War History Online presents this Guest Article from Charley Valera

“NUTS,” an official military response to a German commander. The response was to a German letter threatening to annihilate over 100,000 US troops in what was to be known as The Battle of the Bulge.

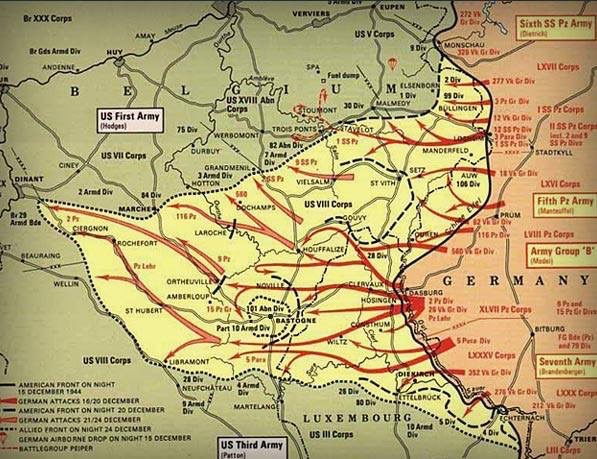

Seventy-four years ago on December 16, 1944 Adolf Hitler ordered what eventually would be the last major offensive of the Third Reich. The plan according to some of my interviews with WWII veterans that were there, looked like it might work.

The plan was to split, surround and capture—or kill the—US troops. They would use a surprise all-offensive attack known as a blitzkrieg. The thick Ardennes forest in Luxembourg and Belgium was the perfect location for the ambush. It was a brutally cold winter, roads were either non-existent or impassable. The Allies had miscalculated the German’s and had two battered and inexperienced divisions soon to be surrounded. Over a quarter-million German troops were moved into place as all hell broke loose as they advanced into Bastogne.

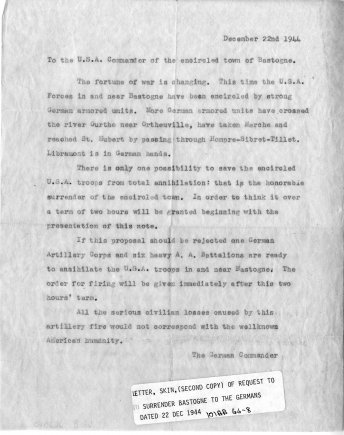

After a week of battle, on December 22, at 11:30 am, four German soldiers waving white flags approached the American lines. Major Wagner from the 47th German Panzer Corps requested to see the US commanding officer, he had a written message to deliver. The German soldiers were blindfolded and eventually brought to Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe. The message was this surrender letter:

“December 22nd, 1944

To the U.S.A. Commander of the encircled town of Bastogne.

The fortune of war is changing. This time the U.S.A.

forces in and near Bastogne have been encircled by strong

German armored units. More German armored units have crossed

the river Ourthe near Ortheuville, have taken Marche and

reached St. Hubert by passing through Hompre-Sibret-Tillet.

Libramont is in German hands.

There is only one possibility to save the encircled

U.S.A troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable

surrender of the encircled town. In order to think it over

a term of two hours will be granted beginning with the

presentation of this note.

If this proposal should be rejected one German

Artillery Corps and six heavy A. A. Battalions are ready

to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne. The

order for firing will be given immediately after this two

hours’ term.

All the serious civilian losses caused by this

artillery fire would not correspond with the well known

American humanity.

The German Commander.”

US Lt. Col. Harry Kinnard the Division Operations Officer asked, “They want to surrender?” to which Acting Chief of Staff Lt. Col. Ned Moore responded, “No sir, they want us to surrender.”

McAuliffe was furious. He responded,”Us surrender, aw nuts!”

As the clock of destiny was ticking away, the German officers were still waiting the response from McAuliffe. Meanwhile, in front of his staff, McAulliffe said,” Well, I don’t know what to tell them.” Kinnard responded,

“What you said initially would be hard to beat.” An unclear McAulliffe asked, “what do you mean?” to which Kinnard responded,”Sir, you said ‘nuts’.”

A perfect american response was quickly typed up.

“December 22, 1944

To the German Commander,

N U T S !

The American Commander”

https://youtu.be/bqOPeXLnfF8

McAuliffe requested Col. Bud Harper, the 327th Regimental Commander to review the initial surrender demand and come up with a response. However, Harper was then handed the typewritten response and asked if it was a proper reply. Of course, Harper laughed and was told to deliver the message personally.

Harper did indeed deliver the reply to the German officers that were planning to discuss the US surrender terms. When asked what the reply meant, “Is that negative or affirmative?” Harper replied, “The reply is decidedly not affirmative. If you continue this foolish attack, your losses will be tremendous.”

General George S Patton was informed about the dire situation and promised to have his troops to help McAulliffe in three days time. As impossible as that seemed, Patton delivered. “Nuts” turned out to be very motivating to the US troops.

The battle turned out to be the most ferocious and costly of WWII. As a result of incredible cold weather with ice, fog, snow and rain along with a lack of food, supplies and rest. The much-needed air support was also delayed. The fighting lasted non-stop for 35 days with the casualties combined from both sides of over 175,000, more than 5000 per day.

“My Father’s War” featured veteran George Pelletier’s story was featured in The Bulge Bugle magazine, the Official Publication of The Battle of the Bulge Association.

Pelletier recalled,”The [Heinies] spotted us coming around the hill and started picking us off. Shells were landing everywhere as close as 5 yards from me. I was dazed but prayed like mad. I then spotted a hole in the ground, which probably saved my life, as three men behind me were hit. We took a beating that day. We dug in that night under fire. At 4 the next morning we took off or jumped off into the attack once again minus anything to eat or drink and minus sleep. That day we advanced 5 miles into the woods, flanking our objective, while other companies came in on the other sides. Again we were shelled continuously, one of my buddies was killed, two more wounded, all in my platoon. Soon we ran out of ammunition, had no water or food.”

Another veteran from “My Father’s War,” Charlie Sanderson, was also fighting during the Battle of the Bulge. From a distant memory, Sanderson remembered another interesting story, detailing what the Ardennes Forest looked like.

“Did you ever see land when tornadoes come through? Did you ever see trees and branches, twisted and broken off? The whole friggin’ forest was like that. I drove down a road and there were horses hooked to cannons — German horse-drawn artillery. Our men came down through and strafed them. We just had to push them off the road so we could get through. Imagine that — using horse-drawn artillery in World War II. Everything the Germans had, they used. That was the Ardennes Forest.”

Sanderson was stunned to see the once-mighty Third Reich reduced to using horse-drawn artillery.

“They called them battles, but to me it was one long battle all the way through. When you can’t see it, you get scared. You don’t know where it’s coming from. Anyone who said they weren’t scared is a damn liar.”

Charley Valera

Visit his website “My Father’s War: Memories from Our Honored WWII Soldiers”