Elwyn Scheperle has many heartfelt memories of growing up in the Millbrook community south of Lohman, Mo., many of which involved listening to members of his family engaged in conversations in German. Though he picked up bits and pieces of the foreign dialect along the way, Scheperle admits he never thought it would ever be of any conceivable benefit … especially during a time of war.

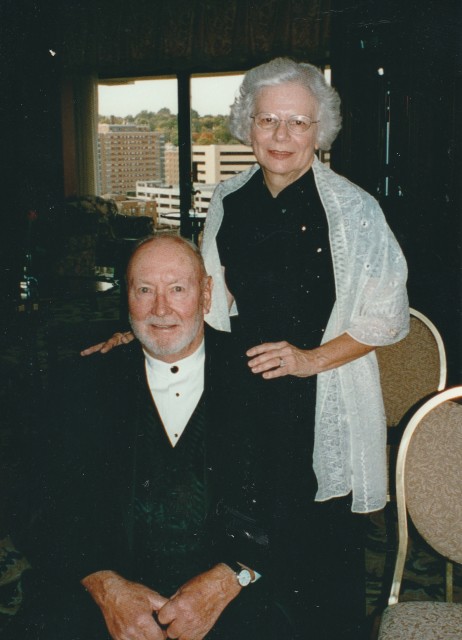

With World War II in full swing, the young farmhand received his draft notice in late 1944, thus sending the 20-year-old Scheperle on a journey that would find him directly communicating with people from a country his ancestors once called home.

“They sent me to Camp Roberts, California, for training,” recalls Scheperle. “It’s been so long, but I do remember that it was not much more than a desert with a few hills around it.”

In the weeks following the completion of his basic training, the young recruit went on to become a “cannoneer,” learning to operate the 105mm M2A1 howitzer, which was followed by additional instruction as an automotive mechanic.

“I had grown up around a blacksmith shop in Millbrook and had watched and learned a lot about working on things there,” Scheperle explained, while discussing his automotive training. “Back then, they expected you to be able to work on anything that needed repairs.”

In early April 1945, the newly trained soldier came home to Missouri for two weeks of leave before preparing to embark for overseas duty. Boarding a troopship in mid-April, Scheperle recalls departing New York and crossing the Atlantic in a convoy that included dozens of ships.

“Every direction that you looked, you saw a ship—to the front, back, right or left,” he said.

Arriving at a port in France nearly two weeks later, the men unloaded their ships and boarded trains that began dropping groups of soldiers off at different locations throughout France and Germany.

“I’m not sure where it was because things were so hectic at that time, but I arrived at a depot and they decided to put me as a replacement in an artillery unit.”

Days before the German surrender, Scheperle was assigned to Service Battery, 19th Field Artillery Battalion under the Fifth Infantry Division, and notes that replacement soldiers were a necessity since the division had experienced a significant number of combat casualties in the previous weeks from engagements including the Battle of the Bulge.

Though major combat offensives soon faded with the surrender of Germany on May 8th, 1945, the former soldier affirms that it certainly did not herald the end of his overseas activities since he soon became part of the occupational forces.

“The division had the hell kicked out of them, so we spent a lot of time fixing vehicles and equipment that had been damaged in battle—a lot of those old trucks were in pretty rugged shape,” he said. “We also pulled a lot of guard duty and even continued to do some artillery training.”

Moving between German villages, the division also gained the responsibility of checking homes and buildings that could be used to conceal German soldiers attempting to evade capture, a task that soon redirected Scheperle’s efforts.

“The guy that had been serving as translator (to speak to the residents when U.S. soldiers entered a German home) ended up in the hospital,” said Scheperle. “Word somehow got around that I knew how to speak some German and the officers decided that I should be the new interpreter,” he grinned.

The veteran admits the early days of his interpretive experience were challenging since the German he learned from listening to family in the Millbrook community was much different from that spoken by the German citizens they encountered during the occupation.

“I learned pretty quick,” Scheperle affirmed. “When we went in to check out a home, the people were usually really scared because they had been told all kinds of bad things about the Americans. But when we explained to them that we weren’t there to hurt them, they were very cooperative.”

As Scheperle explained, he was selected to be part a group of soldiers to be sent to the Pacific in support of the war raging in Japan; however, because of his duties as a translator, he was pulled from the group and remained in Germany until the surrender of Japanese forces.

In addition to his duties as a translator, Scheperle says, during the final weeks he spent in Germany he also served as the Jeep driver for his company commander.

In late August 1945, the soldier’s overseas service ended when he returned to the United States and was sent to Camp Campbell, to spend the remainder of his enlistment performing vehicle maintenance. He received his discharge the following July and returned to the Millbrook community.

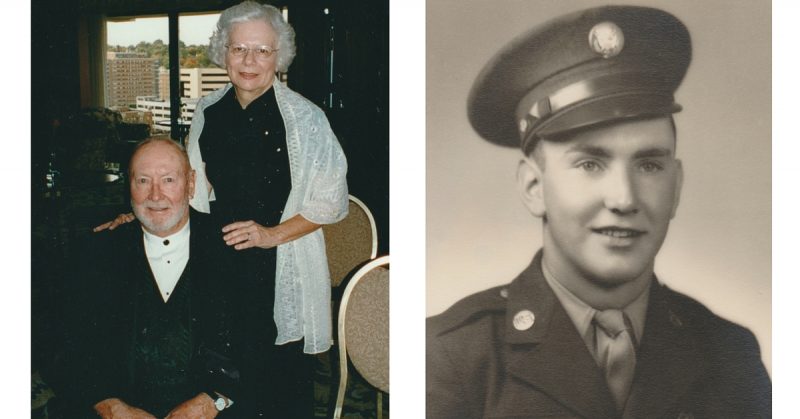

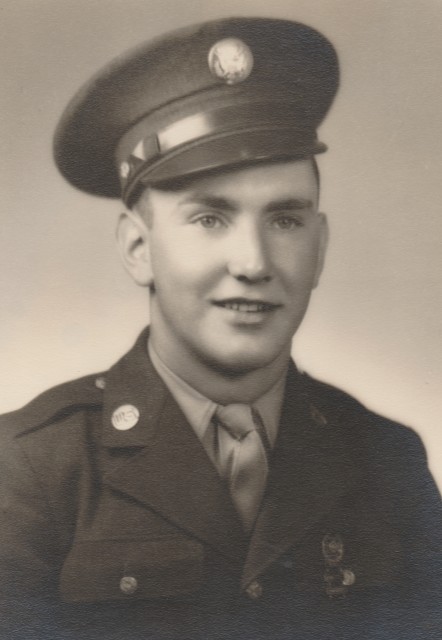

The veteran married Edna Ott in 1950 and the couple raised one daughter. Now retired, Scheperle spent many years self-employed as a heavy equipment operator.

With insightful reflection, Scheperle insists that although his arrival in Europe late in the war resulted in his missing some of the heaviest combat endured by the division, he cannot help but grin when contemplating the ironies he experienced while serving as a translator.

“If you really stop and think about it, it’s kind of peculiar,” Scheperle says. “Here I was, a young man coming from Millbrook with a German background, traveling to Germany during the war and then speaking German on behalf of the U.S. while I was there.”

With a grin, his wife adds, “If they had gone ahead and sent you to Japan, you would have really been in trouble.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.