War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

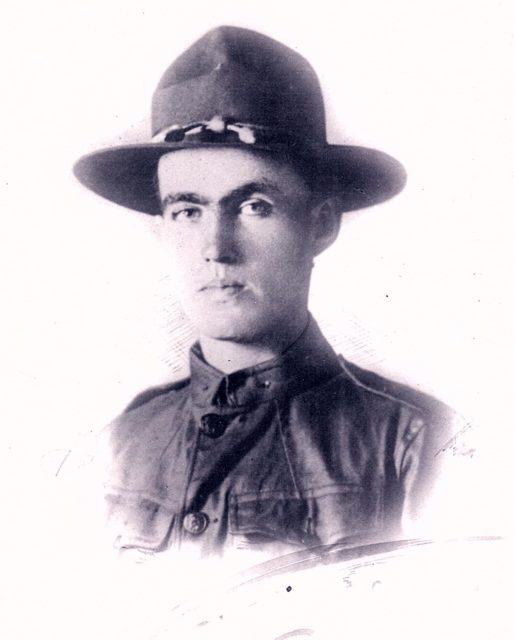

The name Layton Longan has been all but erased from the memory of the Mid-Missouri community since the young man, who was killed in 1918 while fighting in World War I, has little more than a small grave marker to perpetuate his legacy. Yet a historical society located in a small French village seeks to memorialize Longan and several American servicemembers who made the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of their freedoms.

In an email to the state department of the American Legion, Hubert Martin, president of a historical society in Alsace, France, wrote that he is seeking information on the life of Longan so that he can be honored during memorial events in September 1918, along with four dozen other American soldiers who fell in battle in the mountains of Alsace during WWI.

Born on a farm north of California near Kliever, Mo., on October 23, 1894, Longan was the youngest of three children. In 1916, his father passed away and the following year the United States entered into the First World War. As evidenced by his registration card, the 22-year-old fell into the age group required to register for the military draft on June 5, 1917.

At the time of his registration, Longan had worked six months for a farmer in Jamestown although he resided in the community of Tipton; however, on July 2, 1917, he traveled to Sedalia and “enlisted in the Missouri National Guard … and with this organization was inducted into Federal Service …” reported the California Democrat on June 23, 1921.

Assigned to Company D, Sixth Missouri Infantry Regiment, the book “History of the Missouri National Guard,” explains that both the Third and Sixth Missouri Infantry Regiments were consolidated to form the 140th Infantry Regiment under the 35th Division during WWI, and moved to “Camp Doniphan, a horseshoe-shaped site on the hard sands of Oklahoma, within the Fort Sill Reservation …”

Longan and his fellow soldiers had many hardships cast upon them by Mother Nature prior to their deployment overseas, spending the first part of their service in Oklahoma battling dust, which was followed by “particles of snow, mingled with the blowing sand (that) cut the skin like a knife.”

The cycle of adversity continued “with an epidemic of spinal meningitis, forerunner of the nation-wide epidemic of Spanish influenza of the next year,” bringing yet additional misery to the soldiers who were in the final stages of preparing for the uncertainties of trench warfare.

In April of 1918, the men of the regiment boarded trains, eventually arriving in Hoboken, N.J., “where we quietly marched up the gangway into the (troop) ships that were to be our home for the next two weeks,”wrote Evan Alexander Edwards, regimental chaplain and historian, in his book “From Doniphan to Verdun: The Official History of the 140th Infantry Regiment.”

Edwards goes on to explain that the soldiers of the Missouri regiment were soon in France and embued with the desire to join the fray after witnessing wounded soldiers being transported on a Red Cross hospital train.

“The sight sobered us, and increased our desire to get to the front,” he revealed.

The regiment, including Longan, received their first “look at the Germans through the sites of (their) rifles” when they moved to the trenches in the latter part of July 1918. They soon received their bapistm of fire under German artillery barrages and attempted raids on their trenches, the latter of which were repelled with their American Enfield rifles.

For the next several days, artillery bombardments endured, eventually taking the life of young Private Longan on August 14, 1918. As the regimental chaplain explained, Longan—and several of his fellow soldiers killed in the attacks “were buried reverently, their bodies laid to rest with loving care” in a cemetery near the small village of Linthal, France.

In a letter to Longan’s mother dated August 15, 1918, Lt. Albert G. Gardner—a Chicago native and commander of Company D, 140th Infantry Regiment—wrote, “We, the young manhood of our great free nation, are fighting for the liberty of our country and the world.” He added, “Your son lost his life in the face of the enemy. His duty to his country, to his home, and to his God is nobly done.”

The early days of trench warfare by the regiment became the end of watch for many, but the survivors went on to fight in several major engagements of the war, remaining in Europe through the spring of 1919. Longan, however, did not return home until two years later when, as reported by the California Democrat on June 23, 1921, his remains were returned to the U.S. and interred in the New Salem Cemetery north of California.

Private Layton Longan—a young farmboy from Moniteau County who answered the nation’s call to colors during the “war to end all wars”—may not be memorialized in any magnificent marble or bronze monuments, yet a small historical society in France is striving to ensure that his sacrifice, and that of his contemporaries, endure in the memory of the French people.

“I’m looking for information about each soldier (who died in action near Linthal),” wrote Hubert Martin, president of the historical society in Alsace, France, noting that Longan’s story will be used during WWI commemoration ceremonies in Linthal in September 1918.

He added, “I send you my best greetings from France and thank you so much for helping us not to forget all these soldiers who lost their life for our liberty.”