This Dakota Hunter Blog features a photo album about one of the greatest military airlift operations of all time. In April 1942, the Allied Forces initiated an airborne supply line that crossed the Eastern Himalaya Mountain Range. This airlift supplied the Chinese War effort against Japan from India and Burma to the Kunming area and beyond.

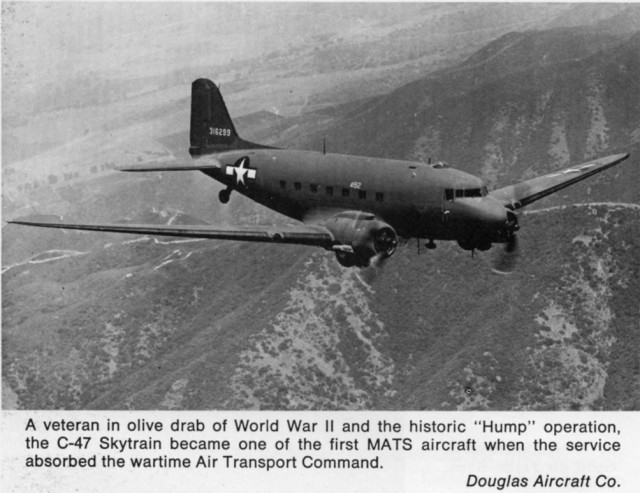

In this blog, I focus on the role of the C-46 Curtiss Commando and the DC-3/ C-47 Douglas Skytrain in the China- Burma- India Theater of War (CBI), also dubbed as the Hump operations. Other Cargo aircraft types that were also activated in this operation: the Douglas C-54 Skymaster, the Consolidated B-24 Liberator converted as a fuel transport C-109 and its Cargo version C-87 Liberator Express.

The US Government was very determined to keep China in the war and so put pressure on the Japanese Occupational Forces. The Allied Forces supplied the war effort of Chinese Nationalists first by road, later by air. They flew day-and-night missions from airfields in eastern India over the Himalayan Plateau known as the “Hump.” The 500‑mile air route to Kunming in China became known as the “aluminum trail”. More than 1,600 airmen and some 700 transport planes got lost in the mountains or in the jungles on either side of that huge hurdle. (Almost 1,200 men were fortunate to be rescued or walked out to safety.)

The high incident numbers were explained by the extreme altitude and weather of the Himalaya, and another factor was the duration of the Hump operations. From April 1942 until August 1945, 42 months of continuous and massive flight operations, the longest airlift in days of operations that ever existed so far and in numbers of tons of cargo transported only exceeded by the post-war Berlin Airlift (1948).

By July 1945, on average a whopping number of 332 airplanes a day flew over the Hump, a number five times bigger than the hard-pressed 62 aircraft on the route in January 1943. During its history, the Hump transport fleet carried 650,000 tons of gasoline, supplies, and men to China, more than half of that total in the first nine months of 1945. Imagine only the fuel that 332 flights per day would need to fly that 500 miles!

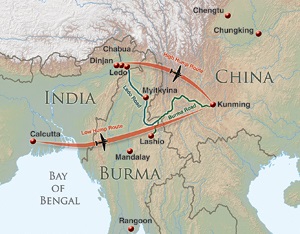

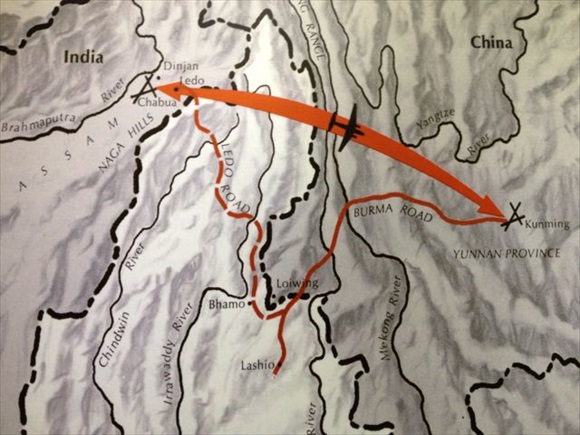

The Allied supply operations to support General Chiang Kai-shek’s Army that fought the Japanese Army in Eastern China, ran since 1938 via the supply road over the Himalaya from Bhamo and Lashio in Northern Burma into the Yunnan Province. This Burma Road was built just before the outbreak of WW II when the Sino-Japanese war started in that same year. The plan for a covert US supply of Military weapons, fuel and food to China dated from long before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and used that legendary winding & steep road with thousands of hairpins.

Part of that clandestine support to China also materialized in the famous American Volunteer Group (AVG) with their “Flying Tigers” Curtiss P-40 Warhawks. That daring initiative to fight the Japanese Imperial Army & Air Force in China with 100 pursuit aircraft and 300 American “volunteers” was masterminded by Claire L. Chennault, a retired USAAC officer, who had worked in China since 1937 as military aviation advisor to the Chinese Air Force and Army.

The AVG (later integrated into the USAAF) efforts needed crews, pursuit planes, fuel, food and spares. All that plus the huge supplies needed for the Chinese Army had to come over that single and most challenging Burma Road by truck! In spite of all setbacks of the extreme terrain, unpaved roads and adverse weather, it worked well. But that all changed dramatically as, on 8 May 1942, the Japanese invaded Burma and the main supply seaport Rangoon fell in their hands.

Allied access to that lifeline Burma Road was suddenly cut off. From that moment, it was decided to organize an airlift operation, running from NE India’s Assam Province town Dinjan with its airfield Chabua to the city Kunming in China’s Yunnan Province, in the region between the upper Mekong River and the Yangtze River. (see maps below, courtesy of http://ww2days.com )

Airlift operations over the Hump started in May 1942 with only 27 aircraft, mostly Douglas C‑47 Skytrains and 10 ex PANAM DC-3’s. The C‑47’s were gradually augmented by Curtiss C‑46 Commandos, with their stronger R-2800 turbocharged engines & more cargo space a better match for the extreme altitude flights. Air transports flew through mountain passes that were 14,000 ft high, flanked by peaks rising to 16,500 ft. Flying time was four to six hours, depending on the weather. The airlift ultimately operated from 13 bases in India. In China, there were six bases, with the main airport at Kunming, which became one of the busiest airports in the world with this unprecedented airlift operation.

It became a somewhat remote and forgotten war operation in this outback of the Highest Mountains in the World. Eastern India’s city Calcutta was since April 1942 the seaport, from where all goods had to be shipped in from overseas. A logitical nightmare had to be resolved to get the goods from Calcutta up north to Chabua Airport. By train turned out to be a disaster with the overload of a poorly functioning railroad infrastructure, so soon yet another air bridge was created between Calcutta and Chabua in the North.

Only the “second stage” airlift brought all goods to Kunming. For the transport of fuel, the converted B-24 Liberator (designated C-109) was able to fly non-stop from Calcutta directly to Kunming over the ‘Low Hump route” more to the south. This route was frequently patrolled by the Burma-based Zero Fighters.

Allied aircraft became more vulnerable due to occasional confrontations with the Japanese fighters. You wouldn’t feel very comfy flying there in an aircraft, filled to the brim with a flammable cargo, consisting of High Octane fuel. The sight of a Zero on the horizon must have been a scary experience, the crew realizing that even the accidental hit of a single stray bullet from that Zero could mean the end. The US Air Transport Command ATC acronym was sometimes jokingly dubbed as “Allergic to Combat” but such disdain was far from the reality of the nature of the ferry flights over the Hump.

Military commanders considered flights over the Hump to be more hazardous than bombing missions over Europe! For its efforts and sacrifices, the India-China Wing of the Air Transport Command was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation on January 29, 1944; the first such award made to a non-combat organization!

Photo above; the original caption that comes with this photo seems erratic. A marvelous photo, but more likely French Colonial than Chinese Troops that start boarding the C-46. It could have been taken in WWII or taken just after the war, as the USAAF/ USAF gave support to the French Army in Indo-China, where a communist guerilla started that would finally lead to the defeat of the French Army in Dien Bien Phu (1954), Vietnam. If you have any better clue, let me know.The US Stars & Bars on the aircraft without the red “middle lines” mean that this photo was taken before January 1947.(photo courtesy www.c141heaven.info)

Photo above: Fueling a CNAC C-47 ar Suifu, China (photo dated 12 November 1944 , courtesy www.cnac.org ). The pilots carried the 55 gallons fuel drums with them over the Hump on the way out so to have enough fuel to make it back home again. The refueling was awkward, first poured in the square 5 gallons cans, carried up the ladder and poured into the wing tanks. Note the CNAC roundel on the C-47 in the backdrop. Those aircraft all belonged to the China National Aviation Corporation, co-owned by Pan American Airways with a majority stake by the Chinese Government.

Throughout the war, the CNAC flights remained intact and were integrated into the total airlift operations between India and China, with American crews, accountable for 10 % of all cargo transported during the Hump Operations. Today , the name CNAC still exists as the Chinese State-owned Aviation Holding Company, owners of Air China and Air Macau.

Photo above shows the loading of a small US Army airplane, being pushed inside the cabin of a C-46. Those were Taylorcaft made O-57Grasshoppers/ L-5 Sentinel light observation & liaison planes used for the spotting of lost airplanes and rescue pickups of downed or parachuted crews. Former test pilot Capt. John L. Porter’s team was accounted for every crewman recovered in 1943. He had for his unit also a small number of C-47’s and 2 B-25 Mitchells, that could parachute medics into crash sites to aid injured crewmen. Porter got killed as his B-25 was attacked by Zero fighters during an SAR mission in December 1943 while trying to return to his base in Chabua , India.

The three photos above and below give a good impression of the loading capability of the C-46 Curtiss Commando. Its payload of 15.000 lb (6.800 kilos) was more than double that of the C-47 payload (3000 kilos). Its cargo doors were higher and wider and allowed for better access of vehicles. With a higher ground clearance, the entry needed a special double ramp as you can see in the photos. 3 Jeeps plus 30+ soldiers was a standard load for the rugged C-46.

The Curtiss Commando C-46 made it on the cover of LIFE Magazine, but its initial career was seriously hampered by all sorts of problems after its maiden flight in 1940. DC-3’s Maiden flight was on 17 December 1935 and within 6 months it was operational, but with the C-46, it took almost 2 years more to iron out all the Gremlins.

A major step forward was the mounting of the Pratt & Whitney radial R-2800 engines of 2100 hp each, cranking out 900 hp more per engine than its smaller competitor C-47. But the C-47 had a long pre-war career (as the passenger transport DC-3) that had made her more reliable in the often primitive wartime conditions of engine maintenance and flight operations. The C-46 remained the somewhat capricious aircraft, with 2 nasty habits: persistent hydraulic leaks and worse, the long time not well-resolved fuel leaks that allegedly could have caused in rare cases mid-air explosions of the aircraft.

Both aircraft were obsolete by the end of the war and production of both aircraft was canceled or continued only for a short time from surplus spare parts. For the DC-3/ C-47, the Mfg. counter ended at just over 10.600 aircraft produced in USA while the total production of the C-46 ended at just over 3.100. The war surplus aircraft of both types went straight into the post-war civil and military market, whereby the C-47 was the better match for passenger transport. The refurbished C-47 , converted to the DC-3 configuration, was extensively used all over the World in the rapidly emerging scheduled passenger air transport and the tourist flight market in Northern Europe to fly to the sunny beaches of Spain, Italy, Canary Islands etc..

Photo above (courtesy MIArecoveries.org) depicts a crashed C-47 in the Himalaya Mountains. Allegedly, there are still over 500 wrecks scattered around the routes that they flew over the Hump during WW II. It became for many the “Skyway to Hell”. 1200 crewmembers are reported as still missing here and the US Government undertakes steps to soon start the search and recovery of its servicemen lost, now over 70 years ago in the world’s most inhospitable terrain.

After the war, the Curtiss Commando went in use in much smaller numbers than the DC-3, mainly in the Americas. Some 8 years ago, I found the aircraft still operational in Anchorage, AK as I visited the premises of Everts Air Cargo (the C-46 named “Maid in Japan”) and in Fairbanks with Roger Brooks Air Cargo and later met Joe McBryan in Red Deer, Alberta, from TV fame with his Buffalo Airways. But the best memories of this aircraft come from my expeditions in Bolivia, where I made many flights over the High Andes in a real worn & torn C-46 Meat Hauler reg. nr. CP-1319.

In that aircraft, I was the guest of the “Mad Pilot of the Andes”. The Mucho Macho dude flew me from El Alto Airport/ La Paz over the Cordillera Mountain Range to the Northern Jungle Ranchos of the Beni and to Lake Titicaca (see photo below). We passed mountain peaks and altiplanos of similar heights as the “High Hump Flight” route. I suffered from a lack of oxygen, terrible cold and had attacks of panic and claustrophobia, as I never had before. If you want to see more of my stunning flight experience in a C-46, click the start button in the picture below and enjoy the view of an ultra-low fly pass and the roaring sound of those mighty R-2800 radial engines.

For more tales and photos of my eventful experiences with vintage aircraft, you should read my engagingly written book The Dakota Hunter (Casemate Publishers USA/ UK, 320 adventure-packed pages illustrated with 250 photos). You can order it via my website, click here for more details about my book. Or go directly to Amazon for instant online ordering and 5-star reviews by clicking here at Amazon direct order link.

Best, Hans Wiesman