July 20

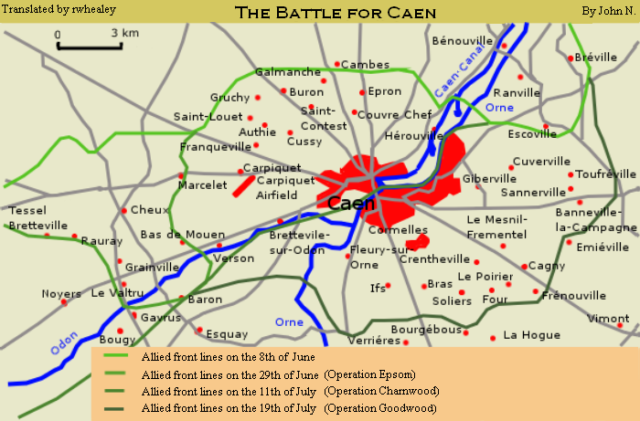

July 20th 1944 marked the third day of Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery’s massive armored thrust “Operation Goodwood” against the Germans in the Caen area. “Goodwood” was meant to break the deadlock that had gripped the fighting in Normandy ever since D-day. Supported by the Canadian II Corps and the British I Corps on its right and left flanks, respectively, General Sir Richard O’Connor’s VIII Armored Corps was pitted against the German LXXXVI Corps and the I SS Panzer Corps. The British and Canadians needed to oust the Germans out of southern Caen and from the commanding Bourguébus Ridge. Once this was done, the British armor could break into the open country beyond and strike for Falaise. Despite huge artillery and aerial bombardments, the two days of hard fighting had gained little ground. The German defense was deeper than anticipated and had only grudgingly given away.

The day began promisingly enough as Major General Sir Allan H.S. Adair’s Guards Armored Division thrust towards the southeast, taking Frénouville and Emieville. The villages, hotly contested earlier, were abandoned by the youths of Kurt “Panzer” Meyer’s 12th SS Hitlerjugend Panzer Division. The fighting picked up at Vimont, where the Guards were repulsed by the Hitlerjugend. In the British center, the 7th Armored Division finally secured the likewise abandoned Bourguébus village. But its 4th County of London Yeomandry Armored Regiment and a company of the 1st Battalion Rifle Brigade were prevented from advancing further up the gentle slope toward Verriéres by the fire of Waffen-SS panzers. The latter including the Tigers of Hauptsturmführer (Captain) Michael Wittmann’s 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion. Wittmann, one of the greatest tank aces of all time, had been promoted to battalion commander just over a week ago.28

Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army, had come up with the Goodwood idea. At the end of the first day of battle, Dempsey had felt so confident that he had even turned down an offer from Tactical Air Force for a bombing run of Bourguébus ridge because he thought it unnecessary! Now, two days later, Dempsey decided that his armored regiments were too battered to continue and ordered the tanks to pull back. Eighth Corps would hold its current positions with infantry. It was now time for the Canadians to show their mettle and make a try for Verriéres. On the western flank of the British Armor, General Guy Simmonds’ Canadian 1st Corps had already seized the Caen suburbs and factories from the 272nd Infantry Division and from elements of the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division. The gains, however, had come at a cost of 200 Canadian casualties.

Around 1500hrs, supported by Canadian and British artillery fire and Hawker Typhoons, the Canadian 6th Infantry Brigade met the Waffen SS and a newly arrived Kampfgruppe (Battlegroup) of the 2nd (Austrian) Panzer Division in a climatic final to the battle. In a reverse of earlier British armored attacks, which lacked infantry support, the Canadian infantry attacked with precious little tank support. The Canadians nevertheless began with a promising start. “The weather was hot and the roads were dusty,” recalled anti-tank gunner Gordon Amos, “We were green but we soon ripened up.” Supported by rocket firing Hawker Typhoons, the Camerons of Canada seized St. Andre-sur-Orne from the 272nd Infantry Division. Shortly thereafter the Germans plastered the village with artillery and mortar fire. The South Saskatchewan Regiment struck for the Beauvoir and Torteval farms. German sniper fire hit the Canadians from wheat shocks. The Canadians replied with phosphorus grenades. “When the snipers see the odd guy come screaming out of a grain stook, his uniform covered with burning phosphorus, they start popping up all over the place with their hands up” related Captain Britton Smith.

After rainfall drove off the Typhoons, the Mark IV panzers of the 5th and 6th companies of the Leibstandarte’s 2nd SS Panzer Battalion and a StuG company emerged from hiding. Supported by SS grenadiers, the German armor viciously counter assaulted. Lethal fire from the dreaded MG-42s, nicknamed “Hitler’s scythe and buzz saw,” cut down scores of Canadian infantrymen. Panzer shells burst up the few supporting Canadian tanks. The Canadians in the center broke and ran through the cornfields. Panthers rampaged through the wheat fields with impunity, flushing out their hidden prey. Two companies of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal were all but annihilated. In its first real action, the South Saskatchewans alone took 208 casualties, including their commander. The Essex Scottish Regiment was up next. Lance-Bombardier Munro remembered: “its our men against tanks – the best tanks in the war…at the same time we’re facing heavy mortar and artillery fire.” A retreating South Saskatchewan yelled, “It’s bloody suicide up there!”

Despite their bloody losses, the tough Canadians gritted their teeth and kept fighting. The German versus Canadian duel continued throughout the night. Thunder boomed in the sky and rain poured in buckets over the war torn slopes. The ground turned into a quagmire. Unrelenting fire from their field guns enabled the Fusiliers Mont Royal to hold onto Troteval farm into the next morning. Artillery Captain Britton Smith remembers: “He’s [a tiger] so bloody close-only two hundred yards away–that each time he fires, the muzzle blast bang our ears together and flattens the grain all around us as the shot screeches overhead and a shower of sparks goes up from one of our tanks up on the hill…I put a battery of mediums on him and hammer him for about half an hour. I may not have knocked him out, but I’ll bet I loosened up the bowels of the crew.” The artillery fire coped with the enemy infantry but “when they begin coming with tanks, we realize the jig is up.” Renewed attacks by the Leibstandarte in the morning of the July 21st brought the Essex Scottish casualties up to 301. The regiment was only able to withdraw due to a timely appearance by the Canadian Black Watch alongside tanks of the 1st Hussars and Sherbrooke Fusiliers.

Goodwood had reached its end. Utilizing skillful fighting withdrawals, the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS defense had skillfully blunted the materially and numerically greater attack of the British 2nd Army. Oberstgruppenführer (SS-Colonel General) “Sepp” Dietrich, commander of the 1st SS Panzer Corps, also praised the hard toiling mechanics of the nearby German tank repair shops. He personally awarded them the Iron Cross Second Class. Poor weather that prevented Allied air support and poor British coordination and intelligence, enabled the Germans to achieve what was perhaps their greatest defensive victory of the Normandy campaign. They had inflicted over 5,500 casualties on the British 2nd Army and had destroyed 253 tanks. The British and Canadian sacrifices only extended the Allied bridgehead by only nine kilometers and failed to secure the vital crest of the Bourguébus ridge. Although the British-Canadians held most of the northern slope, only one of the five main tactical objectives, the village of Hubert-Folie, had been secured. The Germans had only lost 75 tanks during the battle, of which more than 40 of those were lost to airstrikes, and personnel losses were relatively light as well.

Incredibly, Montgomery calmly claimed that Goodwood achieved everything he hoped for, even though the original operational order listed Falaise as one of the objectives. Already on July 15th, however, Montgomery had changed Falaise to a target for reconnaissance units only, but then failed to notify Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) of the change. Probably Montgomery privately doubted that Goodwood would achieve a decisive breakthrough but publicly supported this notion to gain air support for the operation. A furious Eisenhower commented that the Allies could hardly expect to advance through France at the rate of 1,000 tons of bombs per mile! Even Churchill was disappointed.

In Montgomery’s defense, though, Goodwood drew the bulk of the panzer divisions away from the American western flank. More importantly, it diverted the deteriorating German supplies to the British sector. When on July 25th the American breakout of “Cobra” broke loose in the St. Lô sector, the Germans not only faced a better-planned and-executed operation but also lacked the supplies to sustain an effective defense.

L.H. Dyck’s unabridged Goodwood article, accompanying notes and sources is available at Ludwig H. Dyck’s Historical Writings: Operation Goodwood: Epic Armor Clash in Normandy