War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Though little is known about the early life of Joseph Epps, the veteran of the conflict known at the Philippine Insurrection gained a level of national notoriety when he received the nation’s highest award for gallantry—but 24 years after the heroic actions which earned him the coveted distinction.

Born May 16, 1870 in Jamestown, Mo., Epps was known to be a quiet man and lacking in friends, said Richard Schroeder, a California, Mo., resident who has studied the life of the late veteran.

“I’ve researched newspapers articles about him and interviewed some of his relatives (who are now deceased),” said Schroeder. “He had one close friend while growing up, a neighbor girl who was ten years older. It wasn’t a romance,” he added, “just a close friendship”

As Schroeder explained, the girl died when Epps was 21 years old and his parents passed within the following year, which inspired the quiet man from Jamestown to pull up roots and move to Oklahoma with aspirations of becoming a cowboy.

Though the specific date that Epps left his Missouri home remains uncertain, the December 1, 1928 edition of the The Nashua (Iowa) Reporter noted that in 1899, the Panama, Okla., resident “left his horse and lariat to join the army for service in the Philippines.”

An article in the July 27, 1926 edition of the Reading (Pennsylvania) Times explained that the former cowboy first entered service with Company D, First Regiment of the Territorial Volunteer Infantry from the Oolagah Indian Territory; however, it was his later service with Company B, 33rd United States Volunteer Infantry that would earn him an unexpected recognition.

According to the Texas Military Forces Museum, the 33rd was organized at San Antonio and “recruited almost entirely from Texas.” The regiment deployed to the Philippines in 1899 to help quell an insurrection brewing on many of the islands in the region.

Documentation from the National Archives and Records Administration explains that the Philippine Insurrection unfolded when the U.S. gained territorial control of the Philippines on December 10, 1898 through the Treaty of Paris. Previously, the they had been under the colonial authority of Spain and “(m)any in the islands were not eager to see one colonial power replaced by another.”

Under the leadership of revolutionary Emilio Aguinaldo, the islands soon erupted into struggles of armed resistance, which resulted in the United States sending troops to help suppress the guerrilla activity.

Gregory Statler penned an article for the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center in which he states Company B, to which Epps was attached, was stationed near the Philippine town of Vigan when chaos erupted around 4:00 a.m. on December 4, 1899.

“Shots were being fired; men were yelling; and the sounds of battle were coming from the plaza …,” wrote Statler.

The revolutionaries or “insurrectos” as they became known, with their forces of 850 men, had begun their attack against the town held by a mere 84 soldiers from Company B.

During the battle that ensued, Epps and another soldier received orders to protect an area near a wall adjacent to a churchyard and, to prevent the insurrectos from crossing the wall. Although Company B was able to repulse the initial attack, some snipers remained behind to harass the American forces with intermittent gunfire from behind the wall.

“I want to go and get those fellows behind the wall,” Epps said, according to the January 28, 1932 edition of The Waterloo (Indiana) Press. His request was granted and Epps was accompanied in his mission by Private W.O. Thrafton of Texas.

The article also stated the pair cautiously approached the churchyard, at which point Epps crawled to the top of wall and yelled at the insurrectos in both Spanish and English, ordering them to throw down their rifles and place their hands in the air. Concurrently, Private Thrafton “let loose a typical Texas whoop,” giving the impression there were additional American troops at their call.

“(Epps) believed that his friend from Jamestown (who had died years earlier) was serving as his guardian angel,” said Schroeder. “Before he jumped up on the wall, he heard her voice tell him, ‘They can’t hit you.’”

Complying with the persuasive command, the insurrectos abandoned their weapons, resulting in Epps’ single-handed capture of 21 armed men.

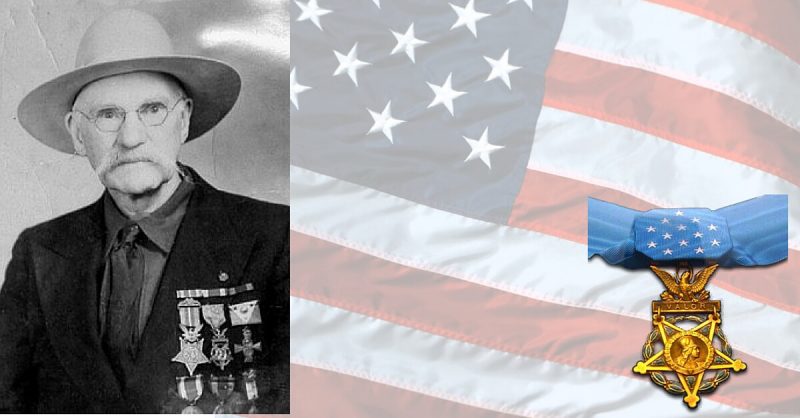

Congress awarded Epps the Medal of Honor in 1902; however, he essentially disappeared from the public eye after his discharge from the Army, thus leaving the medal unclaimed. It was not until he ran across his former captain years later that he learned of the honor he had been bestowed.

“At first,” Schroeder explained, “he didn’t want a big fuss made about the award. But when he learned it included a $10 bonus, he decided to accept it because he thought he could use the money to start up a chicken ranch in Oklahoma.”

On August 13, 1926, a reluctant Epps stood at attention and received the long overdue medal.

“Epps actually received two medals,” said Schroeder. “The first was the medal that was in effect 24 years earlier and the second was the newly designed medal,” he added.

After the award ceremony, Epps, who had previously avoided any recognition, again faded into the background to live his life in seclusion. The veteran passed away on June 20, 1952 and was laid to rest at Greenhill Cemetery in Muskogee, Okla.

“It is truly a unique and interesting story,” said Schroeder, while discussing Epps. “To have a man who was so quiet and essentially friendless while growing up, to then go on to perform such a heroic task during his military service—it’s amazing.

“It is really a great example of humility, that even when in the receipt of the nation’s highest honor (for valor), Epps did not crave the spotlight; he simply wanted to move on with his life and become a chicken farmer.”