By Christopher Weeks

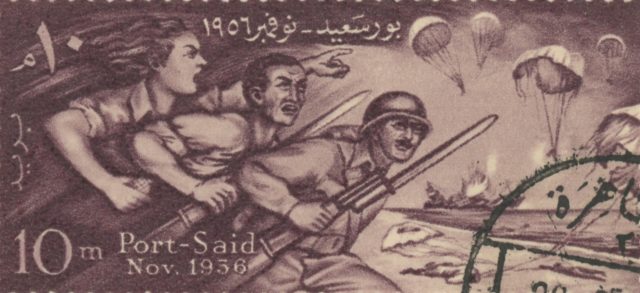

Sixty years ago, in the fall of 1956, Egypt faced the combined armed forces of three countries – Britain, France and Israel – on both sides of the Sinai Peninsula, in what is often called the Suez Crisis. Elite British and French paratroopers and marines invaded Port Said, at the northern end of the Suez Canal, which marked the western edge of the Sinai. Their Egyptian opponents were regular soldiers and draftees, policemen, militiamen and women, Muslim Brotherhood and Palestinian guerrillas, and civilian partisans. The British feared another Arnhem, the Egyptians would call it a Stalingrad, but in the end, Port Said was neither.

Britain, France and Israel all saw Egypt as a common enemy. Egypt had just seized control of the Suez Canal from Britain and France, threatening their access to Asian colonies. President Nasser was also helping Algeria in its war against French rule. Israel felt threatened by Egypt’s buildup of Soviet arms and its sponsoring of attacks by Palestinian guerrillas.

Israel invaded Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula on 29 October, and the British and French, acting as silent partners, then used this pretext to intervene, ostensibly to separate the warring parties but in reality to retake the Suez Canal. Their target was Port Said.

A gritty yet cosmopolitan port city, Port Said (and the smaller district of Port Fuad on the east bank of the Canal) had a long history with the British and French. Many of its 200,000 residents worked for foreign companies and the British military, and often resented being treated as second-class citizens in their own country.

Starting in 1950, guerrillas carried out sniping and bombing attacks on British troops along the Canal. At first the Muslim Brotherhood organized most of these groups, aided by sympathetic soldiers. Afraid of the growing power of religious radicals, the government tried to control these militias, renaming them the National Liberation Army and making them work with local police. They killed several dozen British soldiers and civilians and lost around 200 of their own before the British withdrew its soldiers but not its grip.

“We made a plan for continuous war if they invade us,” Nasser said, but he knew Port Said couldn’t hold out for very long. Instead, it would have to be made a symbol of Egyptian resistance and a headache for the British and French. No serious attempt was made to fortify or garrison the city until days before the invasion.

The Egyptian forces at Port Said were a very mixed bag. Two infantry battalions from the regular Army, three battalions of Army reservists, anti-aircraft and Navy coastal artillery units, three National Guard battalions, poorly-trained militiamen and women from the National Liberation Army, city police, and civilians. Some were children; others had fought the British for years.

Also among them was a young Palestinian lieutenant: Yasser Arafat. Called up for the Egyptian reserves, he previously fought with the Muslim Brotherhood guerrillas, now he was tasked with destroying vital infrastructure along the Canal to prevent them falling into British hands. Most of his platoon deserted, and with three remaining men he blew up an ammunition depot, unnecessarily it turned out, as British forces never threatened it.

Four SU-100 assault guns, arriving at the last minute, were their only heavy weapons. Arms depots and warehouses were emptied out; thousands of rifles, submachine guns and pistols were hastily distributed in the city. Egyptian intelligence agents and fishermen smuggling additional weapons into Port Said once fighting started.

Anglo-French airstrikes began on 1 November, wiping out the Egyptian Air Force and pounding targets around Port Said and across Egypt. The airborne assault began on 5 November.

Barrels and other obstacles blocked aircraft from landing at Gamil airfield, the British drop zone, but they became useful cover for the Paras. The National Guard defenders, battered from days of airstrikes, quickly fell back. The Paras took the airport and moved into the city, skirmishing with small groups of Egyptians and roving SU-100s, first at the city’s sewage plant then at a cemetery.

The French dropped into Port Fuad and after a fierce fight took the police barracks. 60 Egyptians died. The locals quickly learned that the French were ruthless fighters. Many were veterans of bitter guerrilla warfare in Algeria and Indochina. They shot dead one Egyptian simply for talking back. Resistance evaporated. The French convinced the defenders it was pointless to resist on the oncoming amphibious onslaught. By that evening, French paras and Egyptian police jointly patrolled the streets.

By contrast, the British soldiers seemed more restrained, and therefore easier targets. On top of that, Port Said was a larger, denser city than the suburban Port Fuad, making it a more favorable environment for guerrillas. Most attacks during the occupation were against the British, not the French.

The amphibious assault came on November 6. The French concluded their paras had done so well at Port Fuad that major follow-up landings were unnecessary. But the British had failed to secure the city and seize the harbor, and sent in two battalions of Royal Marine Commandos, backed by Centurion tanks and Buffalo amphibious carriers.

Most Egyptian soldiers in Port Said had now donned civilian clothing and operated in small groups. But they remained organized, with military intelligence General Abd al-Fattah Abu al-Fadl serving as the main link to Cairo from his base 50 miles south in Ismailia, and intelligence officer Kamal Rifa’at and police Major Mustafa Kamal al-Sayyid coordinating operations inside the city. The resistance fighters were organized into eight groups with five additional groups joining them from outside the city. Loudspeaker vans drove around the city broadcasting orders and encouragement.

“The government had given us weapons,” veteran guerrilla Haj Yusuf remembered. “After some hours we became many, many, many [in number]…. A popular resistance rose from the people inside Port Said. They never let them [the British and French] breathe, not a day…. They were afraid and they couldn’t stay.”

The British took key buildings after a few hours as the Egyptians were outflanked, outnumbered, or simply fell back. One Egyptian machinegun nest was placed in the middle of a hospital, trapping helpless civilians in the crossfire. Other Egyptians lay low as the British advanced; five Commando officers were killed or wounded by a stay-behind guerrilla who hid inside a wardrobe in an apartment building.

Wisely, the Paras and Marines chose not to move into the densely packed slums of the city’s Arab Quarter, known to the British as Arab Town, seeing no point in becoming bogged down in a nightmare of urban fighting. Probably aware of this, the local police station in this district became the headquarters of the resistance fighters.

The British also took advantage of their superior firepower. When Marines ran into tough resistance at the Customs Warehouse, the Centurions moved in. At the Navy House, 130 Egyptian sailors put up the strongest fight of the day, and the commandos simply called in airstrikes. The Marines assaulted the police station in helicopters – the first combat air assault in history.

In Port Fuad, the French landed some AMX-13 light tanks and additional troops. They killed or captured several dozen police in one clash, and paras blocked an attempt by hundreds of Egyptians, backed with T-34/85 tanks and SU-100 self-propelled guns, to break out of neighboring Port Said.

By the end of that second day of combat, the Anglo-French forces had prevailed by the sheer weight of their numbers. A ceasefire came into effect that night, but tensions remained high and Egyptian snipers worked through the night.

The next day, Anglo-French civil affairs teams went to work, restoring water and electricity, clearing dead bodies, and bringing in aid to trapped civilians. British commandos confiscated enough small arms to load 57 trucks, and dumped the weapons into the sea.

With the fighting over, the British paras and commandos left, replaced by an infantry brigade to occupy Port Said. The occupation lasted 46 days. These days were “tedious, uncomfortable and only at times dangerous,” in the words of one British soldier.

Cooperation between the Egyptians and the occupation forces was sometimes tense but often friendly, as they worked to solve local problems of daily life. Many of the Egyptians had worked with the British for years of course, and quickly fell into familiar routines. Egyptian police distributing food to civilians quickly became overwhelmed, and near-riots would develop, requiring British troops to move into protect the same police they had been shooting at weeks before.

By late November, the first United Nations peacekeepers began arriving to replace the British and French. The Egyptians greeted them enthusiastically.

As the invaders withdrew, Egyptian celebrations grew and became more raucous. Fuelled by propaganda broadcasts, sniping and grenade attacks on British patrols and checkpoints resumed. A British officer was kidnapped and his body found a week later. He had suffocated in the cupboard in which he had been held and buried by his captors.

The British took the gloves off, launching punitive night raids backed with tanks on Egyptian guerrilla safehouses. As the last British and French ships pulled away from Port Said’s docks on December 23, Egyptian snipers started taking pot shots. The volume of fire grew, and a massive fusillade of poorly aimed, mostly celebratory, gunfire arose from Port Said, a crescendo sendoff from the Egyptian soldiers and guerrillas from the Martyr City.

The British estimated 650 Egyptians died in Port Said during the invasion and occupation, and 100 more in Port Fuad, a quarter of whom were civilians. By contrast, British and French deaths were a fraction of that number: 16 British and 10 French soldiers.

Nasser’s propaganda machine turned the story of Port Said’s resistance to the British and French into mythology. The city became known as “the Martyr City” or “Egypt’s Stalingrad.” Like all myths, the comparisons are far-fetched but grounded in some truth.

The war was an embarrassing fiasco for Britain, resulting in the downfall of the government. For Paris, the war’s lesson was that alliances were unreliable, prompting France to leave NATO.

December 23, the day the last Anglo-French soldiers withdrew, became Victory Day, one of the most important secular holidays during Nasser’s rule. A locally produced submachine gun named the Port Said became an iconic feature in photographs and art.

The battle quickly made its way into popular songs. “Three nations in arms, but none ever had a foot in Port Said,” sang the Um Kalthoum, the Arab world’s most popular singer. “The voice of peace, victorious, prevailed, and our blood, spilled on the ground, shall never be wiped from our land.”

Another song, “Patriotic Port Said,” came out soon after the war. “In patriotic Port Said, youth of the popular resistance defended with virtue and virility and fought the army of occupation.” These lines were sung during the upcoming wars with Israel in the 1960s and early 1970s. Even during Egypt’s 2011 “Arab Spring” revolution, it was sung as an enduring anthem of patriotism and resistance. The battle of Suez was a tactical defeat for Egypt, but like so many military defeats, it became a rallying cry and source of pride.

By Christopher Weeks

weekschris@yahoo.com

© 2016 by Christopher Weeks

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andre Beaufre, The Suez Expedition 1956 (translated by Richard Barry), Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1969

Meriam Belli, An Incurable Past: Nasser’s Egypt Then and Now, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2013

Douglas Clark, Suez Touchdown, Peter Davies, London, 1964

Egyptianchronicles.blogspot.com, Nov.-Dec. 2006 postings

Rory Fullick and Geoffrey Powell, Suez: The Double War, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1979

Thomas Kiernan, Yasir Arafat: The Man and the Myth, Abacus/Sphere Books, London, 1975

Kennett Love, Suez: The Twice-Fought War, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1969

Yahia al Shaer, “The Other Side of the Coin: The Story of the Egyptian Resistance, Suez 1956,” https://web.archive.org/web/ 20081009135032/http://www.britains smallwars.com/Yahia2/index1.htm

Owen L. Sirrs, A History of the Egyptian Intelligence Service, Routledge, London, 2010

Ted Swedenburg, “Egypt’s Music of Protest: From Sayyid Darwish to DJ Haha,” Middle East Report, No. 265, Winter 2012

Derek Varble, The Suez Crisis 1956, Osprey, Oxford, 2003

Christopher Weeks, “Egypt’s Canal Zone Guerrillas: The ‘Liberation Battalions’ and Auxiliary Police, 1951-1954,” www.militaryhistoryonline.com/ 20thcentury/articles/egyptcanalguerrillas.aspx, 19 February 2011