War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

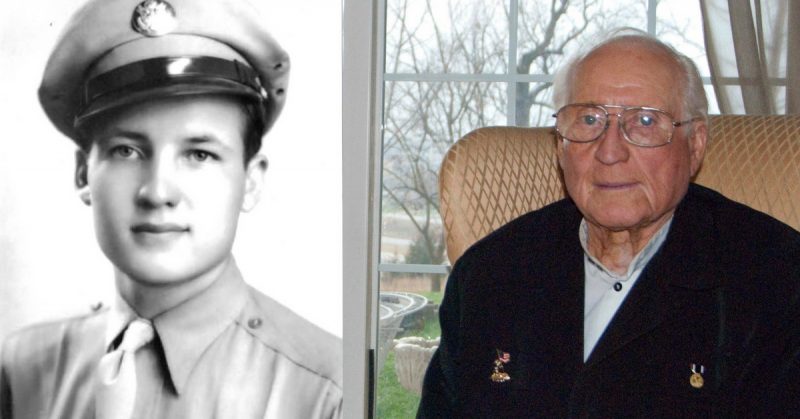

With a sense of duty and patriotism signifying the character of those coming of age during World War II, Missouri resident Ralph Kalberloh was honored to answer the call to service during a time of war. And despite circumstances which later found him detained in an enemy prison camp, Kalberloh asserts his experiences have granted him a unique perspective on the true costs of freedom.

“During the (Second World War), I probably could have gotten a farm deferment, but at that time no one wanted to avoid the war,” said Kalberloh.

Growing up on a farm near the rural community of Hardin, Mo., Kalberloh left high school following his junior year to enlist in the United States Army Air Forces—much to the disappointment of his mother.

The veteran recalls, “I knew I would be drafted…and I thought it would be better to fly than to walk and sleep in a foxhole.”

Inducted into service in September 1943, Kalberloh began his cadet training in Amarillo, Tex. Completing several months of training, he was then assigned to a B-17 Bomber crew as a tailgunner.

Recalling the uncomfortable nature of the task to which he was assigned, Kaberloh noted: “(As a tail gunner) You were in a small area in the rear of the plane for sometimes eight hours—or however long the mission lasted—on your knees sitting on something similiar to a bicycle seat.”

“Looking back, I don’t know how I endured that,” Kalberloh quipped.

Kalberloh’s newly-formed crew was soon transferred to Lincoln, Neb., where they picked up a new B-17 and received orders to deploy overseas.

Leaving Nebraska in December of 1944, they flew the plane to Wales following several refueling stops.

Upon their arrival, the new plane was taken and assigned to another crew, while Kalberloh’s group was provided with one that had recently undergone repairs after receiving significant damage during a previous air skirmish.

“The ground crew chief told us to take care of the plane we had been given as a replacement since it had just been fixed up,” Kalberloh said. “It was shot down on our first mission…so I guess he wasn’t very happy with us.”

Named “Dixie’s Delight” in honor of the only whiskey the crew could seem to acquire during the war, the plane began taking flak while bombing targets near Berlin on February 3, 1945.

The aircraft eventually sustained enough damage from anti-aircraft guns that the pilot gave the order for the crew to evacuate.

Jumping from the plane along with eight of his fellow crewmembers, Kalberloh’s parachute became entwined in a tree. The cords on the chute then snapped and he injured his back when he fell to the ground.

Separated from his fellow crewmembers, Kalberloh roamed the German countryside for the next five days without food, maps or money, trying to evade capture. He eventually succumbed to his hunger and—on February 8, 1945—surrendered himself to a German farmer who fed him before turning him over to the town marshal.

The young prisoner was intially interviewed by a Gestapo officer before being sent to Frankfurt for further questioning. In Frankfurt, he was interrogated by an American defector originally from Chicago, but serving as a colonel with the German Luftwaffe (Air Force).

His captors sent him to a POW distribution center in Wetzler, Germany, then on to a prison camp at Nuremburg. While in prison, he survived on a daily ration consisting of a loaf of bread containing 10 percent tree flower (sawdust) and shared amongst seven of his fellow prisoners, a can of watery soup, and an occasional Red Cross parcel.

“I was just a 19-year-old country boy who had never been farther from home than Kansas City,” stated Kalberloh. “After hearing the stories of what (the Germans) had done to the Jews, we didn’t know what to expect.”

Toward the latter part of April 1945, General Patton and the 3rd Armor Division were approaching Nuremburg. In response, the German military marched thousands of prisoners—including Kalberloh—97 miles to Mooseberg.

However, the German plans of avoidance failed when—on April 29, 1945—Patton’s troops overran the camp and Kalberloh was finally liberated from his nightmarish experience of captivity.

“I remember seeing a tank followed by a Jeep and another tank roll into our (prison) camp,” Kalberloh said. “Patton was standing in the back of the jeep saluting.” Tearing up, the veteran remarked, “That was…and still is…the best day of my life.”

Kalberloh returned to the states in June 1945 and was discharged from the service the following September. In later years, he went on to work in the insurance industry and the Missouri Jaycees, and in 1992 retired from the Missouri Automobile Dealers Association.

Past commander of the Central Missouri Chapter of the American Ex-Prisoners of War Organization (an organization which officially dissolved on September 16, 2016) , Kalberloh notes how his military experience has affected his perception of something many have never gone without.

“The service taught me many things—such as discipline, but more importantly how valuable life is and that you had better take care of it,” Kalberloh remarked.

“It’s definitely more difficult for others to appreciate the freedoms they have when its never been taken from them…and I’ll never take that for granted.”