War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

During the mid- 1950s, while Eric Hinrichs was a fifth-grade student in elementary school in St. Louis, his teacher shared an admonition of the Cold War that cemented itself in his thoughts—“study your math and engineering or else the Russians will roll right over our country.” As he gained a little age and embarked upon his adult life, her words helped inspire a life of service dedicated to protecting the United States against foreign threats.

Graduating from Roosevelt High School in St. Louis in 1961, Hinrichs briefly attended classes at Washington University before transferring to the University of Missouri-Columbia. During his course of study at the university, he participated in the Army Reserve Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC) program.

“I chose to pursue an electrical engineering degree because at the time I realized it was probably the highest paying career for a single graduate degree, and it was highly marketable as well,” he said. “I graduated in 1968 and received my commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army at the same time,” he added.

At the time, Hinrichs explained, he was able to speak three languages and was accepted into the military intelligence branch of the Army. He was then sent to Ft. Benning, Georgia to undergo further training in preparation for deployment to Vietnam; however, a fortuitous conversation with his colonel changed the trajectory of his military career.

“My colonel said that since I had a German last name, he wondered if I could speak German,” Hinrichs said. “I didn’t bother to tell him that it was more Dutch than German, but instead recited a poem that I had learned while taking German in high school.”

As Hinrichs noted, whether or not he accurately recited the poem was irrelevant because it so impressed the colonel, he affirmed such language skills would be of more benefit to the U.S. Army in Germany rather than Vietnam. Hinrichs mirthfully remarked, “That really became an unexpected break for me!”

The soldier was soon on his way to Germany where he began his first assignment at the IG Farben Building in Frankfurt, which, he said, was at one time the largest office-building complex in Europe and oftentimes referred to informally as the “Pentagon of Europe.”

“My assignment was with the Army Security Agency, Europe (ASAE), and the IG Farben building was used to house a number of intelligence agencies,” Hinrichs explained. “The ASAE was established after World War II to provide signal intelligence and communications security support to U.S. Forces, Europe and its subordinate commands.”

During his tenure in Germany, Hinrichs recalled, he and his fellow soldiers were introduced to the realm of signals intelligence (SIGINT), which included exposure to Ampex reel-to-reel recorders crammed into several rooms in their facility and used to store various types of classified information.

“Some of the people that I worked with were sent to the Army Security Agency field station at Tempelhof in Berlin and others to the station at Augsburg—the site of a Wullenweber AN/FLR-9 radio direction finder established during the Cold War.”

Hinrichs went on to describe from the viewpoint of an engineer that the Wullenweber was a “type of Circularly Disposed Antenna array used for radio direction finding to triangulate radio signals for radio navigation, intelligence gathering and search and rescue.”

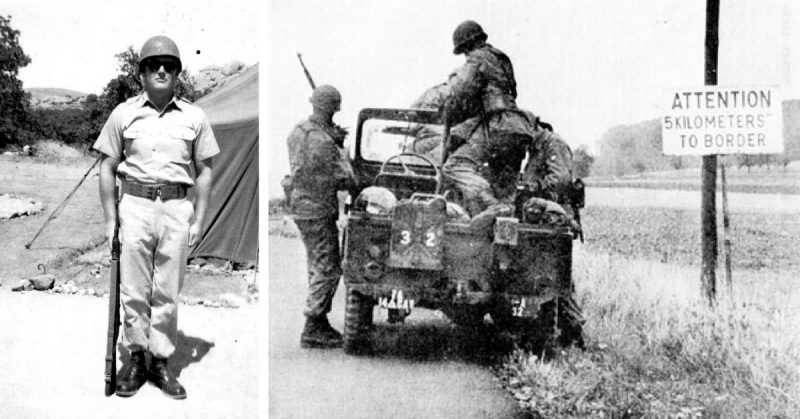

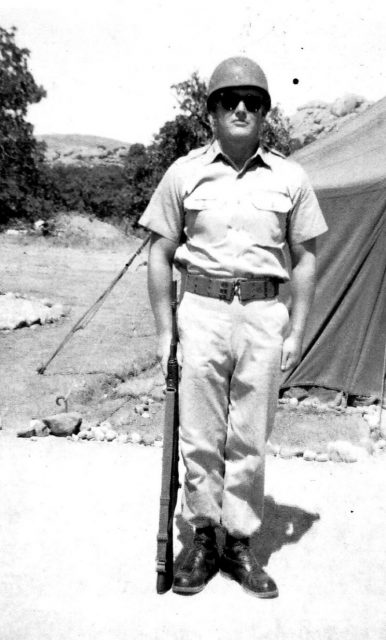

While an assortment of emerging and sophisticated technologies were employed to combat the Soviet threat, Hinrichs embraced what he characterized as a “prestigious opportunity for a young officer” when he was sent to Anzio, Italy to provide electronic warfare training to senior NATO officers.

“It was one of those situations where I was there with the right set of skills at the right time,” Hinrichs said. “I even had the Norwegian Minister of Defense in one of my courses and that was certainly quite an experience for a second lieutenant,” he added.

In 1970, Hinrichs’ two-year military commitment ended and he made the decision to return to Missouri. In the years that followed, he was employed for two years with the Federal Communications Commission but, as he pointedly affirmed, “I always wanted to get back to Europe.”

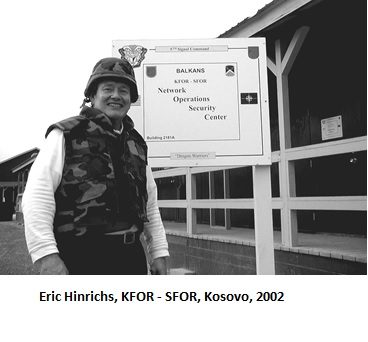

He achieved this desire in 1973 when he traveled to Worms, Germany to serve as a civilian engineer with the 5th Signal Command, helping modernize Army airfields by installing equipment such as satellite systems. Throughout the next several decades, he worked in a number of technologically driven capacities in both the U.S. and Europe.

In 1989, while employed at the main headquarters of the Defense Communications Agency in Stuttgart, Germany, he witnessed an event that became symbolic of the end of the Cold War—the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Continuing to “work and retire” several times in the last few years, he remains active “physically, mentally and spiritually,” and enjoys teaching four European languages at the college level. While reflecting on his experiences during many stages of the Cold War, Hinrichs affirms his story helps demonstrate the resolve that helped the U.S. prevail in this unique conflict.

“When I first went to Germany as an Army officer in 1968, that was a month after the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia—and everyone I worked with understood the significance of the threat that our country faced,” Hinrichs said.

“For years, I have worked with people who believed in their jobs, had a great sense of purpose and were dedicated to stopping the Soviet threat.” He added, “And when the Berlin Wall fell, we truly understood the symbolism of that event—it represented that we had won the Cold War through our desire to prevail and it gave us a great sense of accomplishment.”