War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Distinction is a term that, when used to describe the men and women who served in the First World War, applies to a small list of individuals and includes such leaders as General John J. Pershing, who went on to serve as commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe.

Under Pershing’s command were millions of anonymous soldiers from throughout the United States who did not collect accolades for their battlefield performance, but did their duty and returned home to preserve their experiences by sharing stories of their service with their families.

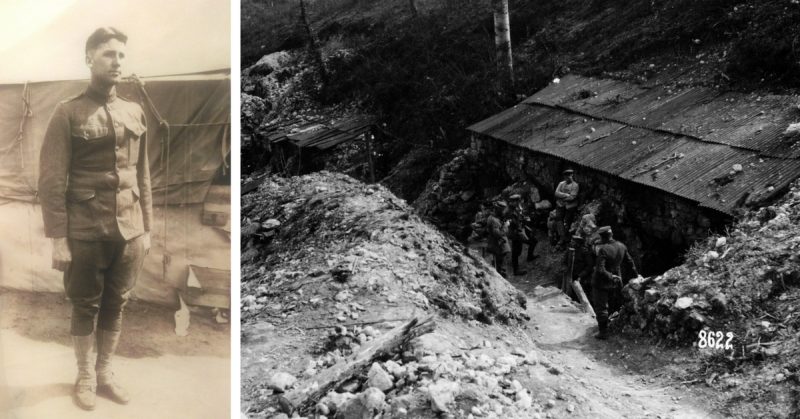

Born in Kansas City, Kansas, on May 9, 1896, Clarence Hubbard became one such veteran who chose to pass down his WWI experiences. He left his Kansas home at a young age to work for a farm family in the Brazito area but was thrust into combat shortly after the United States declared war against Germany on April 6 1917.

“He made the decision to go ahead and enlist in the Army; he wasn’t drafted,” said Steve Jannings, the veteran’s nephew.

According to Hubbard’s WWI service card, he enlisted in Company L, 2nd Missouri Infantry Regiment of the Missouri National Guard in Jefferson City on May 15, 1917. Less than three months later, the 2nd Missouri was federalized and the various companies of the regiment assembled at Camp Clark in Nevada, Missouri.

Hubbard and the soldiers of the regiment soon learned their “federalization” would change their National Guard company’s designation to Company C, 130th Machine Gun Battalion under the 35th Infantry Division. The battalion then traveled to Camp Doniphan, Oklahoma, spending nearly six months in training before departing for France in May 1918.

“(Hubbard) never really talked much about the battles and things that they went through overseas,” said Jannings, “but he did share with me many of events he found interesting and humorous.”

The book “History of the Missouri National Guard” notes that the 130th Machine Gun Battalion arrived in England on May 15, 1918 and was sent to Le Havre, France days later. They were eventually sent to a French village where, the book notes, “they received a full complement of French Hotchkiss machine guns … and training with them (was) instituted.”

Jannings remarked, “A lot of the stuff they did back then was done with mules. He a talked about it taking two men to set up the machine guns, and ammunition for them was then brought in by mules.” He added, “One man carried a tripod and the other carried the machine gun and each one weighed 85 pounds, he told me.”

The 130th participated in some of the most gruesome engagements of the war, the most notable of which was the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in late September 1918. This battle took the lives of more than 26,000 American soldiers within six weeks’ time including fellow Company C member, Roscoe Enloe, for whom the American Legion Post in Jefferson City is named.

As a machine gunner, Hubbard often had a front row seat to many of the bloody onslaughts and spent a fair amount of time living in the squalor of trenches; however, Jannings explained, it was the humorous situations he truly found joy in sharing.

“The French made cognac and they hauled it in big containers on flat rail cars,” Jannings said, recalling past conversations he had with Hubbard. “One day, they got wind a train was going to come through hauling cognac so the boys got together, sized up the situation, and when the train arrived, they poked a hole in a barrel and filled their canteens or anything else they could find to hold liquid.”

With a chuckle, Jannings added, “Then they had one heck of a big party.”

When the war ended with the armistice on November 11, 1918, the 130th Machine Gun Battalion incurred the battle loss of 26 enlisted soldiers, 11 officers and 176 men wounded. The battalion remained in France for several months and returned to the United States in April 1919. Hubbard received his honorable discharge on May 7, 1919.

The month following his discharge, Hubbard married Cecelia Ritter of Lohman and the couple began working the farm that for years had been in his wife’s family. However, Jannings said, a few years later Hubbard chose to increase his income through a questionable opportunity.

“During Prohibition, he purchased a 1929 Chevrolet and would pick up moonshine made by a guy in Lohman and another guy in Russellville and deliver it to a speak-easy in Jefferson City. He was never caught, but the guys making the moonshine were and spent some time in the penitentiary.”

In the years after the war, Hubbard gained a level of local attention for an immense collection of arrowheads and Native American artifacts found on his farm, which he chose to display in the front room of his house. For years, Jannings explained, people would come from all around to view his collection.

Hubbard passed away on January 21, 1971 and was laid to rest in the cemetery of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Lohman. His service in the war may have appeared trifling within an army of more than four million men, but Jannings is content knowing his uncle’s story has been preserved through retellings.

“I’m not sure that we have a lot of men like that anymore—he was tough and of rough character but he was also very kind, a hard worker and a good farmer. Many people don’t realize the atrocities that happened in the war but he talked about the Argonne forest and said that the firepower was so intense that after they left, there wasn’t even a bush left standing.”

He added, “None of the WWI guys are with us anymore and their stories are gone. When (Hubbard) spoke about some of the things he remembered from over there, it helped me to know the man that he was and what all he experienced.”