dare bathe as we kept our life preserver always handy. Eating was a chore as we chased our utensils up and down the table. Sitting on the pot was done as fast as possible (no reading magazines), you’d hang on to hand rails and the water in the commode would slap you on your butt as the ship rolled. Fun!

The convoys were getting bigger. Newer Victory ships were replacing the Liberty ships. They had turbine engines that were much improved over the reciprocating engines I was familiar with. However, I never had a chance to sail on one of them.

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland covered many square miles of the Atlantic. Most convoys went through them to avoid the subs. On one trip, we came out of the fog and not a ship in sight (we were expecting to be in the convoy). Boy – a feast for a sub. Maybe the subs were tailing the convoy. Anyhow, we got to England on our own. As it were, the submarine threat there was subsiding. My last trips were in convoys of 200 ships (unbelievable!). This time we joined the thousands (true) of ships in the English Channel preparing for the Normandy invasion. When the invasion happened, we waited our turn and were unloaded partly at Omaha Beach’s temporary docks and onto ducks (those amphibious vehicles) – then a fast dash back to the States for another load. The next time back, all the ships were gone. We could go ashore at Cherbourgh and view the abandoned German fortifications. I had a lot of stuff for souvenirs, but all was confiscated by the Customs in New York. Soon afterwards the war in Europe was over.

The troops were being sent to the Pacific to bring that to a close. Then these men and women were being discharged and were returning home. Again, no big fanfare or bands present. As they left for war, they returned the same way – quietly taking up where they left off, getting a job, getting married, raising families, and gradually getting older. I worked odd jobs like highway construction, railroad gang, and factories in the area (EKCO, RCA, NCR).

Finally, after 60 years, a memorial is being built for them in Washington D.C. Very few will be around to see it. Instead, to their dismay, their children and grandchildren no longer view honor, duty, and patriotism as virtues to defend, with the crowning insult being the election of a draft dodger for our President.

As quietly as they went to war and as quietly as they returned, so also quietly they are leaving the scene with their individual memories of a terrible time. This relentless time is finally giving them peace. The restless oceans and the skies above leave no marked trails and the land has healed, its scars leaving little to show where they, the uncommon, trod performing a task that was thrust upon them. The rest is history.

Author: John Sekel

DOB: 7/17/21

DOD: 5/6/2013

Service Date: Merchant Marines, 1943 – 1945

Awards: Atlantic War Zone Bar, Pacific War Zone Bar, Mediterranean War Zone Bar