By Jeremy P. Amick

The Cold War, for many, was a period in our nation’s history filled with anxieties and fears as the United States and the Soviet Union faced off with scores of missiles at their disposal—initiatives that placed each country on a heightened alert and resulted in billions of dollars being poured into various strategic programs.

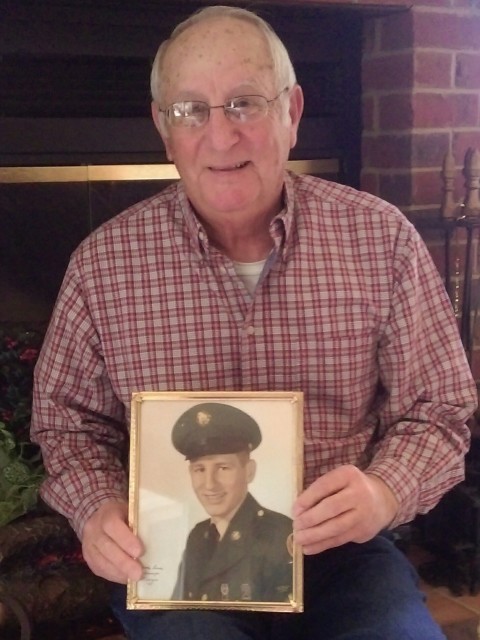

Chamois, Mo., area veteran George Kishmar affirms that although he came of age during this threat-filled period of our nation’s history, there was one missile program that seemed to resonate more with opportunity, not concern.

“The Army recruiter came down and gave a presentation to our senior class,” said Kishmar, 76, a 1957 graduate of Chamois High School. “When he told us about the different schooling options (in the Army), I really became interested in the Nike missile program,” he added.

According to a manual released April 6, 1970 by the Nuclear Training Directorate Field Command, the Nike-Ajax missiles “became operational in late 1953” and were the first generation of the Nike system, providing a weapon “whose range, altitude capabilities, and warhead lethality were far superior to the gun-type antiaircraft artillery.”

Enlisting in the Army in June 1957, after he was guaranteed electronics training, Kishmar was sent to Ft. Polk, La., for basic training. He then traveled to Ft. Bliss, Texas, for a 42-week electronics course that provided him the instruction and background necessary to serve as a maintenance person for the Nike-Ajax missile systems.

“We started out learning about basic electronics,” said Kishmar, while describing his initial time at Ft. Bliss. “Back then, most of the equipment that we used still had the old vacuum tubes. We learned to troubleshoot problems with the Nike system, such as broken wires or blown fuses.”

In describing the missile system, Kishmar noted that Nike “was a fairly new concept in electronics warfare—a surface-to-air missile designed to shoot down enemy aircraft.” He added, “It was guided through target tracking radar and would explode near the target and send shrapnel through it, like a shotgun shell going off.”

When his primary missile training was completed, the young soldier remained at Ft. Bliss for an additional 12 weeks of training on the newer Nike-Hercules missiles, which superseded the Ajax and had a surface-to-surface capability.

During the mid-1950s and early 1960s, nearly 250 Nike missile sites were constructed throughout the United States to serve as protection against the threat posed by long-range Soviet bombers, and were situated in areas that would allow for defense of key strategic sites. As such, Kishmar believed that once his training was completed, he would be assigned to one of these locations.

“Instead,” he said, “once I completed my training, I stayed on as an instructor at Ft. Bliss for the remainder of my enlistment.”

For the next two years, the soldier helped provide classroom training for new recruits that immersed them in all aspects of maintenance and operation of the missile systems—each system, which, he noted, consisted of three radars, a computer, launcher and missiles.

“Following the classroom training, each of the four batteries in our battalion would be issued a complete (Nike missile) system to set up, operate and maintain,” said Kishmar. “During the final phase of the training, we would move the equipment to (nearby) McGregor Missile Range and let each battery fire three missiles at radio controlled aerial targets.” (The targets, he explained, were similar to propeller-driven model airplanes.)

Once the training for the aspiring missile personnel was finished, they and their equipment were sent to one of the many Nike missile sites located throughout the United States.

While working as a trainer at Ft. Bliss, Kishmar recalls many humorous experiences that occurred, some of which were connected to their proximity to an Air Force base.

“Biggs Air Force Base bordered Ft. Bliss to the north, and at that time they were a Strategic Air Command and had B-36s, B-47s and B-52s stationed there,” he said. “The south runway took them directly over our barracks during take-offs and the noise was deafening … especially the B-52s.”

He added, “If you happened to be lying in your bunk when they took off, it felt like you were going to be crushed into your mattress.” With a grin, he concluded, “The local joke was (the soldiers) arguing about who would be assigned to clean the tire marks off the roof of our barracks the next morning.”

Kishmar completed his enlistment and was honorably discharged on June 6, 1960, enrolling at the University of Missouri a few months later. The following year, he married his fiancée, Mary Lou Stieferman and went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1965.

The Army veteran went to work for the Boeing Corporation in Seattle, Washington, remaining with the company until his retirement in 1995 after 29 years of employment. Two years later, Kishmar and his wife moved back to the Chamois area.

In addition to the experiences of working within a unique missile program during the heated period known as the Cold War, Kishmar affirms there were many valuable, less threatening lessons from his time spent in the Army.

“I had grown up in the rather isolated environment of a small town,” he said, “and suddenly I was pushed into an environment of big cities from all kinds of backgrounds—it was a real eye-opener!” he exclaimed.

“But the real take away from my time in the service was all of the electronics training I received in the Army because it really gave me a head start in college. And to be honest with you,” he concluded, “I’d do it all again in a heartbeat since it really is an excellent way for young men and women to develop a skill and learn to work with others.”