War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

In the years following his service in the Vietnam War, local veteran Larry Fletcher fervently searched for books about the Air Force’s special operations squadrons and the pilots and crews who operated the AC-119G “Shadow” gunships.

When he discovered it was a historical niche largely overlooked, the Air Force veteran chose to fill the gap with a narrative based on his personal experiences.

“There just didn’t seem to be anything about (the special operations squadrons), so I decided to take it upon myself and write about it,” said the Lake Ozark veteran.

A 1961 graduate of California (Mo.) High School, Fletcher pursued an education by attending Southwest Missouri State College (now Missouri State University), graduating with a bachelor’s in education in 1965. The following year, he graduated from the University of Missouri-Columbia with a master’s degree in education.

“My father fought the Japanese in the Pacific during World War II and then worked as a mechanic at the Ford garage (in California) much of his life,” said Fletcher. “I remember him telling me I wasn’t going to be a mechanic like him and that I was going to attend college,” he added.

Initially, Fletcher’s professional outlook did not gravitate toward a military career despite the war raging in Vietnam. Instead, he fulfilled his desire to become an educator by teaching at a high school in Illinois his first year out of college. In 1967, he transferred to St. Charles (Mo.) High School and began teaching several classes while also coaching sports.

“I remember the superintendents had to write letters to the Moniteau County draft board requesting a teacher deferment,” said Fletcher. “But one day, during a current events class I was teaching, a student asked me how I kept from getting drafted.”

Fletcher continued, “When I told him I had a teacher’s deferment, you should have seen the look on his face … like I was a big chicken or something of the sort.”

During a “snow day” at the school, Fletcher decided to visit a local recruiting office and was soon signing the enlistment papers to become an Air Force pilot although he had never before set foot on an airplane.

In June 1968, the young recruit arrived at Lackland AFB, Texas, undergoing a 90-day course designed to train officer candidates in the fundamentals of serving in the Air Force. Upon his graduation later that summer, the newly commissioned lieutenant moved to nearby Randolph AFB to begin 53 weeks of flight training.

“Pilot training consisted of three stages—the first was 30 hours of flying a T-41, which was basically a Cessna 172 used for initial pilot training. After that,” he explained, “we moved on to 60 hours in a T-37, which was a twin-engine subsonic jet. The final phase was 90 flying hours in a T-38 Talon. For a number of years, the T-38 held the world record for climb rate.”

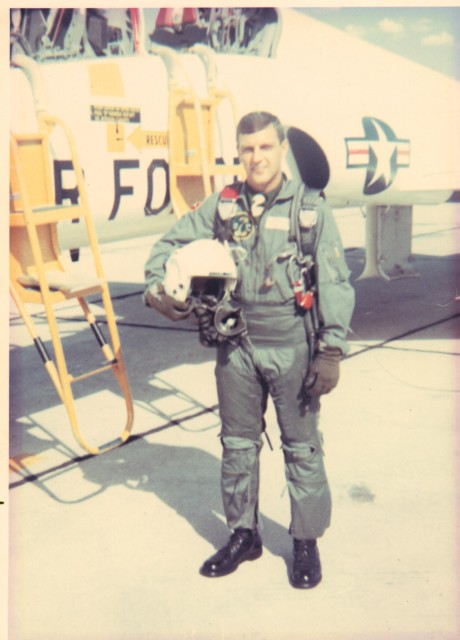

Completing his initial flight training in October 1969, Fletcher received his Air Force “silver wings.” Shortly after that, he learned that he would be assigned to fly the AC-119—a prop twin-engine, side-firing gunship.

Survival and POW training in the states of Washington and Idaho were completed before the crew trained on AC-119 gunships in Ohio. In April 1970, Fletcher received orders for Vietnam, reporting to Tan Son Nut Air Base (near Saigon) as a member of the 17th Special Operations Squadron.

“We flew the AC-119Gs,” he said, “which was the ‘Shadow’ model. It was a twin-engine gunship with four 7.62 mm mini-guns—one gun would fire 6,000 rounds per minute.” He continued, “Our mission was direct close air support of American and Allied ground forces. We could talk directly to the troops on the ground from the airplane and direct our fire as necessary.”

As the former pilot explained, the plane was equipped with a night observation scope (NOS) that would assist in the detection of enemy troops, mortar positions, and anti-aircraft guns. Information from the NOS was processed through an onboard computer and relayed to the aircraft commander pilot’s gun sight.

With a crew complement of four officers and four enlisted personnel, Fletcher affirms that their “Shadow “successfully operated on teamwork, completing 177 combat missions that carried them throughout Vietnam and Cambodia.

“It was like the Wild West with everything going on over there,” he said, “but we were able to save a lot of friendly troops, villages, garrisons, and convoys with our air support.”

After leaving Vietnam in May 1971, the combat veteran remained in the Air Force until resigning his regular commission at the rank of captain on August 15, 1973, to return to his career in teaching. In later years, he earned his doctorate in education at the University of Missouri and served in several educational capacities to include the superintendent of California R-1 School District.

Though retired since 1997, Fletcher has remained active in preserving the history of those who served in the special operations squadrons, dedicated to sharing stories from the Vietnam War that he believes have remained mostly undocumented. He has written several novels based on his experience in the Air Force including “Shadows of Saigon,” “The Shadow Spirit” and “Charlie Chasers.”

“It was the war of our generation … and it was a bad war,” Fletcher said. “When I came back from Vietnam, I had two more years to serve on my five-year obligation. When I separated from the Air Force, I hung up my uniforms and went back to teaching. For years, hardly anybody even knew that I had served in the military. But, I went on thinking that someday a scholar would write about the special operations gunships, but nobody ever did.”

With a brief moment of reflection, he concluded, “These books, everything I have written, is stuff that I carried in my head for 28 years. Much of what we did, especially the missions over Cambodia, were top secret and no one—not even those on the airbase (Tan Son Nut)—knew what missions we had completed.”