War History Online presents this Guest Article by Thomas D. Pilsch

With great solemnity and reverence, America observed the 75th anniversary of the devastating December 7th, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor that thrust the nation into World War II. There was little recognition, however, of the anniversary of a second highly consequential attack on that strategic Pacific base by the Japanese Navy on March 4, 1942, less than three months later.

The story of the first attack on Pearl Harbor — President Roosevelt’s “date which will live in infamy” — is a familiar one. At 7:55 AM on a Sunday morning, over 350 Japanese planes launched in two waves from aircraft carriers north of Hawaii bombed the airfields and fleet anchorage on the island of Oahu.

The Japanese achieved complete surprise with results beyond their expectation. All eight of the battleships in the U.S. Pacific battle squadron were hit. Four of them were sunk with two, USS Arizona and USS Oklahoma, total losses. The island’s air defenses were devastated. The greatest loss of all was the 2,403 Americans – Army, Navy, Marines and civilians — who died in this attack.

Japan had won a stunning victory in this first attack. The raid had achieved its objective of disabling the US Pacific fleet to give Japan a free hand in its planned conquest of Southeast Asia and the East Indies. This, they thought, would allow the Empire to secure resources needed to establish preeminence in Asia and the Pacific. Tokyo reasoned that by the time the U.S. was able to rebuild its fleet, the Japanese position in the Pacific would be so secure that Washington would have no choice but to accept this fait accompli.

History ultimately was to prove Japan’s Pearl Harbor victory a pyrrhic one. Its leaders had not anticipated that an enraged America would dedicate itself to training retribution upon the home islands and would entertain no consideration of negotiation.

Second Thoughts

Early in 1942, Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) leaders began to have second thoughts about missed opportunities in the Pearl Harbor strike. By chance, the two Pearl-based aircraft carriers were delivering aircraft to U.S. island possessions and were untouched. More significant to America’s war effort in the Pacific was the value of the fuel supplies and undamaged shipyard, particularly the large dry docks. Without these, the damaged U.S. ships could not have been repaired and supported. The remaining fleet would have had to operate from the West Coast. With the facilities intact, pressure on the IJN might build sooner than desired.

Historians continue to debate the decision of the Japanese force commander, Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, not to launch an unplanned third wave to destroy the Pearl Harbor facilities in lieu of withdrawing to the north as he did. He had accomplished his objective of disabling the U.S. fleet and was uncertain of the location of the two U.S. aircraft carriers. A third wave would have necessitated a risky night recovery of the attack force. Most dangerous of all, Nagumo would have had to break radio silence to coordinate the refueling of his fleet for the changed plan.

With the IJN committed to its southwestern Pacific strategy, there were few viable options to revisit Hawaii in early 1942. Nevertheless, the IJN general staff approved a plan for a small reconnaissance and bombing raid against the highest value target, the large dry docks in the Pearl Harbor shipyard.

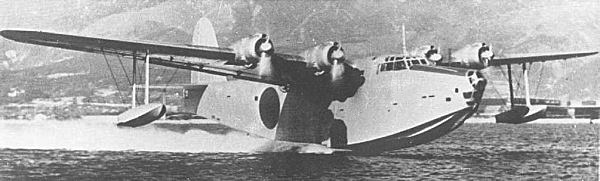

The raid would be conducted by a new, long-range flying boat patrol bomber, the Kawanishi H8K (Allied reporting name Emily). First flown in early 1941, the aircraft was just completing development a year later, and only the two prototypes were available for a second Pearl Harbor attack, coded named Operation K.

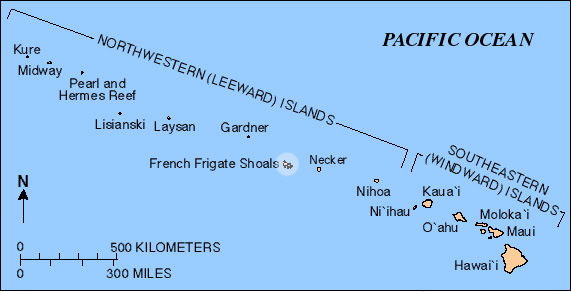

The Emilys would require refueling to fly from a forward Japanese base to Oahu. This refueling would be conducted from submarines in the sheltered waters of French Frigate Shoals, an uninhabited atoll 500 miles northwest of Pearl Harbor.

Irony

While Japan had experimented with refueling of seaplanes from submarines, there is a strong belief that the details of Operation K were suggested in a novella serialized in The Saturday Evening Post in 1941. Written by then-Navy Reserve intelligence officer Lieutenant Wilfred Jay Holmes in 1940 under the nom de plume Alec Hudson, the manuscript was eventually cleared by Naval Intelligence, and the story “Rendezvous” was published as two installments in August 1941.

In Holmes’ fictional account, U.S. Navy PBY Catalina flying boats attacked an “enemy” in the Western Pacific after refueling from submarines at an uninhabited atoll 1,000 miles from the target. The similarity to the Operation K plan is undeniable.

Fog of War

The IJN deployed four large I-class submarines to support the operation. Two were to enter French Frigate Shoals to refuel the Emilys. A third was to stand offshore as a backup and to guard the approach to the anchorage. The fourth submarine was to patrol just south of Pearl to provide weather reports and rescue support if needed, but it disappeared without trace en route to its patrol point and never provided weather information.

On the morning of March 3, 1942, the two Emilys departed Wotje Atoll in the Marshall Islands and landed at the rendezvous point at dusk. Refueling went without incident, and the pair of flying boats made a moonlit takeoff for Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese aircraft were detected by radar 200 miles from Oahu. U.S. commanders declared an air raid alert and launched fighters, but the lack of airborne and ground controlled intercept radars prevented contact.

As the two Japanese attackers flew over Oahu from the north just before 2 A.M. on the 4th, they encountered a heavy rain shower with dense clouds obscuring the south end of the island. The lead pilot thought he sighted Ford Island in the center of Pearl Harbor and set up a bombing run on the dry docks just to the south. The clouds again covered the target, so he dropped his bombs on timing from his Ford Island visual fix. His four 250 kilogram bombs impacted on a mountainside six miles east of Pearl Harbor.

The second airplane became separated from its leader during this maneuvering, and its pilot also dropped his bombs on an estimate of the target location. There is no record of these bombs having impacted, and it is assumed that they fell into the sea.

Both aircraft returned to the Marshall Islands without incident.

Unintended Consequences

Even without the intervention of bad weather, Operation K had a very low probability of being anything more than a nuisance raid. As the U.S. was to learn later during the bombing campaign in Europe, the ability to hit small targets from the air under combat conditions in daylight was more difficult in practice than in theory. Without a precision bombsight, with only eight small bombs and at night, the Japanese flyers had little chance of success.

But like the Doolittle bombing raid on Tokyo a month later, this second attack on Pearl Harbor was to have unintended consequence at Midway Island in June 1942.

On April 12, 1942, Lt. Col. James H. (Jimmy) Doolittle led a squadron of 16 B-25 bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet to carry the war to Japan and give a needed boost to flagging American morale during the dark early days of the war. In this latter objective, the raid was a complete success – American spirits soared. But this operation triggered an unexpected chain of events that ultimately sealed the fate of Japanese ambitions in the Pacific.

The Doolittle Raid alerted Japan’s leaders to the need to extend their defensive perimeter further east. Their focus shifted to an invasion of Midway Island and an effort to draw the American fleet into a decisive battle, but their plan was not to be. Through the work of code breakers, the availability of the Pearl Harbor dry docks, and Herculean efforts of shipyard workers in returning the carrier USS Yorktown – heavily damage in the Battle of the Coral Sea – to service in 48 hours, US Navy commanders were able to execute an audacious ambush and hand the IJN a stunning defeat at Midway June 4-7, 1942. Although the U.S. lost the carrier Yorktown, the four IJN carriers sunk by Navy pilots were a loss from which Japan never recovered. Midway was the turning point of the Pacific War.

The December 7th attack on Pearl Harbor had been a wakeup call for the American people. The second March 4th raid provided a similar jolt to the American military. U.S. commanders did not believe Japan had the capability to attack Pearl Harbor again except by aircraft carriers. Reminded of the “Rendezvous” article, however, they realized that Hawaii faced a previously unappreciated threat from seaplane attacks. U.S. Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester Nimitz ordered French Frigate Shoals and other islands suitable for refueling to be continuously patrolled to deny their use by the Japanese.

In preparation for the attack on Midway, the IJN had planned to use the Operation K scenario for a pre-invasion reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor to determine the status of the U.S. fleet. When the refueling submarines arrived at French Frigate Shoals on May 30th, they found the atoll guarded by U.S. patrol ships and were forced to withdraw. By the time the IJN was able to organize an alternate submarine picket line, the three U.S. carriers had slipped by to set their trap north of Midway.

By tipping their hand and revealing a valuable technical capability in the questionable March 4th attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese denied their fleet commander at Midway the intelligence that might have changed the outcome of that battle and perhaps the course (if not the outcome) of the Pacific War.

The lesson of this sidebar to history is that technological advantage is a fragile commodity. The potential gains from its first use in combat must be considered against the risk of its premature revelation to an opponent. Unfortunately, the reaction of an opponent to a wake-up call and its echoes, be they technical, tactical or strategic, can only be fully appreciated later — in the pages of history.

Thomas D. Pilsch is a retired Air Force officer who teaches and writes on the history of modern war. He lives in Bryan, TX.