War History Online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Ricky Phillips.

The 1982 Falklands War is, for its brevity – at just 74 days – one of the most widely studied, and written and conjectured about, wars in history. The reason for this conjecture seems to be that between the two protagonists, Great Britain and Argentina, there is almost nothing in the war that the two sides can agree upon, including the name of the place.

Yet there has to be a reason for so many conjectures and myths, which we find right at the very start of the war itself. We read how “Thatcher started the war” as opposed to it coming “out of the blue” as she herself said, and the seemingly unending myths, rumors and theories abound from there.

The episode which was to crown all of this was, of course, the Argentine invasion on April 2. More recently, only in the last couple of years, the world has begun to learn of the battle of Stanley, a battle which the governments of the U.K. and Argentina both downplayed as the merest skirmish, for very different reasons.

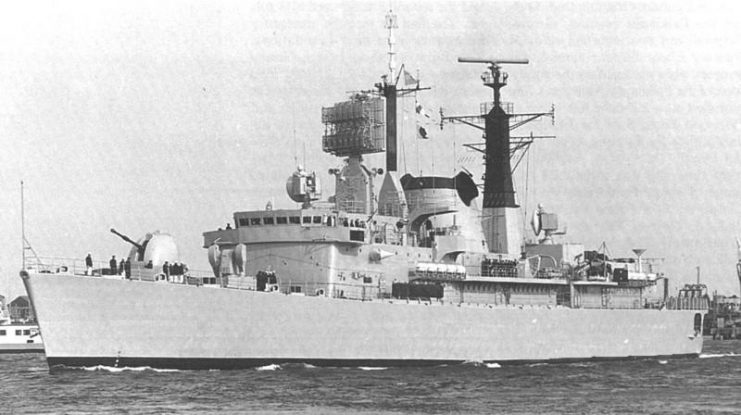

The British government was neither blind nor deaf to the Argentine threat to the Falklands and had been given countless warnings of the impending invasion. It seemingly did nothing, but this is not the case. On March 2 the British Defense Attache in Buenos Aires wrote to Rex Hunt, the Falklands’ Governor, copying in both the MOD and the FCO with growing concerns of the Argentine threat of invasion.

He felt so concerned that the following day, the memo reached Margaret Thatcher with additional notes, highlighting not only that an invasion was coming, but also even roughly when it would occur. Scrawled across this memo in the Iron Lady’s own handwriting were her own thoughts on the matter: “We must make contingency plans.”

Prima facie, nothing seemed to change in the Falklands, where one 44-man detachment was preparing to go home after a year’s tour in the Falklands and was about to be relieved by another, yet there were strange happenings towards the end of March. Camouflaged men were seen moving by night and evidence of their passing was noted by a number of Falkland Islanders.

A garbled message intercepted from U.S. Intelligence spoke of a submarine landing to the south of Stanley, and a Royal Marines Corporal sent in a report of a nuclear submarine which he had witnessed surface just off the coast. These reports were sent in–and seemingly ignored.

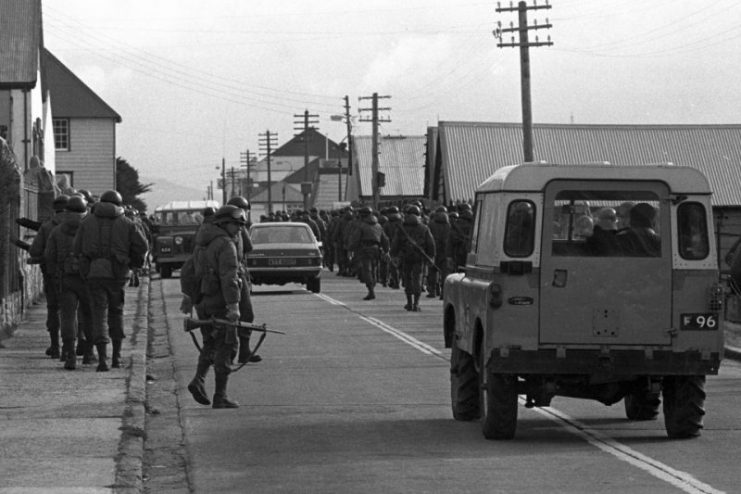

On the day of the Argentine invasion, the 69 Royal Marines and Royal Navy men present put up a fight not seen since Jadotville in 1961. Against all odds and with only one outcome, they battled through the streets of Stanley and in the windswept plains around the town.

An Argentine landing craft with forty men was hit with an anti-tank rocket and flipped over, taking all to the bottom. An LVTP-7 armored personnel carrier was struck with three anti-tank rockets, causing carnage among the 28-man crew and passengers of which, the Argentines themselves admitted, only a few escaped alive.

Another such vehicle was hammered with machine gun fire, smashing its gunner’s scope and badly damaging the vehicle. At Government House, from behind a stone wall, the Royal Marines battled waves of attackers.

Their top sniper, Geordie Gill, considered one of the best in the Corp’s history, brought down one after another of the attackers, finishing by dueling with a half-inch machine gun against his bolt-action sniper rifle until the machine gunner too fell dead.

All around were killed and wounded Argentines and still, no British were so much as wounded, After receiving veiled threats to bombard the town from the Argentines, Rex Hunt agreed to order a ceasefire. In his memoirs, Hunt recalled watching two full body bags being hauled across his wife Mavis’ rockery as the doctors and nurses from the hospital came out to retrieve the many killed and wounded men.

Some of Hunt’s descriptions were quite graphic. It had been an epic battle in which the Royal Marines knew they had upheld the best traditions of the corps and given their best, almost until the last bullet.

Major Mike Norman’s official report listed very conservative figures of only the Argentine casualties they had absolutely seen: 5 killed, 17 wounded, 3 prisoners and 1 Amtrac APC destroyed.

The staff at Stanley’s only hospital treated scores of men in what they described as the busiest 48 hours of their lives, and even MI6 picked up reports sent back from the islands by Argentina reporting “Dozens of dead”–yet these reports were hidden away in secret files. Major Norman’s own report, the earliest to be released, was not released until 2012.

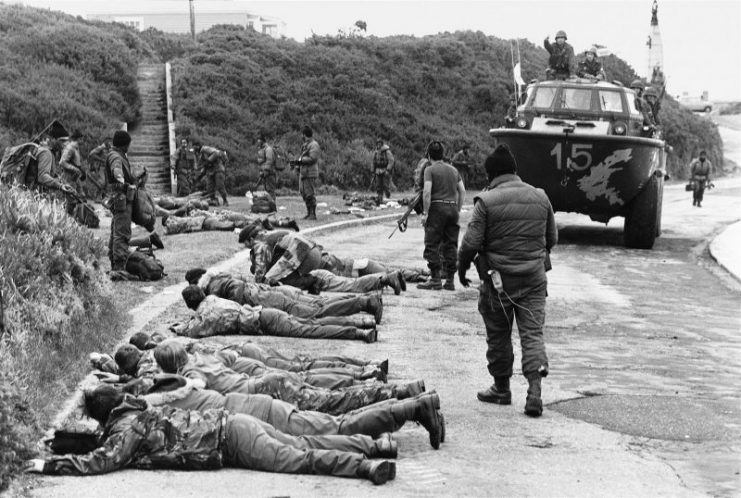

When the Royal Marines returned home, they were treated to newspaper headlines of “Shamed” and “Surrender,” and one article suggested that they had given in “with barely a shot fired.” Their own story had been buried and replaced with junta propaganda of an almost bloodless victory, with but one Argentine killed and three more wounded.

The impression given was that the Royal Marines had been left there to die, so that an outraged western world would be on the side of the U.K. When that outrage hadn’t happened, the Argentine “Shameful surrender myth” had been quickly borrowed and even enlarged, with photos of the Marines laid in the road with black-clad assailants standing over them–the very image of a fascist junta stomping on freedom. That story worked.

The Argentine story quickly became the only story, but even then, the Argentines questioned who the extra men were whom they had seen and fought, which could not have been the men of the Royal Marines. The Royal Marines themselves questioned who had blown up and sunk the Argentine landing craft after it was dragged up from the harbor with a gaping hole in the side. Someone else had been there and had ensured that the Argentines would fight to the finish.

Margaret Thatcher had indeed made “contingency plans” and it is now known that British submarines had watched the invasion happen and that SBS operatives had engaged the Argentine forces and even sunk their landing craft. A prepared Britain could not look like the injured party, however, so the Argentine story was allowed to prevail over the true one of Britain’s own great defenses against overwhelming odds, in order to guarantee the right international reaction. The British plan worked.

Read another story from us: Argentine Air Force Pilots in the Falklands

In Parliament, the question that had been asked of Lord Franks was asked a second time of the Prime Minister–whether she had “lured the Argentines onto the punch.” The Prime Minister did not answer, and for 36 years, 69 brave heroes took the blame for political mismanagement which set Britain on a reactionary course, first to war, and second to a reversal of back-stepping policy. In truth, the country as a whole owes the brave Royal Marines of NP8901 everything it has today.