War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Archie Barker

A Pan-Hellenic conflict

From 431-404BC, the bitter Peloponnesian War raged across Greece. The conflict, although mainly between Sparta and Athens, involved every important Greek state and changed the balance of power in Greece forever. Its conclusion marked the end of Athens’s Golden Age, and with it an era of cultural enlightenment that gave Ancient Greece its reputation as one of the most advanced civilizations of the pre-Roman world. The battle that finally ended Athenian resistance was their crushing defeat by the Spartan Navy at Aegospotami.

Across Greece, it was common knowledge that Spartan Hoplites could not be beaten on land. Time and again, the elite troops had proven their worth, whether against Persian invaders at Thermopylae in 480 and Plataea in 479, or fellow Greeks at Msantinea in 418. Athens could not compete with Sparta on the battlefield, so she chose to dominate the sea instead.

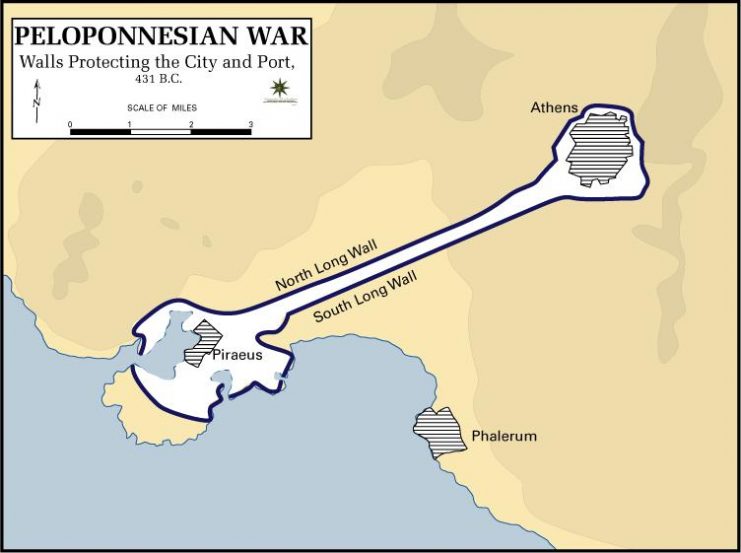

During the 440s, the Athenian general Pericles had the Long Walls constructed. Invulnerable to ancient siege weapons, the walls ensured that Spartan Hoplites could not take the city. Moreover, the powerful Athenian Navy ruled the waves of Ancient Greece, meaning resupply was easy. With such a combination, the Athenians were unbeatable during the early phases of the war. Ironically, it was a naval defeat that finally brought their downfall.

Athenian Decline

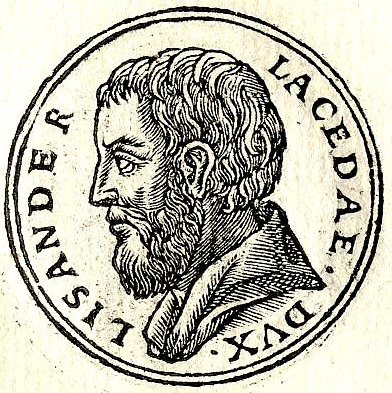

By the end of the 5th century BC, the superiority of the Athenian Navy had long gone, and the Spartans were more than a match for the Athenians at sea. It was for two reasons. Firstly, the Spartan Navy had significantly improved. Naval warfare had traditionally been seen as ‘cowardly’ by the Spartans, but this attitude began to change as Lysander gained authority. The illegitimate son of an aristocrat, Lysander grew up in relative poverty. It was perhaps his unusual upbringing that allowed him to think differently from the Spartan norm. He painstakingly made his way up the ranks and was finally given a position of authority in his mid-forties, when he was made the Spartan Admiral in 407. Lysander borrowed heavily from the Achaemenid Empire and used the money to purchase ships and crews; the Spartans were finally a proper naval force.

Even more important was the devastating defeat suffered by Athens during their ill-fated Sicilian Expedition (415-413). Far from succeeding in its aim to bring Sicily into the Athenian Empire, thousands of Athenians were slaughtered beneath the walls of Syracuse and during the ensuing rout across Sicily. The backbone of the Athenian Navy was shattered: over 200 triremes were lost, 10,000 Hoplites, and most importantly, thousands of sailors. While Athens had the financial reserves to rebuild her fleet, the loss of her incredibly skilled crew was a huge blow. Athens had to recruit mercenaries to sail her ships, and suddenly the quality of her Navy was the same as the Spartans.

The Beginning of the End

Undeterred by this blow, in the final years of the war, Athens was down – but not out.

Despite a decisive naval victory over the Athenians at Notium in 406, Lysander was removed from his command. Conservative elements of Spartan society feared the enigmatic Admiral, and Callicratidas replaced him.

While competent, Callicratidas possessed not a fraction of Lysander’s military brilliance and was soundly defeated at Arginusae in 406, losing 70 ships and his own life when he tried to board an Athenian vessel. The Spartans were still so desperate to keep Lysander away from any power that they even offered generous peace terms to Athens. They were rejected, and Lysander returned to his post. Then, via another generous Persian loan, he restored the fleet to its full strength by 405.

Indeed, Arginusae is seen by some historians as the nail in the coffin of the Athenian Empire. Despite their decisive victory, a storm ensured shipwrecked Athenian sailors could not be rescued, and hundreds drowned.

In one of the all-time worst political blunders, the Athenian Assembly responded by executing the Athenian generals in charge of the battle, rather than celebrating their victory. Athens still had a shortage of military leadership after the Sicilian Expedition, and the loss of their remaining effective commanders gave the Spartans a massive advantage at Aegospotami the following year.

The Final Battle

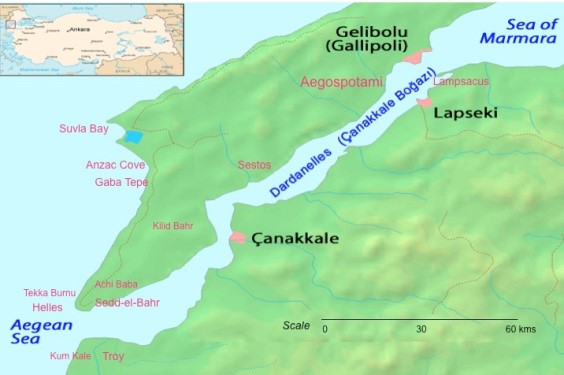

Lysander spent the start of 405 raiding Athenian islands and taking several minor Athenian-held towns. An Athenian fleet of 180 ships led by a committee of generals was dispatched and finally caught up with them at Aegospotami, in modern-day Dardanelles.

The Spartans had a good defensive position in a natural harbor and had 170 ships. The two sides eyed each other warily, with neither willing to attack first. For four days the Athenians rowed out and assumed battle formation but the Spartans, while ready for battle, would not move from their position in the harbor. The result was a stalemate and a daily game of cat and mouse where the stakes could not have been higher.

Fortunately for the Spartans, they had an inspirational leader who had spotted an Athenian weakness.

Many Greek ships lined up for battle each day. Others, believing they were safe in the knowledge that the Spartans would not leave their positions, foraged for food. By the fifth day, just 30 ships stood against the Spartans. Lysander pounced.

His full force of 170 ships attacked the heavily outnumbered Athenians. Quickly routing them, they drove the men towards their comrades on the beach. The majority of the Athenian fleet was captured with heavy casualties. Isolated work parties were overwhelmed and slaughtered, and no sufficient resistance could be organized. A few ships escaped and some foraging parties fled into the forest but the rest were killed or taken prisoner. Spartan losses were so light as to be entirely discounted by the ancient historians.

As the dust settled, the Spartans had taken 3,000 captives. In an act that was later condemned as extremely dishonorable, they had their throats cut. The Athenian fleet had once again been obliterated and from this setback, there could be no recovery.

Conclusion

Without her protective fleet, Athens was vulnerable to attack. After a lengthy siege, the city surrendered unconditionally in 404. Many of its citizens were dying of starvation. The state that had started the war as the most powerful in Greece had been reduced to nothing. A Spartan backed oligarchy replaced her precious democracy, and never gain has Athens wielded anywhere near the same power.

For Sparta, victory at Aegospotami triggered a domination of Hellas that lasted for 30 years. However, Greece as a whole had been severely weakened by the conflict. Aegospotami signified the end of the golden age of Greece. Just 50 years later, the vast majority of the independent polis that had fought the war was under Macedonian control.

Sources:

Xenophon: Helenicca 2

Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War Book 6

Diodorus: Library