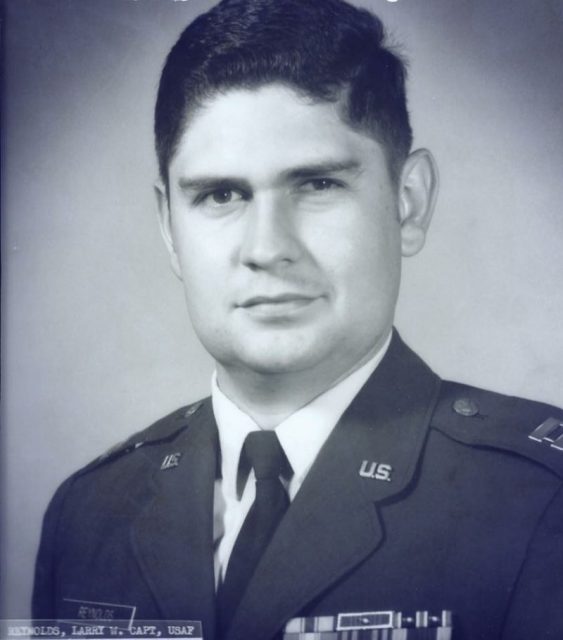

When graduating from Jamestown High School in Missouri in 1964, Larry Reynolds recognized an opportunity to continue his education through the University of Missouri-Columbia, participating in the school’s Air Force ROTC program. It was a decision that would later find him working around missiles with a nuclear yield of 1.2 megatons, which helped serve as a deterrent in a Cold War with the Soviet Union.

“I knew that I wanted an education and the ROTC program helped pay for that education,” Reynolds said. “While I was in college, I married my sweetheart, Sue, and I went on to finish my bachelor’s degree in accounting in January 1969,” he added.

Commissioned as a second lieutenant with the United States Air Force upon graduation, Reynolds was assigned to the former Kincheloe Air Force Base in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The young officer was soon greeted with the weight of responsibility in his first duty assignment.

As he explained, the base had crews assigned from the Strategic Air Command which used the airstrip for the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, a strategic bomber, and an aerial refueling aircraft known as the KC-135 Stratotanker.

“I was a 22-year-old second lieutenant with no active duty military experience when I got there,” he explained. “I reported on a Monday, inventoried and then signed for a million dollars’ worth of equipment.” He added, “The next day, the officer I was sent to replace left for another duty assignment.”

Assigned as a data processing officer for the 4609th Support Group, Reynolds had responsibility for 25 enlisted airmen and 35 different computer systems ranging from aircraft maintenance networks to those used by a civil engineering squadron to track base housing.

“I had to support the commissary, personnel systems, maintenance, inventory of nuclear weapons and supply systems…just to name a few,” he affirmed.

Accompanied by his wife on the tour, the first three years of his Air Force experience passed quickly because of his responsibilities on base. However, in 1972, now a first lieutenant, he received orders to Whiteman Air Force Base near Knob Noster, where he began a new mission that bequeathed him an entirely new level of accountability.

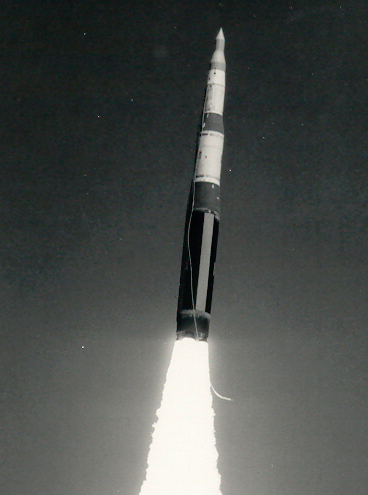

Selected for “missile duty,” he departed Whiteman for four months of training at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. While there, he learned about missile operations to include the equipment used, security protocols and the launch control facility.

This included simulated training scenarios that not only prepared the officers to launch missiles in a time of war, but also demonstrated how to respond in emergencies such as fires or losses of power.

“Everything is done by a very detailed checklist,” he said.

With his training complete, Reynolds returned to Whiteman and became a certified crewmember for the Minuteman II—an intercontinental ballistic missile with a 1.2 megaton nuclear warhead. During the height of the Cold War, Whiteman Air Force Base had oversight of the 150 Minuteman II missiles concealed in underground silos throughout western Missouri.

“I began to go on alerts in launch control center,” Reynolds said. “There were 15 launch control centers in Missouri and each center had operational control of 10 missile locations.”

The alerts, he explained, generally extended for two days. A commander and deputy commander worked in an underground “capsule” behind a 10-ton blast door at the launch control facility, monitoring missile activities during a 12-hour shift. A second crew came to relieve the first crew, who would then go to an upper level of the facility for 12 hours of rest, later returning for another 12-hour shift.

“In all, I pulled alert at most of the fifteen different launch control facilities,” he said. Discussing the characteristics of the weapons with which he worked, Reynolds added, “The missiles were said to have been so accurate, the warhead could be dropped onto a soccer field in Moscow.”

Achieving the rank of captain, Reynolds earned his MBA while stationed at Whiteman and remained in the missile program for three years. The officer was discharged in March 1975 after completing a little more than six years of service.

“I could have stayed in, but Vietnam was ending and I had a lot of friends who were pilots and held the rank of captain, but they were discharged because they didn’t make major,” he recalled. “Since I didn’t have my [pilot] wings, I figured it was just a matter of time before I was downsized, too.”

He and his wife returned to the Jamestown area and raised a son and daughter. In the years following his Air Force service, the veteran completed a career with the state of Missouri, worked 14 years for an insurance group and, though he has since retired, continues to operate his own accounting business.

Acknowledging that his time in the Air Force might not be considered as the front lines of combat, Reynolds maintains that he and his fellow missile crewmembers—in addition to support staff—provided a level of defense that helped deter an attack on the United States.

“We knew the level of destruction the missiles could deliver,” he said. “While we were in the first two days of our initial missile training, we were shown the destructive capabilities of nuclear armament through films of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II.

Read another story from us: Taos Warrant Officer Trains Next Generation

“After that training, they sent us back to our homes and told us to come back the next morning after deciding if we could do the job, which meant they needed airmen who would launch the missiles if ordered to do so.”

With momentary hesitation, he concluded, “You had to be able to resolve that issue with yourself. Fortunately, the missiles were available but never had to be used.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.