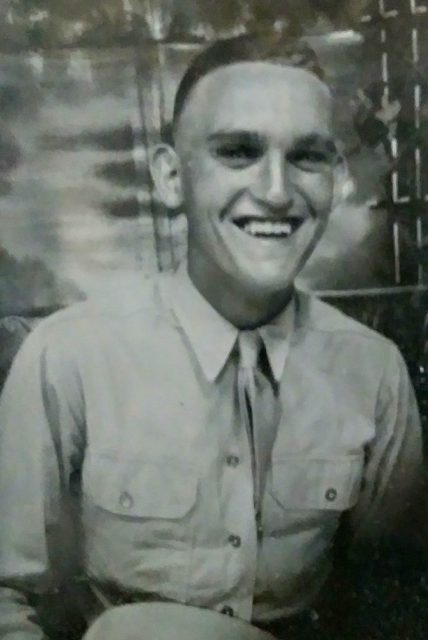

In the late spring of 1944, Lloyd Workman left his home near the community of Vienna, Missouri, to travel to the sprawling city of St. Louis, where he was able to acquire employment with the Goodrich Tire Company. It was simply a period of waiting, he explained, since he realized the long tentacles of the military draft of World War II would soon reach him.

“I got my notice for a draft physical in the mail and was sent to Jefferson Barracks in August of 1944,” he recalled, adding, “It wasn’t but a few days and I was inducted into the U.S. Army and sent to Camp Fannin, Texas, for training.”

Located near Tyler, Texas, the former Camp Fannin served as an infantry replacement training center during WWII. During his 17 weeks there, Workman said, he participated in a 20-mile “march with a full field pack,” in addition to receiving an introduction to machine guns.

“We trained with the A4 and A6 [variants of a .30 caliber Browning machine gun] during our training cycle,” he explained. “As the gunner, I carried the machine gun and I had an assistant gunner that carried the tripod and the ammunition.”

When his initial training was completed, Workman returned home for several days of leave before reporting to Ft. Meade, Maryland, in the early days of January 1945. From there, he was sent to Camp Shanks, New York, to board a British troopship that carried him and other replacement soldiers to Liverpool, England.

Eventually, the veteran explained, he was sent by train to the port city of Southampton and ferried across the English Channel to France. Following additional rides by train and military truck, the young soldier arrived in Metz, France, and was assigned to Company C, 22nd Infantry Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division.

“The Battle of the Bulge had recently ended and they gave me a machine gun right off the bat,” he said. “At one point, we were in a pillbox on the Siegfried Line and became pinned down by German machine gun fire. My assistant gunner was 15 feet from me but couldn’t get the tripod over so I could return fire.”

Workman explained that another platoon on his flank was able to “take care” of the enemy attack. Shortly after this event, the young soldier asked his platoon leader to give him a Browning A6 machine gun since it could be fired by one person and he would not be dependent on the tripod carried by an assistant gunner.

Although his request was granted, it was not long after this event that he was introduced to the range of threats that can emerge in a combat zone.

“We were on the move one morning at about daylight, at the time of day when there’s really not enough light to make anything out,” he said. “A guy to the left of me from another platoon stepped on a Bouncing Betty [German mine], I believe, and when it exploded, a piece of the shrapnel hit me in my leg.”

The veteran described hearing the unknown soldier calling for a medic to come provide emergency medical care. Workman and his fellow soldiers continued forward on their mission, and it was not until some time later that his own injury, though minor, was reported to medical personnel.

For the injury, Workman was later presented a Purple Heart. This was not the only medal he would receive. He was provided an opportunity to demonstrate his mettle in combat several weeks later, during an event that resulted in his receiving the nation’s third highest military combat decoration.

On April 3, 1945, after his company had been surrounded by enemy forces, “Private Workman seized his assault machine gun and ran forward of the company lines to repel the enemy force. Time and time again he held the enemy at bay…until mortar fire could be adjusted upon them,” wrote Major General George P. Hays in the citation for the Silver Star that Workman was awarded.

The 4th Infantry Division continued fighting toward Germany and, after reaching the Rhine River, were relieved by the 11th Army. The division moved south and when the war in Europe came to an end on May 8, 1945, Workman believes they were “somewhere near” the borders of Austria and Czechoslovakia.

“I was one of the first from our company sent home after the war because they planned on sending me on to fight in the Pacific,” Workman recalled. “But there was a huge public outcry over that practice and my orders were changed for Camp Butner, North Carolina, where the division was inactivated.”

The combat veteran was eventually transferred to Ft. Benning, Georgia, spending the remaining months of his military commitment helping to train officer candidates. On July 5, 1946, he received his discharge from the U.S. Army at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas.

After returning to Missouri, Workman married, raised two daughters and completed a lengthy career with the Carpenters Union. Though decades have passed, he views his experiences in WWII as an obligation that he was able to survive and remain in good health.

“I didn’t have any choice since I was drafted like so many others, but I’m glad that I did it,” he affirmed. “I’ve been told that I was lucky…and I was. I could have been hurt a lot worse.”

He added, “I learned to take orders, to do what I was told, and I got to come home when a lot of guys never did.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.