By Jeremy P. Amick

In the book “The Missile Next Door: The Minuteman in the American Heartland,” author Gretchen Heefner wrote, “Between 1961 and 1967 the U.S. Air Force buried 1,000 Minuteman missiles across tens of thousands of square miles of the Great Plains.” She further noted that for three decades, these nuclear warheads remained “on constant alert, capable of delivering their payload … to target in less than 30 minutes.”

In later years, the program was modernized to the Minuteman II—intercontinental missiles possessing even great precision. For more than three decades, parts of western Missouri served as home for 165 Minuteman II sites, requiring scores of Air Force personnel to operate and maintain.

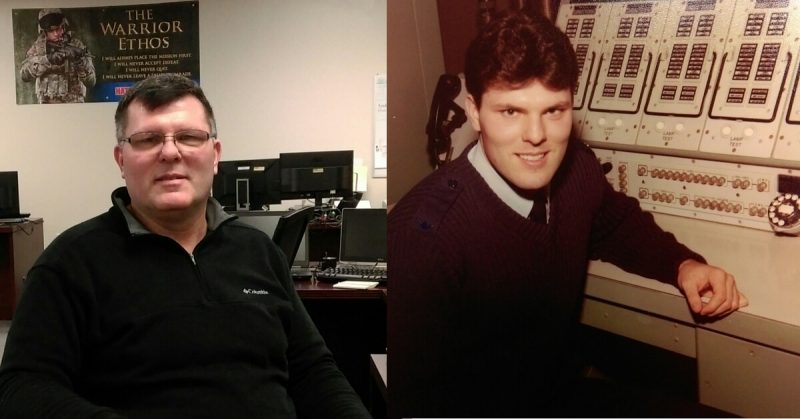

As local veteran Craig Collins explained, his experience in working within such a program was one characterized more by coincidence than design.

Graduating in 1980 from high school in Arlington Heights, Ill., Collins, like so many his age, decided to “give college a chance,” however, two years later, he tweaked his educational objectives and enlisted in the Air Force.

“One reason I decided (to enlist),” Collins said, “was that I thought it might be my best chance to acquire skills that would be applicable to civilian life … like working with computers and satellites, both of which were getting pretty big at that time.”

The young recruit traveled to Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, for his basic training in June 1982. During the waning days of his training, he discovered that because he had selected an “electronics” specialty upon his enlistment, the Air Force decided his services would best be best suited for their missile program.

“I was sent to Chanute Air Force Base (Illinois) for the missile systems analyst specialist course,” he recalled. “At first, I was very excited because I thought I would be working with the latest technologies.”

Yet the young airman’s excitement was soon tempered when he learned that many of the missile components that he worked with were often more than 20 years old.

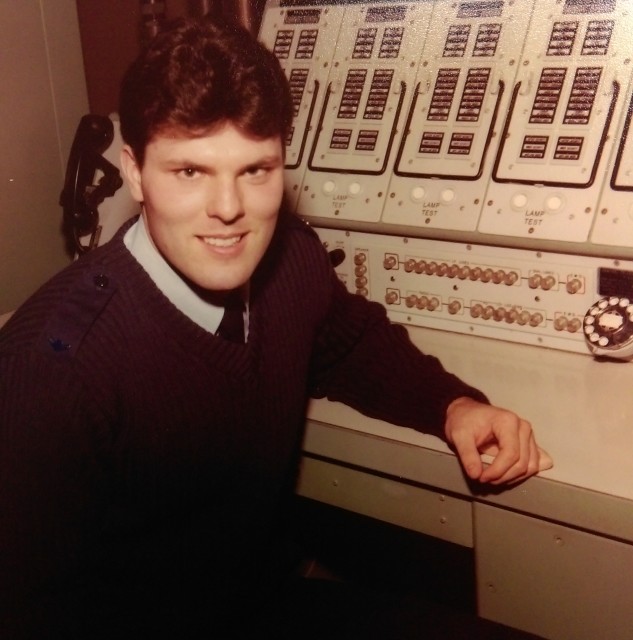

While at Chanute, Collins noted, he and his fellow trainees spent the next 33 weeks learning everything from basic electronics to maintaining and repairing launch control panels, in addition to operating the equipment used to re-target the Minuteman II missiles.

Graduating from the missile training in early 1983, Collins received assignment to the 351st Organizational Missile Maintenance Squadron located on Whiteman AFB near Knob Noster, Mo.

“We were on electrical/mechanical teams,” said Collins, “and essentially worked on all of the support equipment inside the (missile) silos. During my time in the Air Force, I think I was in just about every silo and launch control center in the state.”

According to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources website—who, along with the EPA and the Air Force continues to monitor for contamination the former missile sites within the state —Missouri served as host for 150 missile silos (which were buried at a depth of 80 feet) and 15 launch control facilities.

“The technology we were working with was so old that if we needed to re-target a missile, we could not do that from one of the launch control facilities,” Collins said. “We had to go out to the missile silo and do it on site, because even back at that time, the missiles had been in the ground for about 20 years.”

As described by the National Park Service on their website, the Minuteman II was an enhanced Minuteman I design offering an “improved range, greater payload, more flexible targeting and greater accuracy.” When combined with a “kill capacity” that was eight times as great as its immediate predecessor, the newer design helped thrust “the world into a new era of weapons for mass destruction.”

This destructive capability became a realization that was certainly not overlooked by the young airman from Illinois.

“The first time I went onto a Minuteman site, it had a pretty big impact on me,” said Collins. “There was a certain dichotomy—right in the middle of a field of some farmer who was working to feed people was this major destructive force that carried the potential of destroying an entire city.”

Collins remained on Whiteman until his discharge in May 1986. In later years, he went on to serve a stint in the U.S. Army and eventually retired from the Missouri National Guard in 2012. The veteran is now employed as a contractor supporting the Missouri Guard’s Recruit Sustainment Program.

Many years have passed since he last worked with Minuteman II missiles and evidence of the silos that once held them have all but disappeared from the landscape, but Collins insists that he experienced divergent emotions when he first learned of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty and the removal of the missiles.

“When the missiles were removed (from Missouri and other Midwestern states), I really viewed it with mixed emotions,” he said. “I and others had spent so much time making sure these missiles would be able to launch at a moment’s notice … if necessary.”

He added, “But then I realized that we were destroying these missiles that never had to be used—that no one had been hurt and that they had done their job by serving as a deterrent. I was glad that they were no longer needed.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.