No other one-day battle in the fight to liberate Europe was as costly for Americans as that to take “Bloody Omaha”.

On 6 June 1944, some 73,000 Americans landed in Normandy. More than two thousand made the ultimate sacrifice with by far the highest losses suffered on Omaha Beach with over nine hundred killed. There were untold acts of great boldness and audacity – frontal assaults into the cross-hairs of pre-sited machine-guns depend for their success on courage and aggression above all.

And yet, for their actions on D-Day only four Americans received the highest award for valor, the Congressional Medal of Honor (MOH). Were too few recognized from so very many brave men?

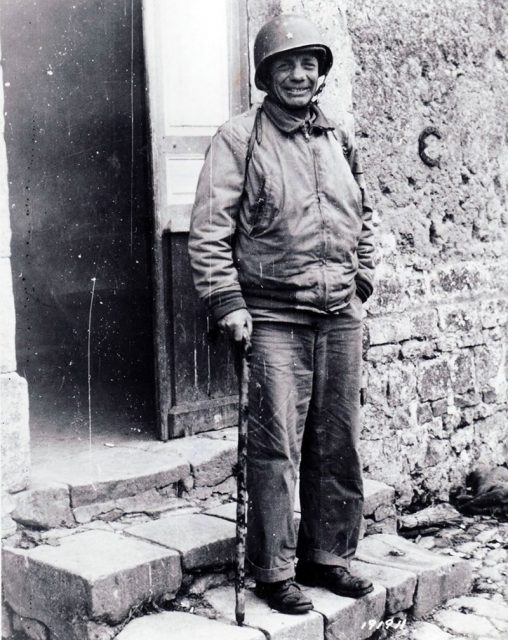

One of the four recipients was Theodore Roosevelt Jr., acting deputy commander of the 4th Division, and the oldest man at age 56 to land in the first wave. He led very ably on 6 June and beyond. Stepping out of a landing craft at around 6:30 AM on Utah Beach was in itself medal-worthy.

Yet his status as the son of America’s 26th President, Theodore Roosevelt, also explains why he and no other man from 23,500 who crossed Utah, or indeed any paratrooper from more than 13,000 who dropped inland of the beach, received the highest award for valor. Patronage and politics played a part, however courageous Roosevelt undoubtedly was.

Other than Roosevelt, who died of heart failure on 12 July 1944, the other recipients of the medal all came ashore on Omaha. From the 35,000 men landed that day on the most fatal of the five landing beaches, some 4,700 men become casualties – missing, wounded, or killed – accounting for around thirteen percent of the total force launched early that morning from the sea.

More than 900 men died there. No other one-day battle in the fight to liberate Europe was as costly for Americans as that to take “Bloody Omaha.” No other stretch of sands in Europe, it might be argued, witnessed so much death as well as courage in WWII.

All three of the men who received the MOH on Omaha belonged to the storied Big Red One, the only US infantry division from three on D-Day that had previously experienced combat.

Technician 5th Grade John Pinder from Pennsylvania had, like many of his comrades, seen action in Sicily with the 16th Infantry. He knew what an MG-42 machine gun sounded like – how it could fire up to 1,500 rounds per minute, three times faster than any American automatic weapon. He knew the shrapnel caused by an 88mm artillery piece could turn men to hamburger. On Omaha, there was hardly any place out of range of both weapons.

Pinder actually landed on his 32nd birthday, probably in the Easy Red sector, one of eight assigned landing zones, and the second most lethal after Dog Green where most of the first wave were killed or wounded in just a few minutes.

Carrying a heavy radio on his back, he was a natural target for snipers enjoying open season – defenders who knew that taking out radiomen was as impactful as picking off officers whose job it was to lead young, terrified Americans into the line of fire.

https://youtu.be/-MUDxA-hpZY

As Pinder stepped off his landing craft, he came under intense machine gun fire which ripped through men nearby. He’d waded just a few yards when he too was hit. Although badly wounded, he managed to make it to the beach with his radio.

Losing blood rapidly, Pinder refused to be treated by a medic and was seen trying to pull another radio and other equipment from the bullet-whipped shallows. The third time he returned to the waterline he was shot in the legs. While setting up radio communication – which would have helped save lives – he was hit yet again, this time fatally.

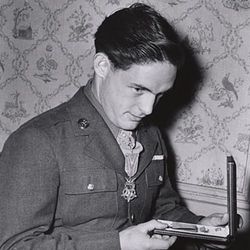

24-year-old Private Carlton Barrett, just 5 feet 4 inches tall and tipping the scales at 125 pounds, was probably the smallest man in the 1st Division’s 18th Infantry Regiment. He also waded ashore under heavy fire. He too was seen returning several times to the water, in his case to save wounded men from drowning.

Even as mortar shells exploded and bullets slashed all around, according to his MOH citation, he “calmed the shocked; he arose as a leader in the stress of the occasion.” He survived Omaha and the war. Forever haunted by the carnage he had witnessed, he died aged 66 in California.

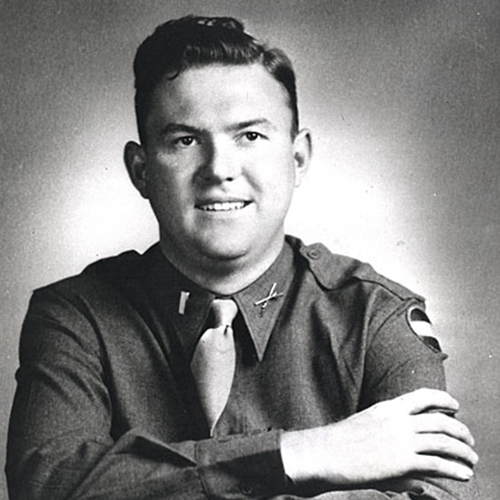

26-year-old, Virginia-born Lieutenant Jimmie Monteith, also with the Big Red One, also arrived when Bloody Omaha was deadliest and managed to organize his unit and get it to relative safety below some cliffs. He then led two tanks through a minefield and directed their fire at enemy strongpoints which were soon destroyed.

After moving off Fox Red sector furthest east on Omaha, he and his men seized a critical strongpoint, WN61, but were then surrounded. Attempting to break out, Monteith was killed.

For their heroism on Omaha Beach, 153 men would receive the Distinguished Service Cross, America’s second highest award for bravery. Some of these DSC awards for extraordinary courage on Omaha should, without doubt, have actually been Medals of Honor. But officials were apparently concerned that too many men would get the highest award and its significance might somehow be diminished.

So in several cases the MOH was downgraded to a DSC by an evaluation board. Had it not been for a personal note from General Eisenhower himself, Jimmie Monteith would in fact have received the DSC rather than the MOH.

Not one man from the other infantry division to land on Omaha, the 29th, received the MOH. Yet so many, namely Assistant Division Commander Norman Cota, were certainly deserving of it, more than showing sufficient “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of life above and beyond the call of duty.”

Unlike the Big Red One, the 29th Division was new to combat and most of the National Guard unit’s officers had never made medal recommendations for a Bronze Star, let alone the highest award with its stringent conditions.

As the 75th anniversary of D-Day approaches it might be appropriate to convene a new evaluation board and look again at the cases of those whose bravery was not sufficiently recognized on D-Day, starting with those who fought on Omaha Beach.

Upgrading several DSC awards would be a fitting act of commemoration. It would make the families of these forgotten inordinately proud, quite apart from correcting an injustice. But what of the recipients, long gone?

Might they shrug and smile ruefully from their graves? Might they simply say, as so many living MOH recipients do: “Thanks, but I was just doing my job. I was doing what any other good soldier would do.”

What do medals mean anyway? Many decorated veterans from WWII have prized above all the combat infantry badge, not an award for valor as such, but a signifier that they were in fact there, deep in the horror and maw, unlike the men on evaluation boards.

They did their part. The recognition of that was more than enough.

Take the case of Audie Murphy, America’s most decorated soldier from WWII. He didn’t rack up 33 awards so he could bask in glory. He wanted to get the war over as fast as he could and the best way to shorten it, in his mind, was to attack and kill the enemy. Medals meant so little to him that he considered giving all of his away when he returned home, covered in ribbons, brutalized and forever broken.

“War is a nasty business,” he told one reporter, “to be avoided if possible, and to be gotten over with as soon as possible. It’s not the sort of job that deserves medals.”

More info for the book: The First Wave