War History Online Presents a Guest Blog from the essayist Pietro Giovanni Liuzzi

Very often we come across dramatic events that seem to exist only in the film plots even if these are taken from reality.

The story that marks the first meeting, after 70 years, of two Italian brothers who, presaging the existence of their kinsman in Greece, began the concretized search when the main protagonists had already died.

Vincenzo was an artillery sergeant serving in Coo in 1943. He spent his military period at Antimachia (Antimaheia) airport. Life was quiet because the war winds were still far enough away.

Like many other conscripts, in his free time from the service, Vincenzo went to a local Greek family of shepherds and offered them help where he could in exchange for the family warmth that so much lacked due to the distance from his loved ones.

In the family there were three children: Nicolaj, Dimitris and Katerina (Katerigno). With the latter, an affectionate relationship bloomed.

Then came the Italian-Anglo-American armistice that shattered the peaceful life not only on the island but throughout Italy and the overseas occupation territory. The sudden joy of the military, in particular, at the news of the suspension of hostilities was replaced by concern of the German retaliation that was immediate.

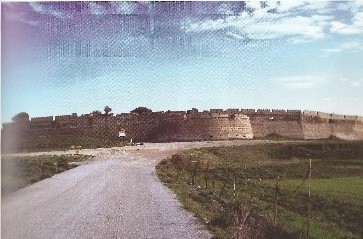

Heavy bombings began on the island by the Luftwaffe, an omen of an imminent attack. The British Intelligence signaled the impossibility of the Germans to carry out naval landings due to the lack of vessels of any kind; the attack would have come only with paratroop launchings. In fact, Italian and British troops, who arrived on the island together with an Indian labour unit after September 8, 1943, were advised to move away from the positions during the air strikes.

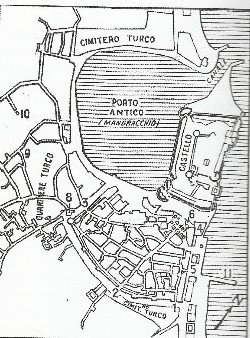

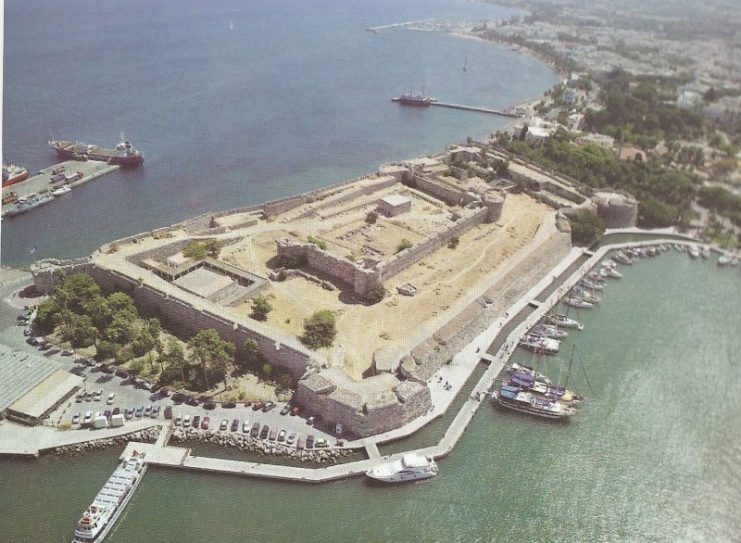

So, in spite of the information received, on 3 October, at 3 o’clock in the morning, a German convoy formed by different type of craft, including five steamers requisitioned to the Italians, cast anchors between the islands of Calimnos and Pserimos, just 3/4 miles away from the north coast of Cos.

The landing started. The commands of the defending troops were taken aback. Although the danger of an invasion had been given promptly, quickly and insistently by the sentinels along the coast, the island alarm was issued with considerable delay. In 34 hours of more or less intense fighting the island was occupied.

The Antimachia airport was attacked by paratroopers and special troops arriving by sea. Resistance was almost non-existent. The Italian and English troops dispersed among the badlands of the area; they escaped by taking refuge in the caves and reaching the hills not far away. The British moved away thanks to the naval craft made available to them by the Cairo command.

Vincenzo followed the fate of his companions. He escaped to avoid capture and joined the Greek family who had him hiding in a nearby cave. Caterigno’s father brought him food before the family was forced to move away from the area with their cattle and take to the hills to prevent the Germans from seizing all they possessed. It was since then that Vincenzo remained without sustenance. He went out into the open to find something to eat but ran into a German patrol that captured him.

First to the Castle in the city, then to the port for boarding and then, after a long voyage, huddled in the bowels of the ship and treated worse than livestock, reached with the other prisoners Piraeus and, from here, the railway station where he was forced to embark on a cattle wagon. After days of exhausting travel, the train arrived in Berlin. The prisoners were taken to the Spandau concentration camp in Stalag III D.

In April 1945 the Russians released the prisoners. Free of sentinels and, therefore, of control, the men could enter and leave the railway station. Vincenzo learned of a train leaving for Greece. Despite the opposition of an officer he could embark because he said he wanted to reach his family in Greece. In fact, Vincenzo, although he was already married in Italy and had children, was willing to return to Cos.

Once again the journey was exhausting, but the satisfaction of being able to return to a friendly land, any symptoms of tiredness had vanished. The train arrived in Thessaloniki. The soldiers were taken off the wagons and sent to a ship leaving for the Dodecanese. Vincenzo went along with the others but an English officer, this time, forced him to take the ship that left for Italy.

He thus had the opportunity to rejoin his original family but in his heart, he always had the impressive memory of the young Greek he had to leave.

Years later, the son of Vincenzo, Fortunato, a retired police inspector, perhaps because of his long habit of finding the “guilty”, decided to find out why his father very often was repeating an almost uncomprehensible word “Savas”. He remembered that peeking through his father’s personal things, he had found a letter from Greece with a picture of a woman and a girl.

In time, Fortunato tried to get his father to talk about the past until one day he secretly installed a camera and asked his father to tell. Vincenzo repeated the story described until the day he arrived in Thessaloniki where he was forced to embark for Italy.

Fortunato, after the death of his father, now retired, decided to get to the bottom of the photo of that child depicted in the snapshot and why his father wanted to return to Greece.

Having learned of the book (“Kos, una tragedia dimenticatas – Cos, a forgotten tragedy”, today in English under the title “Events on Cos”) Fortunato phoned the author to ask him if he knew someone on the island suitable for researching people.

The help was offered to him and, thanks to the intervention of a Greek historical officer of the island who lives in Kardamena, near Antimachia, after a few days it was known of the existence of a certain Popi Savas born on 12 December 1943 who claimed to be the daughter of an Italian soldier whose name she knew, Andrea and his origin region in Italy, Molise.

With the exception of the name, Andrea instead of Vincenzo, the known data gave a chance to believe that she was the person sought. Despite the opposition in the family, Fortunato’s police nose got the better of him.

A meeting was organized and in October 2013, on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the slaughter of Italian officers by the Germans for which a solemn celebration was taking place, two Italian brothers, and their wives went to Cos to meet their possible sister.

There was a long interview. The doubt remained because of the mismatch of the name that could be interpreted with Vincenzo not to provide his real name because he had been ordered or wished to maintain a non-true identity or liked to call himself Andrea. The first hypothesis was unlikely because in those years the Italian Authorities wished for a broader integration for the Italianisation of the overseas Province.

The hotel that hosted the meeting seemed a theatre stage. Everyone, hotel staff and guests, were experiencing a moment of great emotional and, certainly, historical tension. Everyone was amazed knowing the epilogue of a war happening.

The meeting was partially positive because one of the brothers was skeptical about recognition. Fortunato, however, immediately felt the bond of blood that existed between them: the resemblance between the photos of their father and the Greek woman. DNA testing was arranged to dispel any doubt. Result: 67% compatibility. It was a sign of consanguinity and that, even if it is distant from 100%, it should be considered valid because it refers only to one of the two parents. Among other things, there was absolutely no extraneousness between the stocks. She was their sister and the fact was incontrovertible.

What emerged from this story. Kalliopi (Popi), the young Greek had lived a grim life. Her mother, who died a few months before the meeting at Cos, had waited a few years for Vincenzo’s return; then she went to marry a man with whom she had two children. The inhabitants of Antimachia mocked Popi and pointed her out as the daughter of no one. But now she knew who her natural father was and had finally met the brothers so she could feel accepted. The television and local newspapers gave great evidence to that story and to the consequent meeting.

If this story had surfaced a few months before, Vincenzo could have met Catrigno, whom he had never forgotten, and Popi, whose photograph he jealously kept.

Fortunato has published a book about the whole affair which is now in the public domain. Also in Italy, the national television has recently dealt with the happy story. Fortunato, repeatedly, expressed his thanks to his Greek mate Jannis, a professor at Cos, who has acted as an interpreter and advisor as only a conscientious and loyal friend can do.