By Guest Blogger David D. Kindy

Robert Lee Scott Jr.,World War II flying ace and author of “God is My Co-Pilot” is best remembered as the flamboyant combat leader of the Flying Tigers. After the war, he enthralled generations of potential pilots with his exploits and daring in the air over China and his record of 10 air-to-air kills. Or 13 victories. Or even 22 Japanese aircraft shot down.

The thing is, Scott was not the squadron leader of the Flying Tigers. He actually was commander of the 23rd Fighter Group, the U.S. Army Air Force unit that replaced the legendary volunteer air wing that helped the Chinese take on the Japanese juggernaut in the early days of the war.

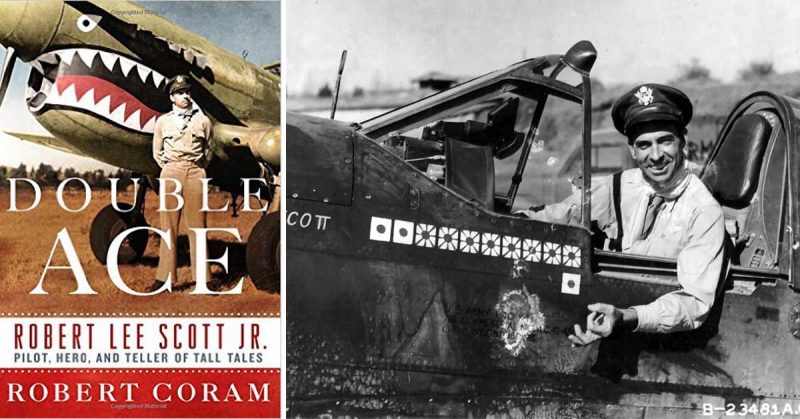

But that was Scott. The enigmatic, colorful and often frustrating character blazed a path across the sky and into America’s heart with his larger-than-life recollections of his experiences and his devil-be-damned attitude. “Double Ace: Robert Lee Scott Jr., Pilot, Hero, and Teller of Tall Tales” by Robert Coram is a lively and exciting account of a remarkable man who led an incredible life. At least the parts that can be verified, that is.

As Coram cleverly points out, Scott was a Southern boy who learned early the lesson that a good story can always be made better. In the honored good-old-boy tradition of country campfire tales made grander, this Georgia son of an overly ambitious mother knew how to enthrall audiences with his often embellished exploits. Why let a few unimportant details get in the way?

Scott was pushed to be a famous pilot by his mother almost from the start. She had big plans for her oldest son and seemed to realize that the new field of aviation was the place that he would excel. Born in 1908, Scott grew up in the era when airplanes were just beginning to soar – literally – into the American consciousness. His sheer determination and guts pushed himself higher and further as he streaked across the sky with his beloved planes.

When the United States entered the war, Scott was on the outside looking in. At 33, he was considered too old to be a fighter pilot and seemed destined to remain stateside as a trainer, helping prepare 20-somethings for air combat. But through his own perseverance and uncanny good luck – which seemed to stick with him much of his life – Scott ended up in the China-Burma-India theater of operations and was able to convince Claire Chennault – father of modern tactical combat aviation and founder of the Flying Tigers – to give him a chance.

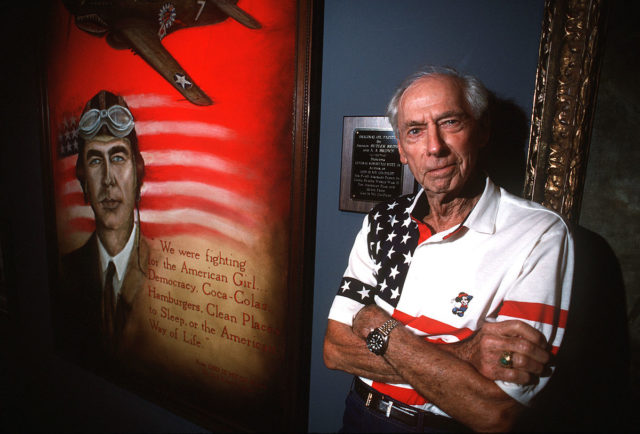

Scott quickly proved himself and the rest – as they say – is history. He went on to become a double ace, credited with 13 kills (later amended to 10 by the Air Force) with another nine probables. He took over as squadron commander when the American volunteers of the Flying Tigers were absorbed into the Army Air Force and made headlines across the United States for defeating the Japanese at a time when many other U.S. units were suffering horrible losses.

When Scott returned home in 1944, he was propelled to further fame by “God is My Co-Pilot,” which he wrote – actually, dictated – in three days. The book and subsequent movie would inspire future generations of young men to become pilots. It is still in print today.

Scott’s retirement years were filled with nearly as much excitement and intrigue as his war service. He would continue to write books, mostly about his war ordeals – many of which seemed embellished or at least unverifiable – but also about his experiences as a big-game hunter. And he became a successful speaker, touring the country and enthralling audiences with his war stories. He would fulfill a lifelong dream by walking the Great Wall of China. Well, he said he did. There was no one else there to say he didn’t. Scott eventually settled back in Georgia and helped build a major aviation museum in Warner Robins, a tiny town within spitting distance of his hometown of Macon.

Coram, a Georgia boy himself, uses humor and wit to tell Scott’s story. Throughout much of his life, the aviator was often blustering – “bugling,” they call it in the Army – his way through his many adventures and mishaps. When in doubt, come up with the best story you can think of and let it fly. More often than not, as in Scott’s case, it soared.

As Coram aptly points out, Southern culture is filled with legend. History is necessary but it’s really the telling of the story that’s the crucial thing. It’s better to hold your audience by spinning a good tale than losing them with the details of facts. That’s not to say that Robert Lee Scott was not a war hero, courageous, fearless or successful – he was all of those things and more. It’s just that, well, you gotta tell a good story.