War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

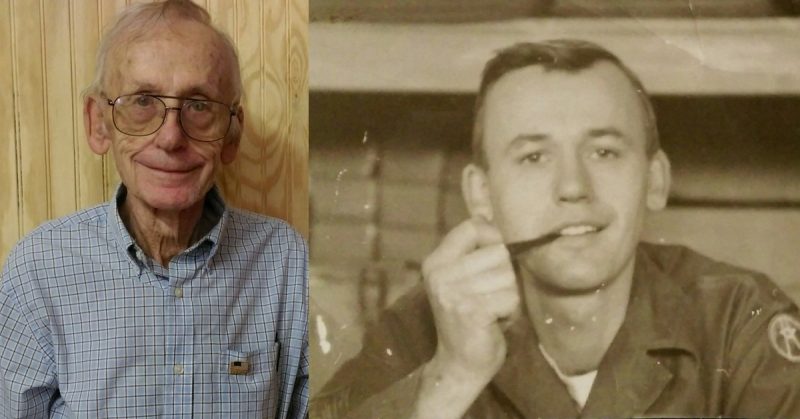

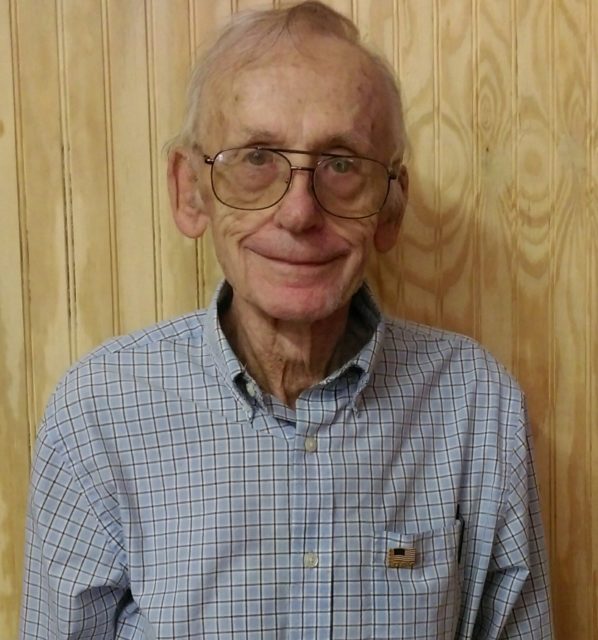

A common theme that often emerges among veterans of the Korean War era is that their service was unexpected and often necessitated by a draft notice. Such was the case for local veteran Don Wyss, who insisted that although unanticipated, his service in U.S Army provided him a key lesson in leadership that he later incorporated during his career in education.

Raised in the small Moniteau County community of Enon, Mo., Wyss explained that following his graduation from Russellville High School in 1946, he began teaching class at a one-room schoolhouse while also attending college part-time during the summers.

“I learned more teaching in that small school than I ever did in college,” Wyss grinned. “But in 1950, I resigned as a teacher and started attending college full-time to finish my degree.”

The Korean War began while Wyss was approaching completion of his degree and he soon realized the likelihood of being drafted. In an effort to acquire some control over his military career, he attempted to enlist in the Coast Guard.

“They tested me for color blindness and I failed the test,” recalled Wyss. “So I thought I might be able to get my commission in the Navy and managed to pass the test.” He added, “They told me they’d let me know if I was accepted into the program.”

While awaiting a response from the Navy, he went on to graduate from college in Warrensburg, Mo., in May 1952 with a degree in science and physical education. However, as Wyss explained with a hint of levity, the week after leaving college, he received his draft notice from the U.S. Army.

Within days, he was inducted at Kansas City and sent to Camp Crowder, Mo., to process into the Army as a private. He then boarded a train bound for Camp Roberts, Calif.—a WWII post re-activated as a training site during the Korean War— and completed several weeks of basic infantry training.

“I remember when we pulled into Camp Roberts, they were shooting .50 caliber machine guns … with all that noise just blasting,” Wyss said. “That’s when I thought to myself, ‘This is for real.’”

The newly minted soldier then received orders for Fort Ord, Calif.—a former Army base situated on Monterey Bay along the Pacific coastline. It was here, Wyss said, that he completed eight weeks of supply school.

“I ended up back at Camp Roberts in late summer 1952 and worked as a supply sergeant in a basic infantry training company until receiving my orders for Korea in August of 1953,” he said. “I had learned to take orders and decided that I would go to Korea and just do the best that I could do.”

The soldier departed California aboard a troopship and, following a brief stop in Japan, arrived in the South Korean port city of Pusan, approximately a month following the signing of the armistice agreement.

Upon arrival, said Wyss, he was assigned to a quartermaster company on an Army base in Pusan, essentially “living in the supply room” and issuing various types of provisions and equipment to his fellow soldiers.

“Pusan was really a mess at that time,” recalled Wyss. “There were people living in cardboard shacks everywhere and there was a stench, it seemed, that hung over the entire city.”

In late November 1953, the odor of filthy living conditions was overpowered by the stench of smoke when a Korean housewife “left a charcoal burner unattended for a few moments and it tipped over, igniting the straw-matted floor,” reported The Tipton Daily Tribune (Indiana).

This sparked a blaze that was fueled by winds up to 30 miles an hour, destroying one-sixth of the city and resulting in an estimated 45,000 homeless. Many of these displaced persons were provided temporary shelters in U.S. Army warehouses.

“After the blaze started, I was ordered to issue live ammunition to the troops,” said Wyss. “At that time, with the fire and all of the activity, they thought the communists had started the war again.”

Days later, as the fire subsided and the cause of the fire realized, the live ammunition was turned back in to the supply sergeants and the rebuilding of the decimated city began.

Wyss remained in Korea until March 1954, traveling to Ft. Carson, Colo., where he received his discharge weeks later. The years following his discharge focused on both family and education as the veteran was married, raised three children and earned a master’s and doctoral degree using the GI Bill benefits he earned in the Army.

Throughout the years, the former soldier served in several leadership positions in education ranging from high school principal to vice-president of a university prior to his retirement in 1983.

Although he admits the ravages of age may have weakened his physical stamina in recent years, Wyss affirms that the value of the lessons he received in the Army has provided him unyielding inspiration throughout his entire life.

“I’ve drawn many lessons from my time in the service such as the importance of being of service to others—your family, your church and your country.”

He added, “A good soldier doesn’t complain and a good soldier doesn’t make excuses; you do your job to the best of your ability,” Wyss said. “But most importantly, the Army demonstrated to me that you can’t be a good leader until you learn first to be a follower.”