On the morning of Saturday, April 7th, 1945 tension aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-12) was times a thousand. The fighter pilots with Hornet’s Air Group 17 were grim after the heavy kamikaze raids the day before but remained optimistic. On this particular day, the skies above them lay in a dull overcast and threatening clouds darkened the horizon in all directions. Six days earlier on April 1, US forces under Lt. Gen. Simon Buckner had invaded Okinawa. Five days after that, on Friday, April 6, suicide planes from Japan and Formosa rained down upon the Okinawa invasion forces by the hundreds. American ships were sunk at random and sailors were maimed beyond recognition all according to the unfathomable fortunes of war.

But for the past 2 months, the aircraft carriers in Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Task Force 58 had been creating their own havoc while raiding in Japanese home waters. It had taken the US Navy over three years of hard fighting to finally get to this area of the Pacific. They would be known as the “fleet that came to stay”. Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, who commanded Spruance’s carriers was nearing the end of a brilliant naval career. Mitscher had been a pioneer and leader in naval aviation nearly since its beginning and now the admiral marveled at how far carrier aviation had come. At the time of the Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor, the US had just 3 aircraft carriers in the Pacific. Now there were over 50.

An eternity had passed since the famous carrier battles of 1942. After the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway in May and June of 1942 the long bloody trek up through the Solomons started with the invasion of Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942. The Solomon’s campaign took over a year to complete. Another year went by as US forces swept through the central Pacific toward Japan. Spearheaded by the ever-growing carrier groups the drive across the Central Pacific began on November 20, 1943 with US Marines landing on Tarawa and Makin in the Gilbert Islands. It was called “Operation Galvanic”.

With this operation fate now intervened, lending a hand to the final destruction of Yamato. The new escort carrier Liscome Bay (CVE 56) with Captain Irving Wiltse, sailed with Admiral Richmond Kelley Turner’s TF 52 departing Hawaii on November 10, heading for the Gilberts. Leading Her air group, Composite Squadron 39, (VC-39) was Lt. Cmdr. Marshall U. Beebe.

Arriving on D-Day… Nov. 20 Beebe and his pilots went to work. Theirs was a hectic schedule and for the next three days pilots bombed, strafed and supported the ground troops. At 05:05 in the early morning hours of Nov. 24, Liscome Bay sounded “General Quarters” and Beebe’s pilots began manning their planes readying for their first attack of the day… suddenly, at 05:13 an officer on the starboard side yelled “Here comes a torpedo”!

The Japanese sub I-175 commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Sumano Tabata had closed the task group undetected during the night and fired a spread of torpedos. Liscome Bay was struck below decks in the most vulnerable spot… the bomb storage area! Most on the flight deck were killed in the resulting explosion and fireball including fourteen pilots awaiting takeoff. Flaming material was blown into the sky hitting the other ships in the area as far as 3 miles away.

Marsh Beebe was in the head at the time of the explosion and after making his way up to the flight deck, and the inferno, was ordered by Captain Wiltse to go as far aft as possible and go over the side. The two began making their way aft but due to the intense heat Beebe realized they could go no further and prepared to go over the side. Beebe turned to inform the Captain but Wiltse didn’t answer… continuing into the smoke and flame he was never seen again.

Another pilot, Frank Sistrunk, was recovering in the medical bay from a recent appendectomy. At the explosion, medical personnel evacuated the area thinking all were dead. Sistrunk found himself alone and began crawling on electrical wires to a gun plot where he was able to drop into the sea. The Liscome Bay sank in 23 minutes. The war was over, at least temporarily for the pilots of VC-39.

But the Navy wasted no time re-assigning the pilots. Beebe and the remaining twenty pilots began training in April of 1944 after rehabilitation leave. The team formed the nucleus for their new squadron… VF-17. Younger, and newer pilots were integrated into the squadron including Lt. jg Robert Good. The new VF-17 arrived on USS Hornet on February 1, 1945 ready for combat. Fates hand would set Beebe to be the first pilot to greet Yamato on her final day!

Two and a half months later, on January 31, 1944 the Marshalls were invaded then, ever westward, the bloody fighting continued through to the Marianas in June which included Guam, Saipan and Tinian, then it was on to the Carolines in September. At last, in October of 1944, the US Fleet returned General MacArthur back to the Philippines as US invasion forces landed on the island of Leyte.

Finally, the long-awaited attack on Japan by our aircraft carriers began with Task Force 58 raiding Tokyo on Feb. 16, 1945. The spectacular Doolittle raid had first hit Tokyo in April of 1942 using Army B-25’s. These bombers were launched from the preceding Hornet (CV-8) which was lost in the Battle of Santa Cruz on October 26, 1942 during the Solomon’s campaign. The earlier Hornet would be the last full-sized fleet carrier to be sunk by Japan though we lost a handful of smaller carriers later. But Doolittle’s was a one-time strike though it did much for American morale. Because the B-25’s were too large to land back aboard Hornet they flew on to China.

By the time we initiated the Tokyo raids in February Mitscher had a total of 16 aircraft carriers in 4 Task Groups! The surprise raid on Tokyo was meant to knock out the air power from Japan which would have interfered with our landings at Iwo Jima, which began 3 days later on February 19, 1945. Iwo Jima lies in range of Japanese bombers from the Homeland. Of the 16 Carriers in Mitscher’s 4 task groups first hitting Japan the Hornet, flagship of Task Force 58.1, was nearest the enemy and was a mere 80 miles from the Japanese coastline when planes were launched on the morning of February 16. Japan had by this time endured large scale bombings by unescorted B-29’s from the Mariana’s but now, seeing enemy fighters from aircraft carriers in the skies over Japan for the first time must have disheartened even the staunchest militarist. Unlike the early stages of the war when US carriers were virtually non-existent, by 1945 the great industrial might of America had gained a powerful momentum. We now produced more ships, aircraft and aircraft carriers than any other nation in the world and were standing at the enemy’s doorstep… just as Japans most illustrious Adm. Yamamoto had predicted… and feared.

Sixteen carriers in 4 separate task groups hit Japan in the initial Tokyo raids on the 16th and 17th of February. Then, after moving south to give direct support to the Iwo Jima landings on the 19th the thousand plus ships of Admiral Spruance’s Task Force retired to our Ulithi anchorage in the Carolines in early March to replenish. But on Wednesday, March 14th Task Force 58 was on the move again. The gigantic ships glided silently out of their newly won anchorage at Ulithi led first by the ever-present minesweepers, then by the quick and nimble destroyer squadrons which protected the Carrier Groups. This time the Goliaths were heading for the airfields around Southern Kyushu in western Japan. Their mission was to knock out Japanese airpower in preparation for the upcoming invasion of Okinawa, codenamed “Operation Iceberg” which was scheduled for April 1, 1945. Kyushu’s airfields were mauled by Navy and Marine air groups for 2 days beginning on March 18. Many of Japans best pilots who had been saved in order to protect the home islands were stationed at Kyushu and were thrown against the Americans in the fierce two-day battle.

Then, during the following 2 weeks Mitscher’s four powerful carrier groups, which still included 16 carriers and over 1,500 planes, raided the islands between Okinawa and Japan knocking out enemy planes wherever they were found… but the fighting was intense and during that two week period the Navy had paid a price. Three full sized carriers, Franklin, Wasp, and Enterprise, had been sent back to Ulithi for repairs. Devastating kamikaze hits during the fierce fighting had severely damaged them.

His task forces weakened now, Mitscher consolidated the remaining 13 carriers into 3 task groups and by Easter Sunday April 1, the ships were stationed between Okinawa and Japan in order to meet the expected suicide onslaught in response to our landings on Okinawa. Though Mitscher’s forces had now been whittled down to 3 task groups after two months of heavy action he still commanded a lethal force.

Now, on Saturday, April 7, only 6 days after our forces landed on Okinawa’s beaches, and after receiving a contact report during the night by one of Nimitz’s cherished subs near the entrance to Japan’s Inland Sea, Mitscher ordered all ships to concentrate northeast of Okinawa. Patrol subs had been sent out by Nimitz several days before in order to keep an eye out for the Japanese battleship Yamato which was still in Home waters. Though much of Japans navy was now sunk, the formidable Yamato and a potentially deadly task force remained. Actually, US subs had been tracking the big ship for over a week but had recently lost her whereabouts. The patrol subs had now relocated her and this latest report correctly identified the behemoth. Yamato had left the Inland Sea near Kyushu and was leading a Japanese task force west toward Okinawa!

Upon receiving the contact report Mitscher immediately conferred with his chief of staff Arleigh Burke. Quick calculations told them the 4 carriers in Task Group 58.1, Hornet, Bennington, Belleau Wood and San Jacinto were at the northern edge of the task force and closest to the enemy ships. Mitscher had purposely assigned Rear Admiral Jocko Clark’s Hornet to the hot corner. Mitscher and Clark had both been raised in Oklahoma and Clark’s aggressive fighting spirit was known throughout the Fleet. Now Jocko’s seasoned air group was about to get first crack at the much sought after prize… Yamato.

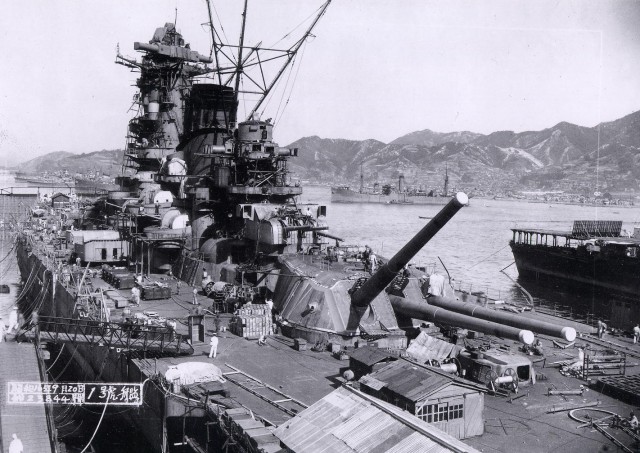

She was the most powerful battleship in the world and the absolute pride of the Japanese fleet. Commissioned in December 1941 at the beginning of the war, her 18- inch guns could reach farther and do more damage than any American or British battleship with their 16- inchers. But she had not been seen in a major engagement since the battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines nearly six months before. In fact, her war record had not been overly impressive. Since before the battle of Midway she seems to have been coddled more or less in nearly every battle so as not to expose her to undue harm. The closest she had come to any real injury was the bombing Mitscher’s aircrews had delivered at the beginning of the Battle of Leyte Gulf on Oct. 24, 1944. Then Yamato had taken a few bomb hits and was thought to have lost heart. She appeared to have turned about and run away after the attack… but Admiral Takeo Kurita, in charge of the operation had other plans. Yamato’s sister ship Musashi was sunk in the attack but after re-grouping the remainder of his ships Kurita reversed course and throughout the dark night of Oct. 24-25 boldly steamed eastward toward the Americans, flawlessly navigating his ships through the treacherous San Bernardino strait in darkness.

Admiral William Halsey, then commanding the US carrier task force, was told Kurita’s force had given up after being routed. Relying on the exaggerated damage reports of his pilots Halsey made a fateful decision and turned north sailing away from San Bernardino Strait which he had been protecting. Japanese carriers had been detected to the north during the afternoon and now Halsey had the bone in his teeth. Indeed Halsey’s orders from Adm. Nimitz were to engage the Japanese carriers if the opportunity presented itself. Due to confusing communications influenced by a divided command structure the critical San Bernardino Strait just north of Leyte, thought to have been covered, was now left unguarded. By the morning of October 25th, Yamato and her accompanying battleships, cruisers, and destroyers sailed through the Strait unmolested and undetected. MacArthur’s return to the Philippines was suddenly in jeopardy!

Kurita pushed south with his strong force and soon, horrified US sailors on scouting destroyers could hardly believe their eyes! Without warning, their predicament was realized when the masts of the Japanese task force could be seen cresting the horizon! Kurita’s persistence had paid off… no one was expecting them. He immediately opened fire from Yamato and began pulverizing our light covering forces north of Leyte at nearly point blank range! For over two hours a wild and furious sea battle raged and only after heroic action typified by the small destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts, was the battle ended. The Roberts and several other destroyers put themselves between our unprotected and thin-skinned escort carriers and Kurita’s force. The escort carriers were now the main protection for the Leyte landings. Their primary task was to provide ground support at Leyte and the last thing they expected was to go up against battleships. Desperately the “little boys” began laying smoke between Kurita’s oncoming force and our carriers to obscure the enemy fire in order to buy time… but they would soon be made to pay the ultimate price. These small type destroyers fought valiantly against Japanese battleships and cruisers at times even charging them in direct suicidal torpedo attacks while firing their inadequate 5-inch guns. Samuel B. Roberts was soon sunk, blasted to pieces by Kurita’s battleships and cruisers along with two more destroyers, Johnston and Hoel. After swatting the destroyers aside Yamato’s attention turned to the US carriers. Unable to outrun the fast battleships the escort carrier Gambier Bay was sunk after being mercilessly shelled by Kurita’s force. Had it not been for the heroic action of the destroyer men our losses would certainly have been much worse. But their gallant work did not go unrewarded. Due largely to their efforts the enemy force had been scattered during the fight losing its once tight formation. Just when Kurita seemed destined to wipe out MacArthur’s lightly protected landing forces the Japanese admiral inexplicably stopped the attack and sailed back north in order to regroup. American commanders could not believe their eyes… and luck, for the meager ships in their command were no match for the much stronger Japanese force. Gen. MacArthur’s return to the Philippines was thus saved.

Clearly, the Japanese did not want to lose Yamato but now with the invasion of Okinawa the Americans were knocking on the back door and the situation was desperate. Okinawa lay a mere 350 miles from Japan’s southernmost island of Kyushu. If Okinawa fell, American short-ranged fighters would be able to use Okinawan airfields to provide protection for the big bombers as they rained down their torrents of steely hell upon the mainland.

Scuttlebutt ran rampant during the morning hours of April 7, as the men of Hornet, Bennington, Belleau Wood and San Jacinto went about their business. But one rumor kept surfacing… Hornet and the rest of Task Force 58.1 was closest to whatever “it” was that was out there! Some were guessing that Japan had assembled one last powerful force and in an all or nothing gamble were speeding out to destroy the fleet. Others had it that massive suicide attacks were about to rain down upon them making the previous days’ attacks look like child’s play. In fact, both rumors held truth. Yamato indeed had been dispatched along with one light cruiser, Yahagi, and 8 destroyers. But now, because of critical oil shortages, the ships carried only enough fuel for a one-way trip to Okinawa. There she was to beach herself if need be and fight to the last man while blasting away at any and all enemy targets. The Japanese were desperate. This last, thin hope of re-enforcing Lt. Gen. Ushijima’s beleaguered troops on Okinawa would be a do or die effort and few of the Japanese sailors expected to survive. This last ditch sortie of Japans once proud and seemingly invincible navy was code named “Operation Ten-Go” and most, including its commander Vice Adm. Ito on Yamato had written final letters home.

The one thing Lt. (jg) Bob Good and the rest of the fighter pilots in VF-17’s “Jolly Rogers” did know for sure was that 44 aircraft were being held in ready-reserve on Hornet’s flight deck. The men had sensed something big was up and the pilots were keyed. Good had missed out on the big kamikaze raid the day before due to regular pilot rotation. (47 enemy planes were splashed by Hornets air group). Today he was eager for action. The stocky, sandy-haired lieutenant from Eugene, Oregon flew wing to Fighting 17’s skipper Lt. Commander Marshall Beebe. Good had earned that honor by his no-nonsense flying and the fact that he was the only one to out-shoot Beebe during their training at Alameda Naval Air Station. In order to sharpen reflexes, Beebe regularly had taken his squadron out to the edge of the airfield to shoot clay pigeons. The first time out with the group Beebe raised his shotgun and proudly scored an impressive 24 out of 25 hits. Bob Good then stepped up… but he didn’t miss any!

“By Gee if you can shoot like that I’m going to make you my wingman!” Beebe had said. The four plane divisions had just begun training together and Beebe literally and figuratively took Good under his wing. Beebe was a hell bent for leather pilot and “Daddy” Bob Good expected to be in the thick of it… whatever “it” was. First-rate wingmen were hard to come by and Beebe’s choice proved to be an excellent one.

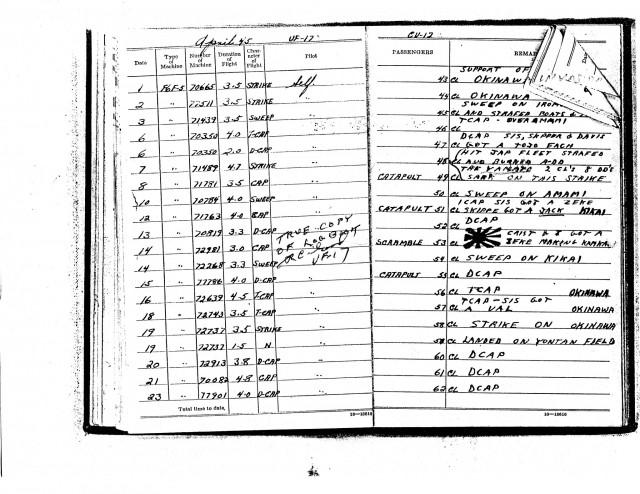

In the early morning of April 7, Hornet had launched 4 of her night fighters on a pre-dawn heckling mission around Kikai Shima but they had found little action. Finally, just before daybreak the 4 Hellcats had to settle for a strafing run on Wan airfield in which the pilots, Burnett, Humphrey, Idelson and Thomas each claimed a single engine on the ground as “probably” destroyed. At 5:50 that morning a four-plane combat air patrol led by Lt. Troute was launched to keep an eye out for intruders but the rest of the pilots were being held in ready reserve and tension was building.

Mitscher had narrowly missed sinking Yamato the previous year at Leyte and now, armed with this latest contact report hopes were renewed. Vice Adm. Spruance who was ultimately in charge had decided to send in the big guns of the fleet under Rear Adm. Morton L. Deyo to intercept Yamato and her fleet forcing a final classic “Battle Grande” however, Mitscher had no intention of letting things get that far. He’d argued for years with old school battleship advocates that he could sink any ship afloat with his airplanes and this might be his last chance to prove it. The war was quickly winding down. Spruance’s orders did not specifically forbid him to attack with airplanes, only to let the enemy fleet come south. Well, they had come south far enough as far as Mitscher was concerned and that was all the excuse he needed to get his foot in the door and settle the argument once and for all.

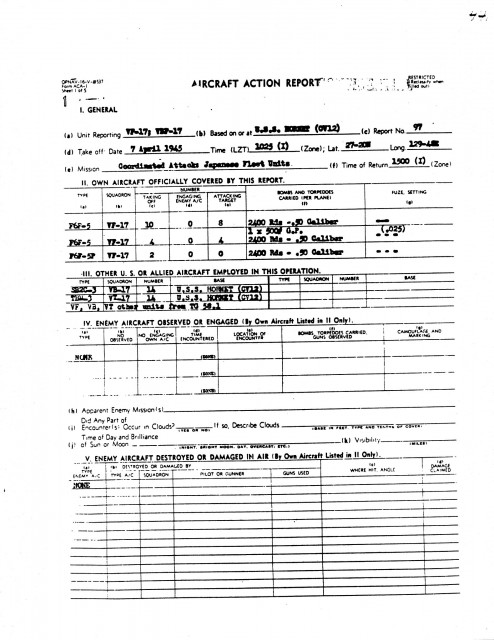

Over the ship’s intercom, the call to man planes came to Hornet’s ready room shortly after 10 a.m. A search plane from Essex had contacted the enemy fleet 240 miles nearly due north and slightly west of the task force. Hornet, in TG 58.1 was indeed closest to the target and Beebe wasted no time getting his men topside. But as his pilots began climbing into their mounts something went wrong. The 500 lb. general-purpose bombs the fighters were ordered to carry were not ready! Some of their alcohol accelerant had been nefariously siphoned off by men of the crew the night before! The alcohol was much prized by certain members of the ship. Beebe wasted no time in making the decision. They couldn’t wait… they would launch with just the standard full load of 2,400 rounds of .50 caliber for their wing guns.

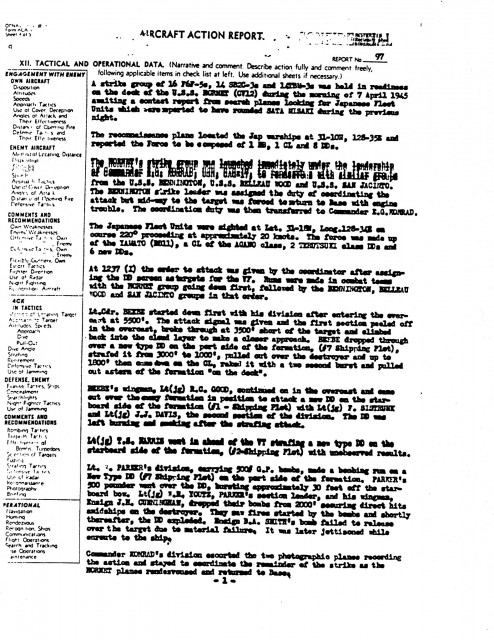

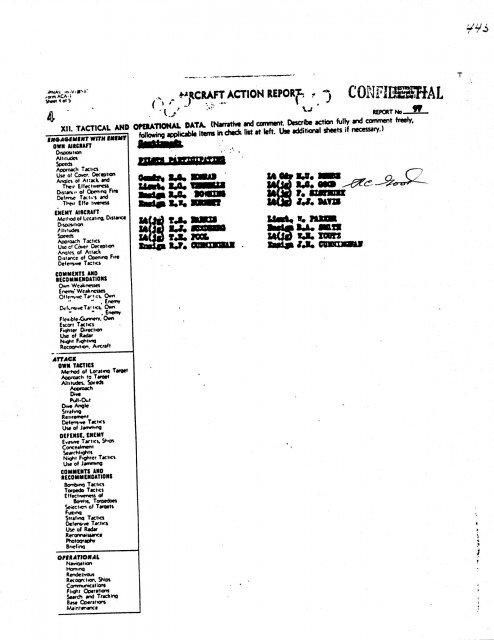

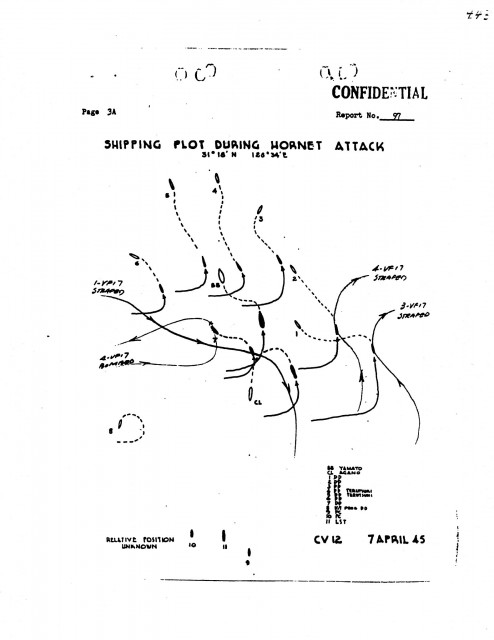

At 10:25 a.m. E.G. Konrad (Commander of Air Group 17) led the group of 44 planes off Hornet’s flight deck. Sixteen F6F-5 Hellcats from Fighting 17 (VF- 17) took off followed by 15 bomb-laden Helldivers from Bombing 17 (VB-17) and 14 TBM Avengers from Torpedo-17 (VT-17). By the time Lt. Parker’s division launched (the last from VF-17) ordinance men had the bombs ready and quickly mounted them onto Parker’s 4 Hellcats. Only 4 out of Beebe’s 16 fighters carried enough ordinance to do some real damage! Within 20 minutes 280 lethally armed airplanes from Task Forces 58.1 and 58.3 were launched and on their way to the target. Mitscher was holding his third group, the 4 carriers in Adm. Radford’s Task Force 58.2 in reserve.

Beebe’s Hellcat roared off the deck and clawed its way up through the thick clouds as Good tucked in tight alongside. Lt. Frank Sistrunk and Lt. (jg) Jack Davis closed up behind completing Beebe’s second section. The weather was scuzzy and marginal at best and a moment’s inattention by a pilot could find him disoriented and alone… possibly leading to a dismal solo flight back to the ship.

Mitscher, with a soft spot in his heart for Marines, had assigned Bennington’s Corsairs to lead the charge but this day lady luck was smiling on Hornets’ Jolly Rogers. Halfway to the strike, the Marine commander’s Corsair developed engine trouble. The Bennington pilot was beside himself but there was nothing he could do. The lead was passed to Hornet as he and his wingman reversed course. Beebe was elated…this meant that his division would be the first down!

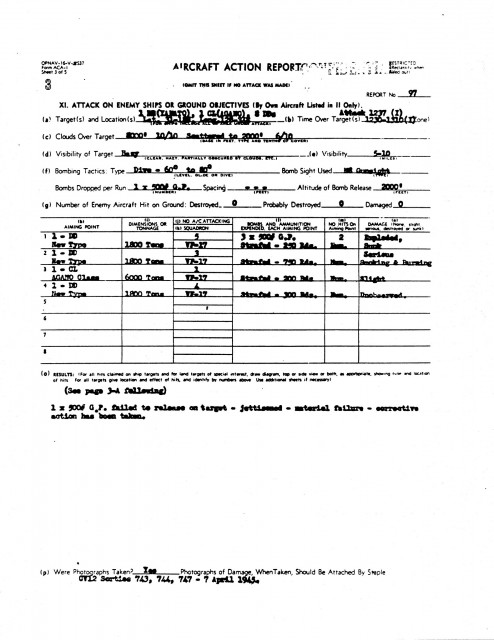

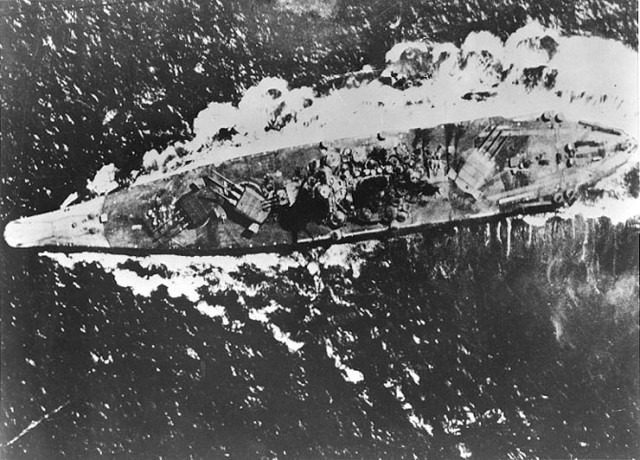

By noon eager eyes scanned the occasional breaks in the clouds and radarscopes were tuned and checked and last minute preparations were double checked as the pilots closed the enemy. The tops of the overcast were at 8,000 ft. with a broken layer of clouds below which were scattered down to about 1,500 ft. Suddenly, through a break ahead, wakes could be seen! Commander Konrad quickly assessed the situation and at 12:37 p.m. gave the order to attack. Konrad directed Beebe’s fighters to first hit the protective ring of destroyers surrounding the two big ships, in order to make the “eggs” in the middle of the basket more vulnerable. Beebe motioned to Good and the Hellcats started down into the scuzzy layer below. The four Hellcat’s entered the overcast at 5,500’ and at 2,000’ dropped through the bottom only to find their approach was short! Yamato’s 18-inchers began firing immediately. Quickly Beebe pulled back up into the soup. Breaking out briefly between cloud layers he motioned Good to take Sistrunk and Davis to the other side of the task force and hit the destroyer screen there. The next thing Good knew he was alone with Sis and Davis. Beebe was gone, already dropping toward the center of the enemy force on his own only this time his approach had been perfect as reported by the fierce guns of the light cruiser Yahagi. For an instant every gun in the Japanese fleet seemed trained on Beebe’s plane. As his Hellcat roared downward Beebe’s airspeed quickly passed through 300 knots. His plunge through the clouds had put him on course for a perfect strafing run on the destroyer just off Yahagi’s port bow. Six 50’s opened up as the twisting Grumman lined up on the destroyer and molten steel hammered the foredeck as Beebe’s guns found their mark. Now, with a slight kick of left rudder, Beebe opened up on Yahagi just as Good, Sistrunk and Davis were breaking through on the other side. Beebe’s guns cut into Yahagi from stem to stern and with a full two-second burst peppered the bridge. Intense anti-aircraft fire filled the sky and immediately turned toward the next three Grumman’s.

Good had broken out over a new type destroyer that trailed Yahagi and Yamato slightly behind and to the right. With Sistrunk and Davis spread behind, the three fighters began a steep dive concentrating all their guns into the turning ship. A mass of steel rose from the destroyer and engulfed the Hellcats. Bingo! Their months of training paid off handsomely and explosions could be seen on the destroyer which was left burning and smoking. Immediately Good pulled out to the right and astern toward Beebe who was retiring on the deck at full speed.

The full fury of the attack now unfolded and adrenaline skyrocketed as the spectacular color-filled anti-aircraft bursts surrounded the airmen’s concentration. Steady hands trembled and hearts raced. Many of the pilots had never seen the array of brilliant multi-colored smoke that marked the individual Japanese gunnery sections.

As Good, Sistrunk and Davis re-formed with Beebe, they spotted two Hellcats from Parkers division diving through the clouds with their 500 pounders! Willie Youtz (pronounced Yewts) had spied a destroyer directly below him through a break and immediately rolled into a near vertical dive and began to gain airspeed. His wingman Jim Cunningham followed but Youtz quickly realized their angle was too steep. The two Hellcats corrected with a lazy, spiraling turn in order to lose airspeed. This allowed them to keep their sights locked on target and at 2,000’ Youtz and Cunningham let loose their bombs. Kawoomph!! Two direct hits! The destroyer below shuddered from the impact and immediately lost speed as tremendous shock waves rippled the sea around the stricken ship. Soon afterward it was seen to explode and go under. One down! Lt. Parker’s Hellcat was seen next as he and Ens. Smith dove ahead of Youtzs’ exploding destroyer and into the heart of the formation. Parker’s target was the next destroyer in line, which was cruising several hundred yards behind and to starboard of Yamato. Parker began his dive and released his bomb toward the wildly turning destroyer. But at the last instant, its Captain ordered an emergency turn and Parker’s bomb exploded harmlessly into the sea causing only minor damage. Smith was next down and he had the destroyer bore sited but as he released his bomb a sick feeling hit him. Immediately he knew something was wrong. The bomb release had jammed and the bomb was stuck tight to the bottom of the Hellcat. Furiously Smith tried to pull out from his dive and the Grumman strained as the extra weight of the bomb pulled him toward the sea. Finally, only a few feet above the licking waves his machine leveled out. As relief washed over him he began yelling loud profanities and cursed the release mechanism. But it was all over. Parker was retiring and it was his duty to follow. (Ensign Smith’s bomb was finally jettisoned and fell harmlessly into the Pacific as the division returned to Hornet).

That was the last distinguishable action that could be seen by Hornet’s retiring VF as Beebe ordered Good, Sistrunk and Davis back to base. An Avenger had been badly shot up and as was typical for Beebe, he took the job of escorting the crippled plane back to the fleet. Both planes made it back safely and the injured crewmen were saved.

The melee that erupted next was without equal. The mass confusion of screaming airplanes, powerful explosives and colored anti-aircraft fire made the entire arena surreal. Pilots, both scared and exhilarated by the spectacle filled the sky as the Grumman’s and Corsairs began unleashing literally tons of ordinance on the enemy ships. Soon another destroyer went under and hits were recorded on Yamato. Yahagi was staggered after being hit repeatedly and was losing way.

The unlucky ships of the Japanese armada were in disarray and had no time to even complete the care of the wounded before Adm. Mitscher’s reserve strike group of 106 planes arrived. Mitschers’ first strike had scored 8 torpedo and 5 bomb hits. Two of the destroyers below were burning fiercely and although Yamato had taken some damage she was still making good way. But she was now listing to port as the second wave of attackers entered the area. Most of her guns were still firing and even her 18-inchers were still letting go at the enemy planes. Yahagi lay dead in the water with oil and gasoline spewing from her bowels. She would soon sink. The Yorktown group passed over her in favor of the crippled Goliath. By now Yamato’s list to port was severe enough to expose her lightly protected underbelly and Yorktown’s Avengers swung around to her starboard in order to take advantage of her weakness. Finally, almost mercifully, the Yorktown planes finished the job, sending the giant battleship to the bottom of the sea. A tremendous explosion ensued which fliers 50 miles away reported seeing.

The extra hundred planes had been enough, for upon their departure only 5 destroyers were left afloat and one of them, the Kasumi was damaged beyond repair and was sunk by the Japanese destroyer Fuyutsuki on the way home in order to prevent her from falling into enemy hands. The last four, Fuyutsuki, Yukikaze, Hatsushimo and Suzutsuki headed for Sasebo. The last to reach Sasebo was Suzutsuki. In sinking condition and aflame at the stern she made the dry dock in Sasebo late in the evening of April 8. Full of survivors, the battered destroyers would be all that would limp back to Japan to tell the story.

The old argument of which ship was the most powerful was settled. Marc Mitscher slept soundly that night. He had been at the forefront of Naval Aviation nearly since its birth and the thought of his airplanes sending the biggest battleship in the world to the bottom of the ocean pleased him. Three hundred eighty-six aircraft were launched in the Yamato attack. Unfortunately 3 Hellcats, 3 Avengers, and 4 Helldivers were lost. Four pilots and eight crewmen would never celebrate the victory.

Meanwhile, the battle over Okinawa continued to rage and on May 28, six weeks after Yamato was sunk, it was Adm. Halsey’s turn to command the big ships. Spruance left immediately for Pearl Harbor in order to help plan for the invasion of Japan which was scheduled for November, 1945. Mitscher stayed on for a few more days to help with Adm. John S. McCain’s transition. With the change of command, McCain would take over Mitscher’s job commanding the carriers.

Ten days after the change of command circumstances put Hornet and the rest of Halsey’s Task Force, which was now designated 38, into the path of a major typhoon. Halsey seemed to be a typhoon magnet and on the 6th of June wild winds whipped at the ships. In the fierce seas Hornet’s flight deck began to heave and groan… then, steel and wood began to buckle and suddenly the first 20’ of her forward flight deck came crashing downward. Hornet’s bow now looked as if it had a broken nose which was resting on its chin! During the storm Bennington shared the same fate. This event was not without a certain irony… for out of all the kamikazes that had rained down on Task Force 58 in the previous four months, Hornet and Bennington were the only two carriers to have escaped damage from their attacks. Mother Nature had finally done what the Japanese could not!

Indomitable Jocko Clark had Hornet in fighting condition two days later and on June 8, he ordered strikes launched off the fantail while backing into the wind! On the 10th of June Hornet launched her last strike of World War II. It was a rocket attack on the tiny island of Okino Daito east of Okinawa. We were softening up the small island in preparation for its capture. As it turned out we didn’t need it and it was never invaded. The 12 participating Hellcats came back without damage. No enemy was observed or engaged in the air. In the action report the only comment of interest about the mission was that two of the HVAR’s (rockets) had failed to fire.

Hornet was then ordered to Pearl Harbor for repairs and on the 29th of June VF-17’s Jolly Rogers flew their last mission. A couple of hours out of Pearl, with all the stories, accolades, and memories of the horrific battles… lost comrades… and the emotional experiences of 20 lifetimes to take home with them, the final wartime entry into their logbooks was written: “Hornet to Pearl”.

A week earlier, on June 22, 1945 at Okinawa, Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima committed hari-kari and died by his own hand as American soldiers surrounded his bunker. Unfortunately Gen. Simon Buckner who commanded the US ground forces did not outlive his adversary. Only a couple of days before, while visiting a forward command post, he was killed by a direct hit on his position during a Japanese mortar attack.

Two thousand US sailors had paid the ultimate price during the Okinawa campaign. This (comparatively) short and intense period of fighting left the US Navy with the highest loss of life in its history. Vice Adm. Marc Mitscher’s job was done. Mitscher flew to Washington upon being relieved by McCain and arrived there by the 5th of June, thereby just missing Halsey’s typhoon. Soon after returning he was promoted to Deputy Chief of Naval Operations, a desk job he admittedly was not looking forward to. Mitscher’s heart had always been with the big ships at sea and finally on March 1, 1946 a fourth star was pinned on his uniform and he was made full Admiral. With it came the command of the newly established 8th Fleet. But the stress of war had taken its toll. (Mitscher had twice been bombed off his flagship by kamikaze’s during the Okinawan campaign) While continuing to serve the navy he had loved all his life a heart attack claimed the much-loved admiral on Feb. 3, 1947. He was so loved by the sailors of the fleet that ships up and down the East Coast lowered their flags to half-mast in tribute after hearing the sad news.

Lt. Commander Marshall Beebe remained in the Navy after the war and was later assigned to USS Essex and flew F-9 Panthers during the Korean War. He had been promoted to CAG of Air Group 5. Ten years later he made flag rank and was named Captain of the Aircraft Carrier Bon Homme Richard. Captain Beebe later became Commander of Task Group 77.4 in the Seventh Fleet, essentially the same job Adm. Jocko Clark had held on Hornet during World War II.

As a sidelight, author James Michener dedicated his novel The Bridges at To-Ko-Ri to Marsh Beebe. In fact the story was based loosely on Beebe’s experiences during the Korean War. The main character, played by William Holden was based on Frank Sistrunk whom Beebe, like many in the Hornet squadron had loved and trusted. After being named CAG on Essex, Beebe contacted Sis asking him to come back to active duty in order to fly with him in his new squadron. Though Sistrunk had not been checked out in jets, he gladly agreed. While flying a propeller-driven Douglas Skyraider on the To-Ko-Ri mission Sistrunk’s plane was struck by the intense flak and he was wounded. Beebe stayed with his friend after the attack in an attempt to get him home. During the flight back Sis began fading in and out of consciousness. Beebe nudged wings with Sistrunk’s plane in an effort to try to keep him awake as was depicted in the movie but Sis finally lost consciousness and crashed. Losing his dear friend was a tough blow for the commander. Marshall Beebe retired from the Navy in 1963 at the rank of Captain. His passing was on August 6, 1991

By Aug. 6th 1945 Lt. (jg) Robert C. Good had returned to the States and was on his way to Jacksonville Florida. He had been selected to lead one of the new four-plane combat teams which were training for the invasion of Japan when the Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Instead of another war deployment… he married his sweetheart. Good stayed active in the Naval Reserve after the war and a prominent life full of flying and adventure followed. He retired from the Navy Reserve in July of 1969 at the rank of Lt. Commander and resided with his lovely wife Bonnie in Eugene, Oregon. Lt. jg Robert C. Good passed away in Eugene, Oregon recently at the age of 96.

The experience of that war has served ultimately to create a completely unbreakable bond between the young men that flew from Hornet’s flight deck. The remarkable kinship they share reflects the life and death struggles in which they participated in, and only they can know. Like so many others throughout the U.S. Navy and the rest of our armed forces, the passing of time has only served to strengthen their kinship. USS Hornet now resides as a floating museum in Alameda California. The surviving members of Hornet’s Air Group 17 still meet regularly.

Written by Barry Smith