Thanks go to Marty Morgan for this wonderful article.

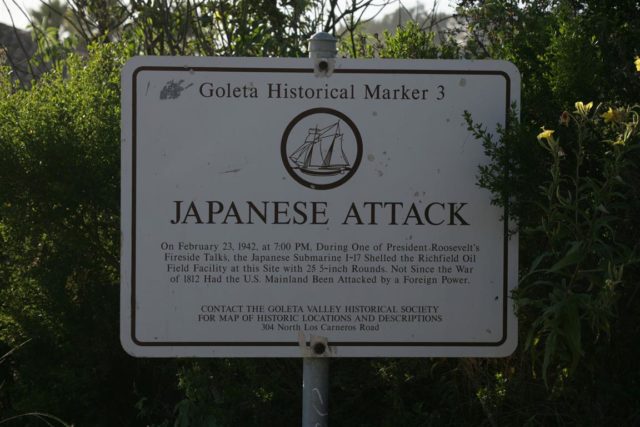

Two months after Pearl Harbor, World War II raged around the world in places like the Philippines and North Africa. Though Axis forces marched unchallenged across large parts of Europe and Asia, North America remained untouched by aggression. But then the enemy struck his first blow against the continental United States. Just after 7 p.m. on February 23, 1942, the Japanese submarine I-17 surfaced off the California coast just west of the town of Goleta. Using its deck guns, I-17 proceeded to shell the seaside refining facilities of the Elwood oil fields in an incident that triggered panic throughout the state and aroused questions about the security of American shores.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose the 210th anniversary of George Washington’s birthday to address the American people with his first Fireside Chat since Pearl Harbor. The address began at 10 p.m. Washington time – Monday, February 23, 1942 – and was broadcast on every major radio station around the country. Early on in the speech, Roosevelt characterized the conflict that the United Sates had entered only two months earlier as “a new kind of war” that was “different from all other wars of the past, not only in its methods and weapons but also in geography.”

The president then described this new war as “warfare in terms of every continent, every island, every sea, every air-lane in the world.” At that point, he asked his listeners to refer to a world map as he spoke so that they could better understand the vast geography associated with the intensifying Second World War. The president then made a prophetic statement: “The broad oceans which have been heralded in the past as our protection from attack have become endless battlefields on which we are constantly being challenged by our enemies.”

At the exact moment that President Roosevelt uttered those words a Japanese submarine surfaced just off the U.S. west coast. The sub was the I-17 and her captain, Commander Nishino Kozo, steered her into the Santa Barbara Channel – the body of water that is bracketed by the mainland of California on one side and the Channel Islands of San Miguel, Santa Rosa and Santa Cruz on the other. The enemy submarine proceeded in a southerly direction along the coast to a spot just west of the town of Goleta, at which point crewmen assembled on deck and prepared the sub’s two 5.5-inch (14cm) guns for firing.

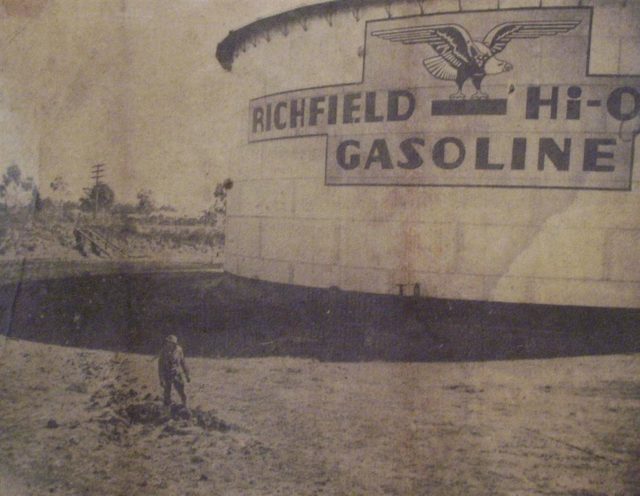

Their target was the Elwood Oil Fields, an area about 12 miles west of Santa Barbara where two companies – Richfield Oil and Bankline Oil – were operating drilling, refining and pumping facilities along an otherwise deserted stretch of bluffs on the western outskirts of the town of Goleta. As the sun began to set, Commander Kozo gave his gunners the order to open fire and one of the sailors on the forward gun pulled the lanyard, sending a projectile streaking toward the refinery. The time was 7:18 p.m. and at Wheeler’s Inn Hilda Wheeler was in the kitchen washing the dishes from dinner. When she heard an unusual screeching sound she rushed to her window to find out what was causing it and was surprised to see “shells tearing up the ground” as they landed between the inn and the oceanfront. When Mrs. Wheeler’s husband Lawrence heard the sound, he rushed outside just in time to see a shell explode against the bluff about a quarter of a mile down the beach. Mr. Wheeler then watched as another shell “whined” overhead and landed in a canyon on the other side of the beach road near the home of the Staniff family. The shell dug a hole five feet deep, but failed to explode. Inside that house, Estelle Staniff and her friend Jo Thompson were at first “scared to death” by it but then assumed that the military was conducting target practice.

At about that same time, Mrs. George Heaney picked up the telephone in her house in nearby San Marcos Pass, dialed the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Department and frantically reported what was happening. Using a pair of her husband’s field glasses, she could see a submarine lying about a mile offshore firing at the refinery. A second call came in shortly thereafter from Bob Miller at the Bankline Oil Company facility. With shells shrieking overhead, Miller described the same submarine that Mrs. Heaney had only moments before. Inside the refinery, oil worker Gerald O. Brown and the 30 other workers on his crew dropped what they were doing and hastily fled the facility. When he got outside and could see the enemy vessel, Brown first thought that it was a cruiser because it was so large.

For over 20 minutes, I-17 hurled round after round at the shore with accuracy that varied wildly. Eleven of the shells were apparently short rounds that exploded harmlessly in Santa Barbara Channel and one reportedly overshot the target by almost three miles and landed on the Tecolote Ranch. Commander Kozo’s Gunners ultimately found their range though and put several shells in the target area. I-17’s fire was directed at two particular points within the facility: the drilling derricks that were connected to the shore by wooden piers and the huge oil storage tanks at the refinery terminal. Of the shots fired at the storage tanks, most fell short and exploded against the face of the seaside bluff. Only one landed on top of the bluff, but it was a near miss that did little. That shell landed only a few feet away from one of the tanks producing a crater as big as a Jeep. Some of the fragments thrown by the blast slightly damaged a nearby 14-inch pipeline and others dented the outer wall of the closest tank. The only direct hit that the Japanese registered that night was against one of Bankline’s piers. That shell punched through the platform’s wooden pier at the base of one of the drilling derricks and then exploded in a pump house.

After 20 minutes of continuous bombardment, I-17 ceased fire and left the area at 7:35 p.m. About an hour later, the Rev. Arthur Basham of Montecito reported the submarine exiting the south end of Santa Barbara Channel moving in the direction of the city of Los Angeles. According to some sources, I-17 had fired only 16 times during the attack. Others say that the number was actually 25. Whatever the case, the damage to the refinery terminal was negligible. The direct hit that wounded the Bankline drilling derrick pier and pump house was repaired before the end of the week for a mere $500. Though the injury may have been slight, I-17 had proven President Roosevelt’s words even as he was speaking them. The last time that the shores of the continental United States of America had been attacked by the naval forces of a foreign enemy had been in February 1815 when the British assaulted Fort Bowyer on Mobile Bay, Alabama at the conclusion of the War of 1812. For 127 years the “broad oceans” had indeed insulated the country from attack. But as I-17 had demonstrated that February evening, those same oceans were the new “endless battlefields” that the enemy could use to threaten the national security of the United States.

Though I-17’s attack on the refinery facilities at Goleta was relatively insignificant in the overall history of the Second World War, the war hysteria that resulted from the episode was by contrast of great significance. A mere 23 minutes after I-17 fired its final shell, the Army’s Fourth Interceptor Command ordered all radio stations in southern California to cease broadcasting. Shortly thereafter, a mandatory blackout was ordered for the 25 miles of coast stretching from Goleta south to Carpinteria and the city of Los Angeles was placed on alert. Experiencing such precautions for the first time, the civilian population knew that something serious was happening. Hundreds of phone calls immediately began flooding the switchboards of police departments throughout the affected area. Concerned citizens wanted to know what had happened and what they should do. Operators reminded the callers that the first rule during an alert was not to use the telephone. Other callers reported seeing yellow flares over the coast in Ventura County near Hueneme and one report even claimed that two suspicious individuals were at the end of the pier at Venice Beach near Los Angeles using flashlights to communicate with an unseen vessel offshore. In each case, police officers were dispatched to the scene only to find that the reports were false.

The story of the attack was reported as front-page news in both the Los Angeles Examiner and the Los Angeles Times. The public also learned about what happened through radio news reports that were broadcast throughout California the following day. These reports generated nervousness among the military and the general population that would lead to one of the more unusual incidents to take place on the home front during World War II. Before dawn on Wednesday, February 25, 1942, the coastal areas of the entire state remained under alert and at 2:15 a.m. defenders in and around Los Angeles were informed that an air raid could be expected at any time. Reports of approaching aircraft soon followed and then at 3:06 a.m. anti-aircraft batteries near Santa Monica opened fire. The firing continued sporadically until dawn, by which time almost 1,500 rounds of ammunition had been expended against enemy bombers that were not really there. The incident is remembered as “The Battle of Los Angeles” and it was the sum of a sequence of events that began with I-17’s shelling of the Elwood Oil Fields.

Author: Marty Morgan