War History Online presents this Guest Article from by Jerome Baldwin

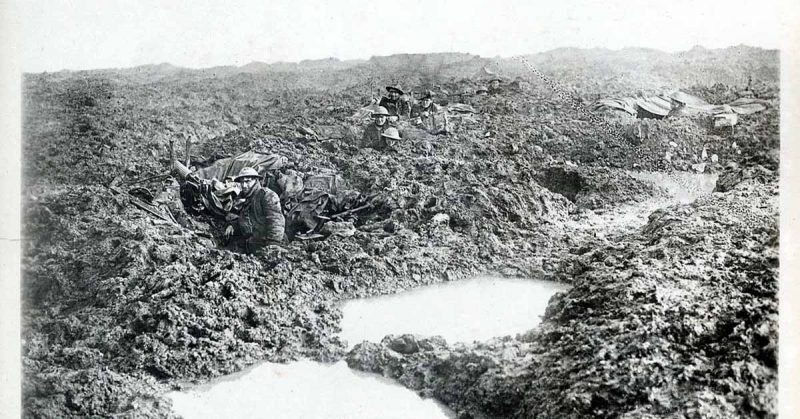

Ever since the Great War the legend of the wild deserters has endured. There are varying stories about them, but the core of the tale is this: a group of deserters from different and opposing armies – British, Australian, Canadian, Italian, French, German and Austrian – banded together and lived in underground caverns and dugouts in the midst of the shell-blasted desolation in certain sectors of the front. Emerging at night, they took rations, weapons, boots – anything they needed – off of the dead or dying. Like something out of a horror movie, some have said they also resorted to cannibalism, feeding off the plentiful supply of dead flesh between the lines.

The first stories of the tribe of deserters started, of course, from the men on the front line; with tales of hearing rifle shots and the voices of the wild deserters out in the shell-blasted wasteland, along with alleged sightings or encounters with the ghostly men. From the stories the legend grew.

One of the earliest published versions of the legend appeared in 1920, in a First World War memoir called “The Squadroon” by Ardern Arthur Beaman, who’d been a lieutenant colonel in the British cavalry on the Western Front. Beaman wrote that in the early spring of 1918, on the marshes of the Somme – where one of the costliest battles of the war had been fought in the summer and fall of 1916 – he witnessed about 30 German prisoners of war seemingly vanish into the ground. Continuing further on with his Troop, they came to the abandoned trenches and dugouts of the earlier battle line. “At one bound the war had rolled on from there to the Hindenburg Line.

The armies of France had swept over it and on, leaving it behind, and it was still as they’d left it,” wrote Beaman, referring to the German withdrawal eastward to shorten their line after the Somme battle.

As he and his men moved on, Beaman described seeing abandoned factories, many dead bodies, and plentiful supplies of food and ammunition. Soon they came to Fresnes, where they came upon a salvage company who told them they were the first people they’d seen since being there – and laughed at their mission of finding the group of escaped German prisoners they were after, as the system of abandoned trenches extended for miles. “They warned us, if we insisted on going further in, not to let any men go singly, but only in strong parties, as the Golgotha was peopled with wild men, British, French, Australian, German deserters, who lived there underground, like ghouls among the mouldering dead, and who came out at nights to plunder and to kill. In the night, an officer said, mingled with the snarling of carrion dogs, they often heard inhuman cries and rifle shots coming from that awful wilderness, as though the bestial denizens were fighting among themselves; and none of the salvage company ever ventured beyond the confines of their camp after the sunset. Once they had put out, as a trap, a basket containing food, tobacco, and a bottle of whiskey. But the following morning they found the basket untouched, and a note in the basket, “Nothing doing!”

In an autobiography entitled “Laughter in the Next Room”, Sir Osbert Sitwell, an Army captain and fifth baronet, described the wild deserters in this way: “For four long years…the sole internationalism – if it existed – had been that of deserters from all the warring nations, French, Italian, German, Austrian, Australian, English, Canadian. Outlawed, these men lived – at least, they lived – in caves and grottoes under certain parts of the front line.

Cowardly but desperate as the lazzaroni of the old Kingdom of Naples, or the bands of beggars and coney-catchers of Tudor times, recognizing no right, and no rules save of their own making, they would issue forth, it was said, from their secret lairs, after each of the interminable checkmate battles, to rob the dying of their few possessions – treasures such as boots or iron rations – and leave them dead.”

The legend has also appeared in novels such as “Behind the Lines” by William Frederick Morris, in which one British deserter meets up with another, who leads the two on to a dugout, one of the secret lairs, which was”…indescribably dirty and had a musty, earthy, garlicky smell, like the lair of a wild beast.” And more recently in “No Man’s Land” by Reginald Hill, where the legend of the deserters is central to the overall riveting story.

The legend has been dismissed as a myth – and likely is. There’s undoubtedly truth to the reasoning that it was borne out of the incredibly harrowing experience of front line duty in the trenches of the Great War. Under such conditions of madness, it stands to reason that such stories would rise up as sanity and a grasp of reality could both easily loosen. Perhaps an attempt to explain the unknown – such as the sporadic fire and cries sentries heard at night or what had happened to a patrol that never returned – also contributed to the legend.

But the fact is, as Sitwell wrote, we can never be sure. It was certainly widely believed by the troops then. And so was the story about what ultimately happened to the wild deserters of the Great War.

Deciding not to deal with them until the war’s end, the Allied Command did so when the shooting stopped and – according to the story – gassed the deserters after the Armistice.

Bibliography

Beaman, Ardern. 1920. “The Squadroon.” Web.

Cook, Tim. “Shock Troops.” 2016. Web.

Deutsch, James. September 4, 2014. “The Legend of what Actually Lived in “No Man’s Land” Between World War I’s Trenches.”

Swencer, Brent. “The Mysterious Wild Men of No Man’s Land.” September 7, 2015. Web.