In 1864, factions on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line grew tired of the destruction and carnage that had been waged for the last three years. President Abraham Lincoln worried that the stagnant predicament of the war would ruin his chances for re-election. His opponent, former Union General George B. McClellan, and Lincoln’s former commander of the Union Army, managed to garner the undying support of the nation’s Democrats with his promises of a negotiated peace with the Confederacy. McClellan assured his supporters that his election would be the solution to the country’s woes and an end to the bloodiest conflict in American history.

President Lincoln realized that in order to win re-election during a war and quell his detractors, he must demonstrate that to continue fighting the war would re-unite the Union. The president theorized that if he could secure the readmission of a southern state to convince the Confederacy the futility of any further resistance. The president targeted Louisiana to be that southern state and he saw an opportunity for the state to re-join the Union through “benevolent repatriation,” where, “re-entry of Louisiana…might inspire other Southern states to cease resistances.” Although New Orleans fell under the Union standard two years before in May 1862, the Confederates in Louisiana moved their capitol to Opelousas and then Shreveport, directing operations from there as military actions and the danger of capture warranted. Union execution of this plan and Lincoln’s hopes for a simple and short victory would be hard-fought as Confederate soldiers displayed a chivalric devotion to their cause.

In one of the last clashes of the war, the Battles of Mansfield and Pleasant Hill cured all doubts regarding soldiers still committed to the Rebel cause. After three years of Union domination and a notable lack of Confederate victories in Louisiana, these battles demonstrated the South’s commitment to ridding Louisiana of every vestige of Union influence, preserving some semblance of southern pride, and providing slim hope of an overall victory in the war. This would give the southern people a much-needed morale boost. Once thought to be the back roads of the Confederacy, the forces engaged at the Battles of Mansfield/Pleasant Hill formed the backbone of the Confederate corps. Her commanders proved more capable than most and realized that victory could be attained with a little patience and the exploitation of enemy weaknesses.

The Union plan for subduing the remainder of Louisiana’s forces and accomplishing Lincoln’s objectives had been sitting on the desk of General Henry W. Halleck, Lincoln’s Commander-in-Chief of the Armies, for almost a year before its significance would be recognized. Military leaders who actually reviewed the plan thought it “unnecessary.” General Ulysses S. Grant believed Mobile Bay should have priority over Shreveport due to its harboring of blockade runners. Admiral David Porter felt apprehensive moving his small force, “so far up an unfamiliar, twisting, small river dominated by high banks on both sides” when he spoke of the Red River in Louisiana. Subsequently, General Nathaniel P. Banks, commander of the Department of the Gulf, who, at first opposed such an operation, took into consideration that northern textile mills stood dormant because of a lack of cotton. Banks believed that in capturing shipments of cotton along the Red River he could make those mills operational again and redeem himself after losing a substantial amount of his forces during the disastrous Valley Campaign against Confederate demigod, General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. By achieving some semblance of victory in Louisiana with the new plan, Gen. Banks might just earn favor with his superiors and assign him to more martial duties.

The Red River Campaign called for Gen. Banks to march along the river itself, capture Shreveport with the assistance of Admiral Porter watching his flanks with supporting gunboats, and use the area around the city as a marshaling point for operations in East Texas. Gen. Halleck, on the other hand, planned to strangle the Confederate supply lines emanating from French intermediaries in Mexico. The French did not hide their support for the Confederacy and pressed with the possibility of troops being supplied to the Confederacy by the French from the South, Gen. Banks waited for assurances from Gen. Halleck that French aid to the Rebels could be strangled from the South before Gen. Banks attempted his advance in the campaign. Consequently, an incident occurred regarding a breakdown in communications between Mexico and France. Banks informed Halleck that, “there is little probability of reinforcements being sent to Mexico from France.” With this perceived difficulty resolved, Halleck ordered Banks to begin provisioning for the operation in January 1864, and proceed with the campaign in all haste.

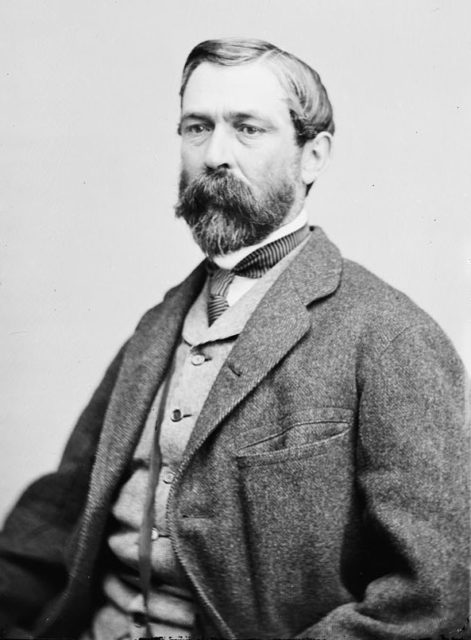

Major General Richard Taylor, son of former president Zachary Taylor and head the Confederate District of Western Louisiana, commanded Louisiana troops in the field and anticipated the enemy’s movements when, “Sherman (William Tecumseh) had visited New Orleans, I feared his cooperation with Banks from Vicksburg, but I had no means of estimating either the extent or time of such cooperation.” Reacting to this news, Gen. Taylor ordered a brigade under the command of Brigadier General Camille Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac, to proceed immediately to Alexandria. Gen. Taylor then received news that Fort DeRussy had surrendered, releasing Union troops for an attack on Shreveport. On March 15th, Gen. Taylor was notified that the Union gunboats made it to Alexandria on the Red River. Ever since the Union victories at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson, Louisiana, he expected a large Union army to meet him at some location along the Red River.

In an effort to harass Union troops on the march and leave nothing viable in the means of materiél for the enemy, under Gen. Taylor’s orders, Confederate troops confiscated everything from horses, to corn, to hay. Additionally, Taylor adopted a “scorched-earth” policy with his men burning tons of cotton despite the protests of merchants and planters from Opelousas to Shreveport. Taylor believed that Union forces were capable of laying waste to the entire eastern part of the state and any actions he could perform to serve the Confederate interests would certainly stall the Union army for enough time to gather the necessary forces to achieve victory over Banks and his men.

Having yet to encounter what Gen. Taylor and his troops had planned for them, Gen. Banks experienced difficulty with the U.S. Navy’s movements on the Red River. The crest was still not high enough to sustain the draft of most their gunboats or their transports. Admiral David Porter’s flotilla slowly crept up the Red River and still managed to fire their guns in their vulnerable ascent. Gen. Taylor learned that a Confederate transport, the Falls City, was standing by to be sunk near Grand Ecore, a small hamlet located just eight miles north of Natchitoches on the Red River. Because of the inland nature of the battles to come, Adm. Porter’s gunboats and transports would play a lesser role in the campaign than anticipated, but Taylor still took the threat seriously.

With the Confederates continuing their preparations for the Union armies’ arrival, on April 1st, writing from his headquarters near Shreveport, Gen. Taylor related, “As the enemy was moving up on the Natchitoches Road to Pleasant Hill in force I ordered Colonel Xavier Debray to push forward his batteries and trains with dispatch, which was done.” Gen. Taylor claimed to have “offered” battle to the Union army, but they refused so he left a cavalry division at Pleasant Hill and his infantry to Mansfield. In the early morning hours of April 2nd, General Thomas Green skirmished with some Union troops just outside Pleasant Hill. The bulk of the Union forces struggled to make their way up the Red River and by the time the Union army assembled for any major offensive, they numbered more than 35,000 men. Leading the way, General Albert Lee of the 1st Division cavalry unit, followed by three hundred wagons, three divisions of infantry from the 13th and 19th Corps, along with members of the Corps d’Afrique, black troops organized by the former military governor of the state, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler (the “Beast” of historical infamy), slogged their way through to Pleasant Hill and waited for the Confederates. With all his troops and supplies, Smith’s wagon train stretched some twenty miles long.

On April 3rd, Gen. Taylor supplemented his orders to Col. DeBray to move his army before daybreak, but DeBray did not make it from the town of Many to the Natchitoches Road until near sunset of that day. While en route, DeBray’s troops encountered a large enemy force, but protected his batteries and supply until an infantry unit covered his withdrawal so that the colonel could join Gen. Taylor at Mansfield. By April 5th, Gen. Taylor noted that he had not observed the Union army advancing on either Natchitoches or Mansfield roads, and reported through current dispatches from Col. DeBray that the Union army had, “fallen back on the road to DuPont’s Bridge, 18 miles below Pleasant Hill.”

With a major battle eminent, Gen. Taylor devised a plan to stall the Union forces even further. Although outnumbered and out-supplied, Taylor proved throughout his military career to be a commander who acted with decisiveness and sound military precedent; he also took risks and succeeded where other generals failed. However, Taylor suffered constant and persistent indecision on the part of General Kirby Smith, commanding the Army of the Trans-Mississippi, and made Gen. Taylor’s efforts to build a formidable force even that much more difficult. His available manpower stood at only 6,100 men and needed Smith’s complements to give the Confederates the slightest chance for victory. Gen. Smith planned to bring two cavalry divisions from Texas and two infantry divisions from Arkansas to bear. But until Smith’s forces arrived, Gen, Taylor waited impatiently for the action to commence. Finally, Taylor strongly urged Smith to expedite his actions so the Confederates could go on the offensive. Gen. Smith consistently delayed any action to the last possible moment and had a bad habit of inflating Union numbers. Gen. Taylor began to lose all patience with Kirby’s procrastination and strongly urged his subordinate to concentrate his efforts on defeating Banks, no matter the cost.

Calling on his previous military successes against long odds, Gen. Taylor devised a strategy where he would attack one of the Union’s larger columns. However, with Gen. Smith’s constant and persistent indecision, Taylor struggled to build a formidable force. His available manpower stood at only 6,100 men and needed Smith’s complements of Confederate troops. Gen. Smith planned to bring two cavalry divisions from Texas and two infantry divisions from Arkansas to bear. But until Smith’s forces arrived, Gen. Taylor found himself unable to act upon any strategy.

Smith’s lack of urgency caused Taylor turn to an alternative plan of action in preparation of battle. On April 6th, Taylor ordered Brigadier General James P. Major, Colonel William P. Hardeman, and Lt. Colonel Edward Waller, Jr.’s cavalry Brigades toward Mansfield. On the morning of April 7th, Gen. Taylor received word from Brig. Gen. Major from outside of Pleasant Hill that, “the enemy was advancing with a large force of all arms and was driving in our pickets.” Taylor then rode to Pleasant Hill on a reconnaissance mission to determine the enemy’s true strength there. On that evening, Taylor joined Major General Thomas Green where the cavalry commander informed his superior that Col. Dabray had marched from Many, Louisiana, to Pleasant Hill with the 36th Texas Cavalry Regiment. Taylor urged that Debray utilize his batteries expeditiously to keep Gen. Banks’ army from using the Shreveport-Natchitoches Stage road. Debray followed Taylor’s order implicitly. Taylor then implored Maj. Gen. Green to instruct cavalry units to harass the Yankee columns until he could gain sight of the main body of the Union army and fall back after a guerrilla strike against the Union main force.

With his army prepared for a land battle, Gen. Taylor then turned his attention toward the Union gunboats that were moving slowly up the Red River, still firing their guns during their hampered ascent. . Gen. Taylor’s concerns over his land forces took precedent over a potential naval threat. Taylor knew that Grand Ecore stood on a bluff overlooking the river; therefore, any Union breakthrough would be well-observed, swift and hold a well-organized tactical response.

If Taylor viewed the lack of naval participation as a Union advantage, Gen. Banks worried about the support the gunboats could provide the campaign. Banks reported to Edwin M. Stanton, the Union secretary of War, when he observed, “the river was perceptibly falling and the larger gunboats were unable to pass Grand Ecore…the condition of the river would have justified the suspension of the movement altogether at either point, except for the anticipation of such a change as to render it navigable.”

The change of which Banks hoped occurred on April 7, 1864, when Admiral Porter left his deep draft gunboats and proceeded to the Springfield Landing, some 100 miles above Grande Ecore. The shallow draft vessels included ironclads for fire support and approximately twenty troop transports carrying men, food, ammunition, and other provisions. Once they arrived at Springfield Landing, Gen. Banks ordered General T. Kilby Smith to reconnoiter the area toward Mansfield and secure the road leading to the town, if feasible. With this order, Banks lead his army into a well-organized and brilliantly executed Confederate trap.

On the evening of April 7th, Gen. Taylor issued orders to his commanders General Sterling Price and the 4,400 men under his command from Keachi, Louisiana, to Mansfield on a forced march of twenty miles beginning in the morning of the 8th. Taylor also ordered his provost marshals to prevent road jams and Confederate forces already commandeered houses and converted them into makeshift hospitals. The Rebels also utilized a wagon park as a dispersal area for provisions the army needed during the course of the battle.

The Confederate units situated themselves near the town of Mansfield along the Shreveport-Natchitoches road. General Alexandre Mouton, of the 2nd Infantry Division and Major General John J. Walker of the 1st Infantry Division formed lines to the north-northwest of town blocking the main road. Gen. Thomas Green’s situated his army to the east of Generals Mouton and Walker, almost parallel to the Shreveport-Natchitoches Road.

Gen. Banks appeared relentless in his strategy and refused to sacrifice his desire to incorporate the naval element into his campaign. The Union Army landed near Natchitoches and began their march toward Mansfield and Pleasant Hill. Elements of the Thirteenth Corps, under the command of Brigadier General Thomas E. G. Ranson, along with the Fourth Division, First Brigade, under the command of Colonel Frank Emerson, which included four infantry regiments; the Second Brigade, under the command of Colonel Joseph E. Vance; four infantry and two light artillery batteries; the First Cavalry Division under the command of Brigadier General Albert L. Lee; the Second Brigade of the Third Division under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Aaron M. Flory and Colonel William A Raynor, respectively; and the Fourth Brigade, First Cavalry Division, under the command of Colonel Nathan A. M. “Goldlace” Dudley.

As the armies faced each other, their battle flags barely waving in the dull, infrequent, April breeze, General Mouton broke the silence when he rode up and down the line, waving his hat and stopped in front of his old unit, the 18th Louisiana, shouting, “Louisiana drew first blood today!”

At dawn of April 8th, the Union units poised themselves where they could go no further without engaging the enemy. When Gen. Banks finally reached the battlefield, he noticed, “the skirmishers sharply engaged, the main body of the enemy posted on the crest of a hill in thick woods on both sides of a road leading over the hill on the road to Mansfield on our line of march.” Gen. Banks noted that the Confederate forces had grown substantially than previously reported. General Taylor realized that Gen. Banks’ positioned troops for an all-out assault to turn his right flank. The general, “brought Terrell’s regiment of cavalry to the right to reinforce Major, and Randall’s brigade, of Walker’s division, from the right to the left of the road to strengthen Mouton’s, causing the whole line to gain ground to the left to meet the attack.” Taylor continued to ride up and down the line to determine any weaknesses in the Confederate defenses looking for any breaches Gen. Banks could exploit.

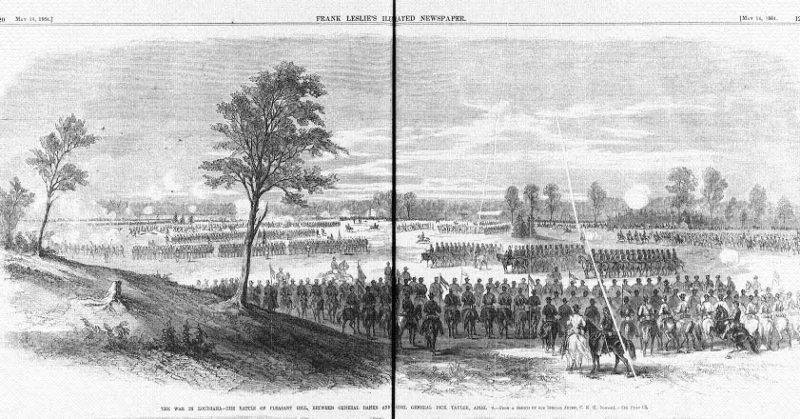

The battle began at approximately 10:00 am, and the Union line appeared to waver soon thereafter, but then the Third Division of the Thirteenth Corps arrived and formed a line straddling the Mansfield Road to the south. This line held the Confederates for shortly over an hour when the U.S. First Division commander, General William Franklin, sent a message to Brig. Gen. William H. Emory to immediately bring up the First Division of the Nineteenth Corps to the front and establish a reinforcement line to keep the Confederates at bay. The Confederates countered Gen. Franklin’s maneuvers and used their cavalry to full potential on April 8th. Gen. Mouton led a charge against the Union line on the right flank with full vigor and abandon where he, “crossed under a murderous fire of artillery and musketry.” During the charge, unfortunately, Gen. Mouton suffered several mortal wounds during the charge and later succumbed. Despite Mouton falling, several of his subordinates continued to press the attack. The timely assistance of Major’s Brigade, Bagby’s Brigade, and Vincent’s Brigade of the Louisiana Cavalry reinforced on their left by an infantry regiment managed to turn the Union’s right flank.

Gen. Taylor realized danger loomed for his right flank and as soon as the attack on the Union’s right flank commenced, Taylor ordered Maj. Gen. John G. Walker of the First Infantry Division to immediately move Brig. Gen. Thomas N. Waul’s First Brigade and Brig. Gen. William R. Scurry’s Third Brigade to his right flank. Because of this tactical maneuver, Union troops “formed new lines of battle on the wooded ridge, which are a feature of the country.” Gen. Waul and Gen. Scurry’s efforts turned the Yankee left flank and drove the Union forces back as far as four hundred yards and beyond a creek which served as the only water source for miles around.

Now in Confederate hands, guards posted near the creek received orders to shoot any enemy soldiers who approached. After several hours of exploiting breaks in the Union lines, the Yankees fully retreated, but only as far as Pleasant Hill. Mansfield proved a decisive Confederate victory and on the next day, the Rebels effort to hold the Union forces at bay demonstrated stern resilience, but Union forces pushed hard to avenge their defeat.

On April 9th, Union forces regrouped and withdrawn from the defeat at Mansfield, took up positions outside of Pleasant Hill, “joining the forces of General (A.J.) Smith, who had halted at Pleasant Hill.” At approximately 11:00 am, Confederate infantry sent scouts around the area they now occupied. After the reconnaissance, the Confederates formed on the left flank of the Union forces at Pleasant Hill, their movements slightly covered by the dense woods around the town. To cover a possible attack from his left flank, Gen. Banks situated an infantry regiment and portions of the Third Division under the command of Brigadier General Robert A. Cameron at that potential weak point. Small skirmishes and occasional artillery could be heard in the area throughout the day, but later in the afternoon, sometime around 5:00 pm, “the enemy abandoned all pretension of maneuvering and made a desperate attack on the brigades on the left of center.” Similar probes and eventual assaults occurred until approximately 9:00 pm on the 9th of April, where Gen. Banks noted, “The Rebels had concentrated their whole strength in futile efforts to break the line at different points.” Seeing no breaks in the Union line as the day before, Confederate troops ran into the woods chased by Union troops until darkness hampered their pursuit.

Gen Banks declared Pleasant Hill a Union victory, but did not produce the campaign success that Halleck, Banks, and President Lincoln had hoped. The Red River Campaign proved to be an unwise undertaking and ended not too long after the battle of Pleasant Hill. Banks squandered the lives of hundreds of men and depleted supplies that could have been spent in more meaningful campaigns. At first opposed to the operation, Banks saw an opportunity not for a whole Union victory, but actions that would benefit his political career. After the war, however, Banks’ presidential aspirations fizzled as a result of his own failures, but he did manage to get himself elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and the state house of Ohio. He died in September 1894.

General Richard Taylor brought victory in 1864, to a people who experienced nothing but defeat for a long time. Although the war continued for another year and the South lay in ruins after the surrender, the victory at Mansfield resonated in the minds of southerners as the complete southern victory with honor. Richard Taylor completed his memoirs after the war, Destruction and Reconstruction, and became active in Democratic politics. Taylor died in April 1879.

Mr. Gauthreaux is an author, historian, and educator from Louisiana. He is the author of 4 books, with his most recent being Echoes of Valor: Ordinary Men, Extraordinary Lives. The most recent work is the culmination of interviews with combat veterans from World War II through the Second Iraq War.