War History Online Presents This Article By Guest Blogger Jack Hawkins

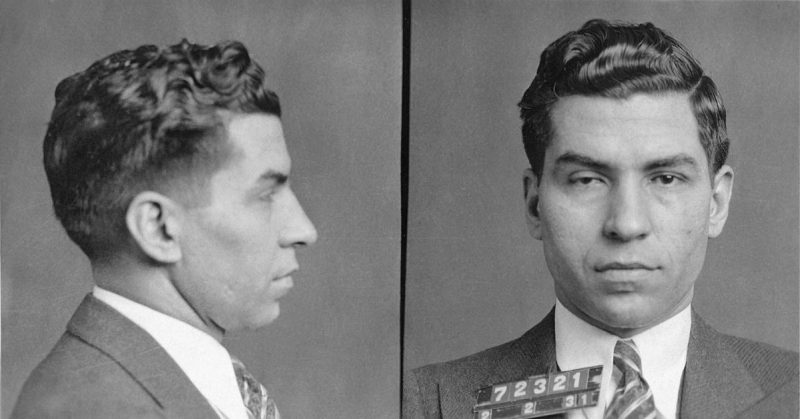

It is often said that crime does not pay, and when Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano was sentenced to 30-50 years for ‘compulsory prostitution’ on 18 July 1936, he may have considered such a sentiment.

However, as with many idioms and adages, there are exceptions to the rule that, typically, arise in exceptional circumstances.

The Second World War was the most exceptional circumstance of them all, and on December 7, 1941, the United States was plunged into it with the attack on Pearl Harbor. For Lucky Luciano, the national and governmental paranoia and anxiety that followed would be the ticket to his freedom.

By 1945, the war’s inauspicious start was largely forgotten for the United States had emerged as the greatest victor of the conflict. Its economy was strengthened, its power unprecedented and its cities unmarked, which was in stark contrast to their battered and bankrupt European allies who had not enjoyed the comfort of the Atlantic and Pacific barriers.

This last point, however, is not entirely fair, for while the American people did not suffer the massacres of the Eastern Front or even the bombing raids of the Blitz, their sailors certainly faced the terror of the Atlantic war, which the U-boats brought much closer to the American mainland than many may realize.

Between January and April 1942, 1.2 million tons of shipping was sunk off the eastern seaboard, which constituted approximately 46% of the 2.6 million tons of shipping that the Allies lost during this period.

Historian Michael Gannon described this naval onslaught as ‘America’s second Pearl Harbor,’ while the German commanders of the time named it the ‘happy time’ and ‘golden time,’ for they lost just three U-boats in January and two in February.

So dire was the situation that on 23 February 1942 President Roosevelt conceded: ‘We have most certainly suffered losses from Hitler’s U-boats in the Atlantic – and we shall suffer more of them before the turn of the tide.’

Indeed, the U-boat menace in North American waters persisted long after the tide had turned; during the German surrender in May 1945, several U-boats sailed up the Piscataqua River and capitulated to New Hampshire state police.

More sinister than this, however, was the mysterious fire aboard the SS Normandie on 9 February 1942. The French liner was being converted into a troopship in New York harbor when sparks from a welding torch ignited a pile of life jackets, which quickly spread across the wooden furnishings. The ship capsized later that evening.

Rumors of sabotage immediately circulated. Meyer Lansky and Luciano alleged in detail that it was a mob job carried out by Albert Anastasia with the intention of improving Luciano’s chances of release.

The government’s fear, however, was that it was the work of German spies. After all, it certainly wasn’t without precedent.

In April 1915, there was a spate of unexplained fires and explosions aboard Allied ships that had departed from New York. It was later revealed that German spy Franz von Rintelen had enlisted several longshoremen to plant explosives on ships docked across New York harbor.

With Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933 came renewed efforts to sabotage the United States from within. Indeed, using an invaluable insider named William G. Sebold, the FBI foiled the Duquesne spy ring, a 33-member team that constituted the largest single spy ring in American history.

Despite this success, US defense and especially New York naval intelligence had become anxious and even quite desperate about national security. Lieutenant Commander Charles Radcliffe Haffenden, responsible for the Third Naval District, said:

“I’ll talk to anybody, a priest, a bank manager, a gangster, the devil himself, if I can get the information I need. This is a war. American lives are at stake.”

It was in this panic that the government turned to the underworld, which Lucky Luciano was running from behind the bars of Clinton State Prison in upstate New York.

What landed him there was not ‘compulsory prostitution,’ that was merely the vehicle that special prosecutor Thomas Dewey used to nail him. Luciano was not merely a pimp, but the face and father of organized crime.

After orchestrating the murders of his boss Joe Masseria and rival Salvatore Maranzano, who were the biggest ‘Mustache Petes’ of the old school ‘Boss of Bosses’ hierarchy, Luciano established the Commission in 1931, which comprised the leadership of New York’s Five Families and the Chicago and Buffalo outfits.

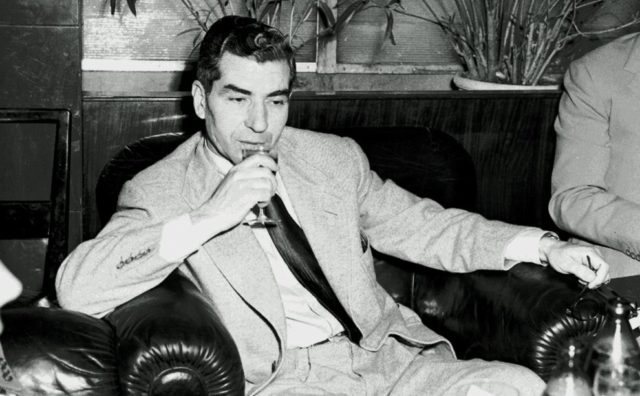

With an emphasis on corporate negotiation rather than wanton violence and a willingness to do business with mobsters of different races, Luciano and his associates reaped massive returns from their various ventures, which included prostitution, narcotics, loan-sharking, gambling and labor rackets.

In 1942, Luciano agreed to use his enviable influence to supply the government with intelligence from the harbor and also promised that no strikes would occur.

Ultimately, it was the latter that Luciano definitely delivered on, for the value of information Luciano’s men obtained from the harbor was, according to Thomas Dewey, ‘not clear.’

However, the effect Luciano’s negotiation had on the underworld and Italians back in the old country should not be overlooked. By making a deal with the government, Luciano made it acceptable for his associates to help America take the fight to Germany and fascist Italy, the latter of which was feared to have the tacit sympathy of many Italian Americans.

Mafia cooperation was particularly useful during Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Meyer Lansky and a host of other Luciano associates, such as Vincent Mangano and Joe Adonis, recruited scores of people from New York and Italy who had useful information for the Navy, and they would often mention Lucky Luciano’s name if the potential informant was too reticent.

Another key mob member was Vito Genovese, who had fled America for Italy in 1937 and supported the Mussolini regime. With knowledge of Luciano’s cooperation, Genovese swiftly supported the Allies when they invaded in September 1943 and became an interpreter and advisor for the Allied Military Government for Occupied Territories, becoming one of its most ‘trusted employees’.

Doubt still persists about the nature of the mafia’s involvement with the war effort, but the Herlands Report, which investigated the deal between Luciano and the government, gave a favorable conclusion:

Luciano and his associates and contacts were responsible for a wide range of services which were considered ‘useful to the Navy’ during a period when ‘the outcome of the war appeared extremely grave.

As a reward for his efforts, Thomas Dewey, now Governor of New York, grudgingly authorized Luciano’s release on the condition that is exiled to Italy and never returns to the United States.

While Luciano came to terms with his future as he boarded the Laura Keene freighter in Bush Terminal, Brooklyn, his associates gave him an envelope containing around $300,000, which is worth approximately $3,714,276 in 2016 dollars.

Indeed, Luciano’s affluent lifestyle continued in Italy for he was able to conduct transatlantic mob business for much of the rest of his life, albeit on a gradually smaller scale.

However, no amount of luxury could alleviate his miserable homesickness. One small consolation was the California, an American themed restaurant in Naples frequented by American tourists with whom Luciano enjoyed to mingle.

During one of his many visits to Naples, Luciano’s friend Marc Lawrence recollected asking him “What can I do for ya, Lucky?”, to which he replied, “I wanna hear New York talk.” Lawrence indulged him with his strongest New York accent, but it brought only fleeting comfort.

Luciano died of a heart attack on 26 January 1962, aged 64. Three days later, he was buried in Saint John’s Cemetery, Queens, thus ending his 16-year exile from the city that he loved so dearly.

Crime, though, paid much more than average for Charles Luciano, who was truly very ‘lucky’ to have wielded his power during the paranoia and upheaval of the Second World War.

Author: Jack Hawkins