War History Online presents this Guest Article from Peter B. Gemma

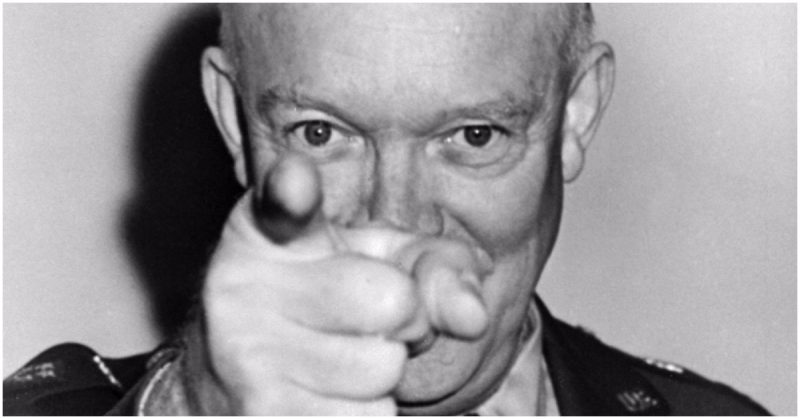

General Dwight David Eisenhower is best remembered as the military leader who led allied forces in Europe to victory in World War II. According to Pulitzer-Prize winning historian T. Harry Williams, the popular view of General Eisenhower’s military career was as, “the friendly, folksy, easy going soldier who reflects the ideals of a democratic and industrial civilization and who cooperates easily with his civilian superiors.”(1)

His successful 1952 and 1956 presidential campaigns – run with the amiable moniker of “I Like Ike” – gave him a populist, grandfatherly political image. The New York Times obituary for Eisenhower asserts:

[He] was not a dashing battlefield general nor a masterly military tactician,

[but] as President he governed effectively through the sheer force of his popularity among average Americans of both major parties … (2)

It is hard to find critical assessments of Eisenhower as a military leader or as a politician. Plaudits such as “confident,” “brilliant,” and “a hero of our time, the real thing, the soldier of democracy” quickly appear when researching his name on the Internet. Eisenhower biographer Stephen Ambrose, who penned no fewer than five books about his subject, concedes that Eisenhower, “proved to be outstanding at public relations” and that, “Eisenhower manipulated the press for his own purposes … he was more aware of the importance of the press, and better at using it, than any other public figure of his day.”(3)

That skill is still evident on-line.

There is seepage of revisionist views of Eisenhower’s public persona however, some of which can even be ferreted out of the many favorable biographies, but they only bubble up here and there for the methodical armchair historian. These alternative opinions of Eisenhower reveal the lesser-known facts about how much of his military success was due to political machinations.

“Shot out of a cannon”

After graduating from West Point (61 out of 164 in his class), Eisenhower’s good fortune began early in his military training when he attended the Army’s Command and General Staff School in 1925. Military historian Robert Bateman maintains that Eisenhower, “had a minor advantage over his peers: he had [George S.] Patton’s complete notebook … Now that alone is not enough to prove anything,” Bateman observes, but “conceivably Eisenhower, a man whose grades placed him only among the top third of his class at West Point, could have developed a sudden academic flair … still, somehow the plodding student of 1915 became the number one graduate in the same rote-memorization program he found so stultifying” at West Point.(4)

It took 20 years for Eisenhower to rise from the rank of First Lieutenant to Lieutenant Colonel(5), and he spent 16 years in miscellaneous administrative duties that included recruitment, staff work, and as a football coach.

In 1935, Eisenhower was assigned to the Philippines where he served as a military adviser to the Manila government and as chief military aide to General Douglas MacArthur. It was from here that his meteoric rise to power took off. Journalist Marquis Childs notes that Eisenhower “became a friend of President Manuel Quezon and during his frequent weekends on the presidential yacht, his skill at bridge and poker stood him in great stead.” (6)

Upon leaving Manila, President Quezon awarded Eisenhower the Distinguished Service Cross of the Philippines. Eisenhower’s charm and his keen eye for social opportunities served him well. “He developed a political awareness and a thorough understanding of what it took to survive in the higher reaches of the military and political jungle of the 1930s,” according to Carlo D’Este.(7)

Marquis Childs, author of Eisenhower: Captive Hero, writes that Eisenhower was seemingly, “shot out of a cannon from complete obscurity to a position at the very top, where he spoke as an equal with kings and prime ministers and presidents.”(8)

In politics, as President Franklin Roosevelt often said, there are no accidents. Eisenhower’s relationship with General MacArthur was a pivotal point for his astonishing rise to power. However, Eisenhower’s insolence for MacArthur is recorded in his 1954 diary: “I just can’t understand how such a damn fool could have gotten to be a general.”(9)

In December of 1939, Eisenhower left the Philippines as a Lieutenant Colonel. This is a good place to step back and review a timeline for his military career:

- In late 1940, Eisenhower was appointed Chief of Staff of the Third Military Division; four months later he was promoted to Colonel and made Chief of Staff of the Ninth Army Corps. In June of 1941 he was appointed to Chief of Staff of the U.S. Third Army and by September he was a Brigadier General.

- On February 16 1942, he was made Assistant Chief of Staff of the War Plans Division. In June of that year, Eisenhower was given command of the European Theater of Operations. By then he was dining with Winston Churchill twice a week.

- In July 1942, he was awarded three stars of a Lieutenant General, and in February of 1943 – three years from the time he was a Colonel – Eisenhower became a full General.

Ten months later, although he had never commanded troops on a battlefield or experienced warfare firsthand, he was appointed Supreme Allied Commander in the European Theater of Operations.

It was in late 1941 that Eisenhower was brought to the attention and direction of General George Marshall (one observation of their relationship reads, “General Dwight Eisenhower was the closest any soldier ever came to being George Marshall’s protégé.”)(10)

Eisenhower’s association with Marshall opened many doors including one to the White House. Just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower accompanied Marshall who had been summoned to Washington to meet with President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Author D’Este again emphasizes that, “with Eisenhower, it was all about relationships and none was more important than his association with Winston Churchill.”(11)

Marshall promoted Eisenhower – ahead of 366 senior officers – and sent him to London. Although he had barely heard of Eisenhower six months earlier, and Eisenhower had never served in battle, Marshall gave Prime Minister Churchill the files of three officers, including Eisenhower’s, to consider for heading-up American military operations in Europe. According to Marquis Childs, “Churchill is reported to have felt that Eisenhower would be more cooperative and even more susceptible to Churchill’s powers of persuasion than the other two generals.”(12)

Writer Tom Carson observes that, “The myth that Eisenhower was plucked from obscurity by Chief of Staff George C. Marshall for high command after Pearl Harbor is only true insofar as he was unknown to the public.” Carson asserts that Eisenhower had been:

A cagy Army careerist ever since West Point, cultivating higher-ups in a position to finagle plum assignments for him and making himself indispensable to both John J. Pershing (his World War I predecessor) and Douglas MacArthur (his World War II Pacific doppelgänger). No wonder George S. Patton’s nickname for him was ‘Divine Destiny.(13)

Upon his arrival in England, Eisenhower was charged with communicating war news to an anxious America. He had an intuitive sense for his public relations responsibilities, then and in his future political endeavors. Eisenhower recruited media and publicity impresario Harry Butcher, head of the CBS operations in Washington, DC, to be a member of his inner circle. Butcher later recounted, “When we talk of public relations, I have a feeling that I will gain a reputation as an expert in this field. I’ll be getting the credit for Eisenhower’s good sense, for he is the keenest in dealing with the press I’ve ever seen, and I have met a lot of them.”(14)

Another member of General Eisenhower’s inner circle was Kay Summersby, who was an ambulance driver for the British Mechanized Transit Corps until she was assigned as Eisenhower’s driver when he arrived in London. She quickly became his personal secretary, serving until November 1945. In her book, Past Forgetting my Love Affair with Dwight D. Eisenhower, she wrote of Eisenhower’s political savvy during the war:

Churchill’s fondness for the American commander was best revealed at the dinner parties. Although Eisenhower normally was the lowest-ranking general present and in spite of the rigid protocol which rules Government and military circles in England, the P.M. invariably placed Gen. Eisenhower in the highest chair of honor, to his immediate right.(15)

On the front lines

There are varying assessments of General Eisenhower’s command of allied forces during the war – most are highly favorable. Many historians credit him with keeping the diverse Allied leadership united in spite of a wide range of egos and professional competence. For this writer, an assessment of Eisenhower’s combat tactics is best left to expert military strategists. However, consideration should be given to those historians and military leaders who have reservations about General Eisenhower’s role as Supreme Allied Commander.

In their book Masters at the Art of Command, Martin Blumenson and James L. Stokesbury write, “A surprising number of professional soldiers and military historians give General Dwight D. Eisenhower failing grades as a commander in World War II.”(16)

A frustrated British Field Marshall Lord Alanbrooke, Chairman of the British Chiefs of Staff Committees, once fumed that, “Eisenhower, though supposed to be running the land battle, is on the golf links at Rheims – entirely detached and taking practically no part in the running of the war.” Alanbrooke asserted that Eisenhower was:

At a loss as to what to do, and allowed himself to be absorbed in the political situation at the expense of the tactical. I had little confidence in his having the ability to handle the military situation.(17)

British Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, Commanding General of the Allied Ground Forces in Normandy, complained that Eisenhower, “had not the experience, the knowledge, the organization, or the time … he was out of his depth and in trying to do this he neglected his real job on the highest level.”(18)

Montgomery and Alanbrooke were not alone:

- General of the Army Omar Bradley believed Eisenhower, “had little grasp of sound battlefield tactics.”(19)

- Admiral John Hall, the commander of Amphibious Force ‘O’, which landed the 1st Division at Omaha Beach, wrote that Eisenhower, “was one of the most overrated men in military history.”(19)

- “It appears to me that Eisenhower is acting a part,” General George S. Patton opined, “He is nothing but a Popinjay – a stuffed doll.”(20)

After the Normandy invasion, when it came to adopting a “broad front” strategy to bleed the Germans dry or seizing on the British plan of focusing on a direct path to Berlin, Montgomery said that Eisenhower played the politician when it came to decisive military action: “He had no plan of his own … Eisenhower held conferences to collect ideas; I held conferences to issue orders.”(21)

Eisenhower often mixed political angles into his military strategies. As biographer Jean Edward Smith notes: “Without seeking the approval of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, the British war cabinet, or Washington, he had installed a new government in France … he outmaneuvered FDR and the State Department so skillfully that he left no fingerprints … Ike moved by subtlety and indirection. His amiable personality and avuncular enthusiasm concealed a calculating political instinct that had been honed to perfection.”(22)

John Stuart Mill once wrote, “Popular opinions are often true, but seldom or never the whole truth.” A life size General Dwight Eisenhower, scaled down from icon to a man of distinction – albeit one possessed by a relentless ambition for rank, fame, and power – is necessary inasmuch as real people make history.

Peter B. Gemma, an award-winning freelance writer, has been published in a variety of venues including USA Today, Military History, the DailyCaller.com,

The Washington Examiner, Op/EdNews.com, and AmericanThinker.com.

Footnotes:

1. Carlo D’Este, “Dwight D. Eisenhower: Douglas MacArthur’s Aide in the 1930s,” Military History Quarterly Winter 2003.

2. March 29, 1969.

3. Eisenhower: Soldier and President; Simon & Schuster; 1991.

4. “U.S. Army Officers Between World Wars I and II Often Placed Personal Ambition Above Honor,”Military History, June 2004

5. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_career_of_Dwight_D._Eisenhower

6. Eisenhower: Captive Hero, Marquis Childs; Harcourt Brace, 1958

7. Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life; Henry Holt, 2002.

8. Ibid, Eisenhower: Captive Hero.

9. Ibid, Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life.

10. “Eisenhower,” at National Portrait Gallery website: www.npg.si.edu/exh/marshall/meisen.htm.

11. Ibid, Eisenhower: A Soldier’s Life.

12. Ibid, Eisenhower: Captive Hero.

13. “The Republican Socialist,” American Prospect, March 9, 2012, http://prospect.org/article/republican-socialist

14. My Three Years With Eisenhower: The Personal Diary of Captain Harry C. Butcher, USNR, Naval Aide to General Eisenhower, 1942 to 1945; Simon and Schuster, 1946

15. Simon & Schuster, 1976. In the book, Sommersby revealed her affair with Eisenhower: “I suppose inevitably, we found ourselves in each others’ arms in an unrestrained embrace. Our jackets came off. Buttons were unbuttoned. It was as if we were frantic, and we were.”

16. Masters at the Art of Command; Houghton Mifflin, 1975.

17. Alanbrooke War Diaries 1939-1945, Alex Danchev editor; Widenfeld & Nicolson, 2001.

18. Carlo D’Este, “A Lingering Controversy: Eisenhower’s ‘Broad Front’ Strategy,” Armchair General, October 7, 2009.

19. The Patton Papers: 1940-1945, Martin Blumenson; Houghton Mifflin, 1974.

20. Brothers, Rivals, Victors: Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley and the Partnership that Drove the Allied Conquest in Europe, Jonathan W. Jordan; NAL Caliber, 2011.

21. Ibid, “A Lingering Controversy: Eisenhower’s ‘Broad Front’ Strategy,” Armchair General.

22. Eisenhower: The Public Relations President; Lexington Books, 2014.