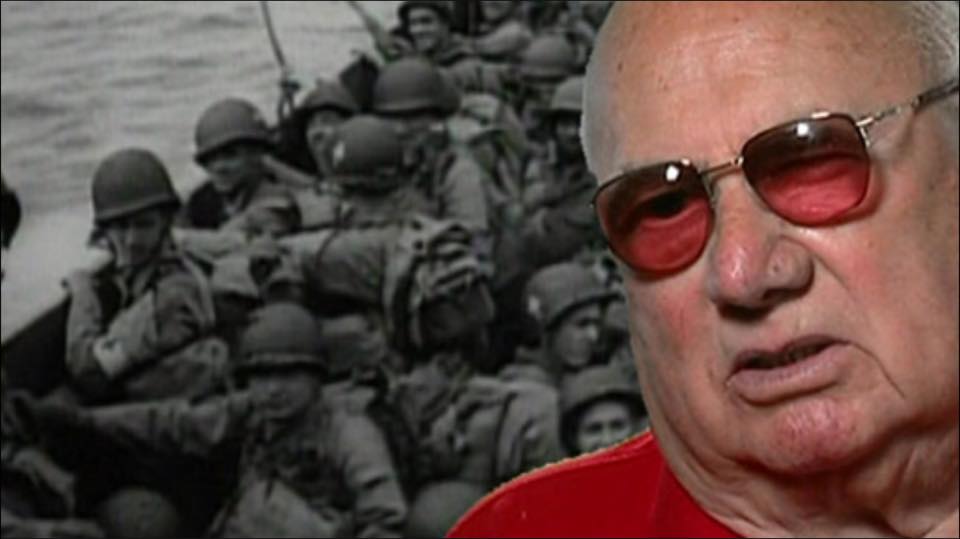

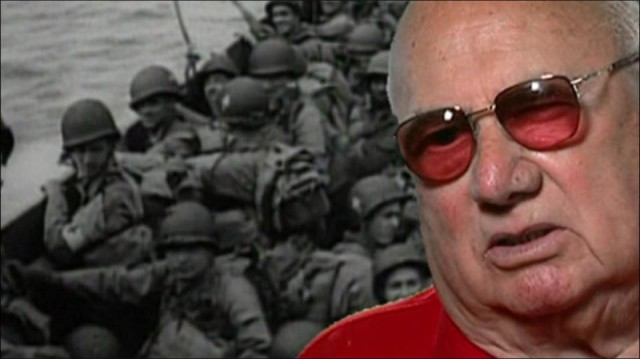

I didn’t try to choke back a sob when I learnt that Bob Sales had passed away on 23 February, aged 89. I’ve spent a fair bit of time over the years with some truly amazing veterans, but none whose company I enjoyed more than Bob’s. He was a very funny man, or at least I thought so. This was all the more remarkable given that he didn’t have a lot to laugh at, at least not in WWII.

Sales landed on the bloodiest sands for any American of the 20th Century, perhaps in all history, Dog Green sector of Omaha Beach, around 7am on June 6 1944. A proud Virginian, he belonged to Company B of the 116th Infantry Regiment of the 29th Division, having joined the National Guard aged 15 by lying about his age. Three years later, aged eighteen, he was the only man from his landing craft to survive the worst carnage on D Day. In fact he was my main and most reliable eyewitness as to what happened to the Bedford boys who had landed just minutes before him and had been quickly slaughtered, whose bodies he saw as he tried to get across the deadliest sector of any beach in Normandy at the deadliest possible time, indeed as German machine-gunners killed any man who so much as twitched as the wounded lay frozen, the tide lapping at their heels. Death surrounded him, goaded him, haunted him, for another six months in France as he killed and watched so many more young men die before he too, inevitably, became a victim.

Sales was a good-looking son-of-a-gun, as he might have put it, a horny teenage ‘Yank’ on a last weekend pass in London before the invasion. In his home in Lynchburg in 2002, in view of the memorial to his fallen comrades he had built in his backyard, he answered me honestly when I asked him what was the moment he felt proudest to be an American in WWII. It was when he heard Tommy Dorsey and his band start up, at the Covent Garden Opera House, some dreary day that spring of 1944. He loved the jaunty tempo, the heady upswing, the feeling he had when he stood up and moved toward the packed dance-floor in his crisp uniform, wearing polished leather shoes and a tie. Those English gals thought he looked like a mighty fine officer, a gentleman, not a lowly private, just as it should be for a charming southern boy with a cheeky glint in his eye, whose unit traced back to the Stonewall Jackson brigade, legends of the Civil War.

He loved England, my place of birth, all his long life. He wrote to friends there for decades, kept in touch with a people who’d dubbed his division ‘England’s Own’ because it was based there for so long, from late 1942 to June 6 1944. He had risked his life beside Brits, he never, ever forgot to mention the heroism of the British naval crews who took him and his buddies onto Omaha. It enraged Sales when false stories appeared, spread by Americans of all people, about his commanding officer having to put a gun to a Tommy’s head to make him land Company B on time and in the right place.

Sales loved to dance, especially with English girls. Churchill had Covent Garden opera house converted in to the biggest dance hall you ever saw in your life, he told me, a big smile on his face, a wry lilt to his Virginia drawl. They had two bands there. One would play for a while then the stage would rotate and another would start up. If you were dancing with a girl you didn’t like, you waltzed over to the stag line and got another. Wrens, Wacs, always two hundred standing waiting to dance. They loved to dance, those English girls. Man, it was as close to heaven as you could get.

If Bob and his buddies didn’t get lucky in Covent Garden, there were plenty of ‘Piccadilly commandos.’ He didn’t miss a beat as he reminisced, my tape recorder flashing red, capturing his every word: ‘Half a pound, occasionally a pound if she was real good looking. It was just unreal when it came to that… There was also a Red Cross hostel where you’d spend the night for nothing. A bunch of girls from Spain worked as maids there. They’d sing, carry on, and laugh as they made our beds. When you were screwing one of them, the others would sing so the supervisor wouldn’t catch on. It was the darndest thing you ever seen. Then you’d slip them two shillings.’

That little confession came back to haunt both of us. It was May 2003, at a Walmart in Lynchburg, where my book the Bedford Boys was being launched. I was stunned to see well over two hundred people turn up for a signing. Suddenly, from nowhere it seemed, a portly man in a wheelchair was at my side.

‘God damn, Kershaw, you put it all in the book! I mean all of it, man!’

For a moment, I was worried he might slug me, teach a cocky limey a thing or two. But then I saw the big smile on his face and heard the chuckle and the laugh. Thinking back to that humid day in a Walmart on Memorial Day I now have tears, as I write, in my eyes. I realize now I loved Bob for his honesty and wit and because he made the war real and romantic and terrible to me, born twenty years after he finally came home.

He survived the very worst. As a radio operator, he was beside his commanding officer just before 7am on June 6th. Captain Ettore Zappacosta, Company B’s commanding officer told Sales to ‘crawl up on the edge and see what you can see.’ The beach was a stone’s throw away but Sales couldn’t see anybody from Company A fighting ‘ the Bedford boys belonged to Company A and had landed at H Hour, 6.32am. Of the 19 men from Bedford County, Virginia, who died that day, most were already dead, their corpses strewn across the beach ahead of Sales.

‘Captain,’ shouted Sales, ‘there’s something wrong. There’s men laying everywhere on the beach!’

‘They shouldn’t be on the beach.’

A British bowman said he was going to drop the ramp. Sales ducked down. Zappacosta was the first out. MG-42 bullets riddled him immediately.

‘I’m hit, I’m hit,’ he called out.

Every man who followed met the same fate, caught in a relentless crossfire.

Sales would have been hit too but he stumbled as he exited, lost his balance, and fell into the water off the side of the ramp. He was still wearing his radio. He struggled in the water to release it; if he didn’t get the damned thing off his back, he knew he would never fill his lungs with air again. Sales finally ripped the pack free and surfaced. He was several yards in front of the craft. The machine guns were now enjoying open season. Men were still exiting, still dropping the instant they appeared on the ramp.

‘Those German machine guns,’ Sales told me, ‘they just ate us up.’

A mortar exploded, stunning Sales. Some time later, feeling ‘very groggy’, he grabbed onto a log that had been part of a beach defense. A live mine was still attached to one end. Sales used the log as cover, pushing it in front of him, his face pressed to the wood. Finally, he got to the beach, where he spotted his boat’s communications sergeant, Dick Wright, who had jumped off after Zappacosta. He was badly wounded and had been washed ashore. When he saw Sales he managed to raise himself up on his elbows to tell him something but before he could utter a word a sniper hiding in rocks along the bluff shot him.

‘It looked like his head exploded,’ Sales recalled. ‘Pieces just fell about in the sand. And I lay there, just figuring I’d be next. I said to myself: ‘That sniper done and seen me, too.’ And evidently something distracted him, another boat maybe, a bigger target, because he didn’t get me. I buried my head in the sand as far as I could, put my arms over my head, and I just waited. I reckon I lay there thirty minutes.’

‘I’d seen a wall, maybe 150 feet away. I thought: ‘If I can get to that wall, I got a little protection. So maybe I can get another gun or some thing.’ I had fifty yards to go – a long way especially when you’re expecting a man to kill you. So I started using dead bodies. I would crawl to one and then real easy I’d move to another. That was the only protection.’

Sales inched forward. The corpses of Bedford boys and others dotted the beach, every ten yards or so. Some faces were familiar. They’d smiled at him across bars. They’d passed him on cold parade grounds. ‘I never seen a living soul from Company A that day,’ Bob told me. ‘But I saw their bodies. I don’t remember the names. I was so scared to death. But there were quite a few of them. It was definitely A Company I crawled around ‘ there was nobody else that could have been dead that quick.’

Sales saw another Company B man, Private Mack Smith, by a cluster of rocks at the base of the wall. Sales crawled over. He’d made it. Smith had been hit three times in the face. An eyeball lay on his cheek. Sales gave him a ‘morphine jab’, popped the eye back into the socket, and then bandaged him.

‘Them’s failed, man,’ said Smith. ‘We gotta get off this beach. They gotta send boats in for us.’

The pair stayed at the sea wall, both in shock, for what felt like an eternity. Sales would be taken off the beach that afternoon but would return before nightfall after persuading a doctor to allow him to rejoin a launch going back for wounded on Omaha. ‘There wasn’t a man off my boat who lived, except me. Not one.’

Sales fought on through Normandy. ‘D-Day was the longest day, there’s no doubt about that,’ he told me, ‘but for those who survived it was just one day. I had a hundred and eighty to go. I couldn’t begin to tell you how many men right beside me got killed. The average infantryman survived a week, if he was lucky.’

Sales told me every day was worse than the last, a gradual degradation of the mind, body and spirit. ‘You never got used to combat. Every damn morning, you got up wondering if you were going to live through the day.’

That last day took a long time coming. At 4am on 18 November 1944, Sales was ordered to take up position on the other side of a field before dawn. As he crossed the field, ‘the Germans lit it up with flares like you could play football on it and then opened up on us with tracer fire from a machine gun. When dawn came, I crawled back and then took a tank along a road. We got a German gun. I tapped the tank and hollered: ‘Okay! Let’s get out of here.’ The tank turned and then they hit us with an antitank rocket. There were balls of fire rolling out of my eyes. I couldn’t find my gun, nothing. I was hit in both eyes with shrapnel, blood was pouring out of my head from a cut, where my head hit the side of the tank. That finished me. I stayed in hospital a year and a half, lost an eye. The other one is not the best in the world but a hell of a lot better than nothing.’

Sales’ actions on 18 November earned him a Silver Star. Like so very many, he deserved far, far more. After the war, he became a successful businessman, working as a land developer and pulp wood dealer. He retired as the proud owner of his own company: the Sales and White Timber Company.

In 2014, he was one of six World War II veterans who were afforded the great honor of being made a knight of the Legion of Honor. To the day he died, he flew the Stars and Stripes at his home, was intensely proud of his fellow Virginians from the 116th Infantry regiment and indeed all of the 29ers who sacrificed so very much on D Day. 375 men from his regiment were lost on bloody Omaha. He had listed all the names of his buddies who died on D Day on the memorial he erected in his own backyard.

Sales never felt prouder to be a ‘Yank’ than that day in London April 1944 when he heard the siren call of a big band, perhaps the greatest of all time, and saw the English gals look his way.

And what about his proudest moment in combat, I had once asked him. What did he remember with greatest pride from his six months of fighting to liberate Europe?

‘I never killed a prisoner,’ he told me, deadly serious for once, ‘and I never sent one back when I thought a man would kill him.’

Thus spoke my greatest hero….. Goodbye Bob. I know you will rest in peace. None have deserved it more.

By Alex Kershaw for War History Online. Please LIKE Alex Kershaws Facebook page if you enjoyed his blog.

Buy The Bedford Boys on Amazon