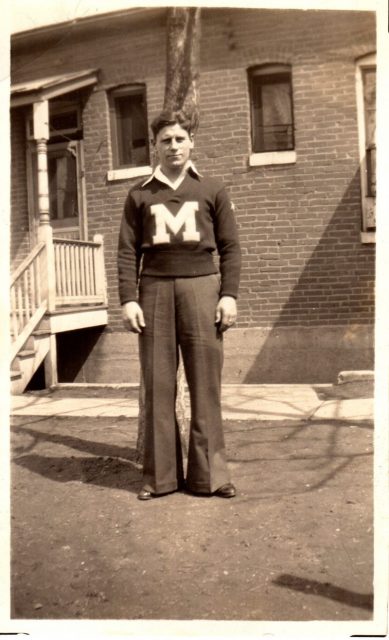

Coming of age in a community of St. Louis referred to as the “Patch,” Fred Hoechst Jr. graduated from high school only to experience the employment difficulties of the grim period known as the Great Depression.

The scarcity of jobs not only motivated the young man to enlist in the military, but also placed him aboard a naval vessel that would help search for a famed American aviator who went missing.

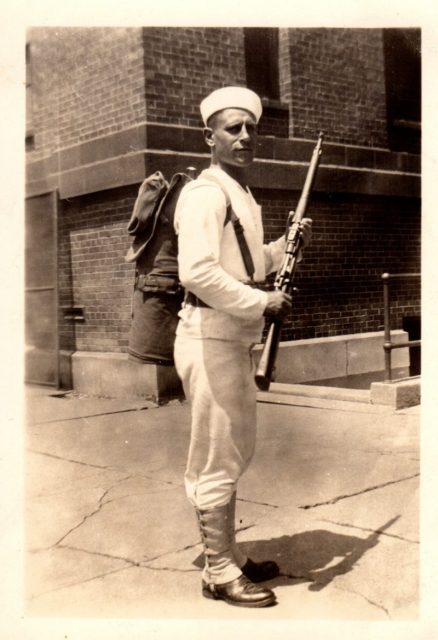

Naval records preserved by Hoechst’s family indicate the 21-year-old made the decision to embark upon a four-year enlistment in the U.S. Navy on May 5, 1936. The first stop in his new career choice was boot camp at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago.

Upon graduating from boot camp, Hoechst acquired his first experience as a sailor when assigned to the USS Colorado (BB 45)—a battleship commissioned several years earlier, on August 30, 1923.

According to Naval History and Heritage Command, “From 1924-1941 Colorado operated with the Battle Fleet in the Pacific, participating in fleet exercises and various ceremonies.”

Joining the crew while Colorado was stationed with the U.S. Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Seaman Apprentice Hoechst began his climb through the enlisted ranks. He advanced to fireman third class in June 1937, learning to operate and maintain the boilers that provided the steam power for the vessel.

The following month, Colorado arrived at Honolulu during a one-month training cruise for Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps students from the University of California and University of Washington, as well as a number of distinguished guests. However, their plans were abruptly altered by the disappearance of a celebrated female American aviator.

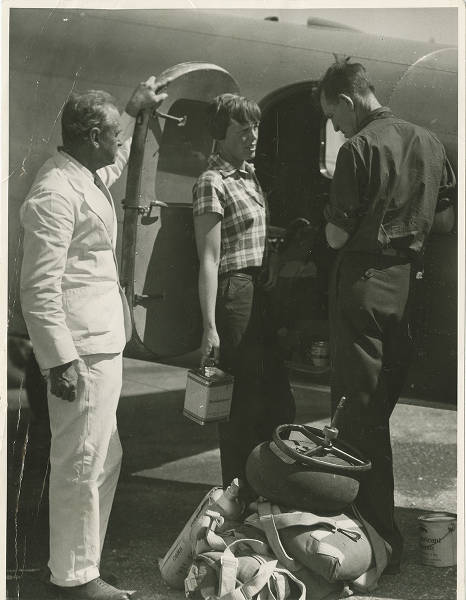

“On the morning of 1 July, 1937, (Honolulu Time) Mrs. Amelia Earhart…and her navigator, Mr. Fred J. Noonan, took off from New Guinea for Howland Island in the Lockheed plane known as a flying laboratory,” reported William L. Friedell, commanding officer of Colorado, in a report dated July 13, 1937.

In the years previous, Earhart merited the reputation as a living legend through her many aeronautical accomplishments. It was on this trip, however, that the aviation pioneer planned to achieve her greatest triumph by flying around the world.

On July 2, 1937, the day after her departure from New Guinea, “word was received in Honolulu that the Earhart plane had not arrived at Howland Island,” Friedell further reported. Hours later, Colorado received instructions to depart Pearl Harbor to participate in the search for the missing aviators.

“AMELIA LOST! This was the newspaper headline thousands of Americans woke up to on July 3, 1937,” wrote Candace Fleming in her book Amelia Lost: The Life and Disappearance of Amelia Earhart. She added, “And for the next ten days the lost flier stayed on the front pages as people grasped for any tidbit of information.”

Colorado was soon placed in charge of all vessels involved in the search. Although the impromptu mission was serious, it did not prevent Hoechst and a group of his fellow sailors from undergoing the transition from “pollywog” to “shellback” on July 7, 1937. This meant they were initiated during a special ceremony in recognition of their first time crossing the Equator.

“The USS Colorado arrived off Pearl Harbor early yesterday afternoon after participating in the Amelia Earhart search and after taking aboard supplies,” reported the Honolulu Advertiser on July 17, 1937. The ship ultimately discovered no traces of the aircraft, and for decades the disappearance remained a topic of investigation and debate.

While aboard Colorado, Hoechst traveled the world during Pacific and European cruises. His records reveal that he not only enjoyed sightseeing activities in his free time, such as the New York’s World Fair in 1939, but he also passed through the Panama Canal with the U.S. Fleet—comprised of 140 ships and 60,000 sailors—in the early weeks of 1940.

Hoechst remained in the Navy until March 1940, at which time he was discharged as a watertender second class. Having survived the closing months of the Great Depression while in the Navy, the veteran returned to St. Louis, got married, and went to work for the National Lead Company in southeastern St. Louis.

However, months prior to his discharge, Germany invaded Poland, which led to a stiffening American military posture and increased levels of national spending, which helped to spur an economic recovery.

Despite improving economic conditions, when the attack at Pearl Harbor occurred the following year the former sailor made the decision to leave his civilian employment and leap into the fray.

Hoechst has since passed away and is no longer able to share firsthand recollections of his military experiences, yet the words spoken by President John F. Kennedy at the U.S. Naval Academy in 1963 seem to summarize the fulfillment Hoechst acquired through his seafaring adventures.

Read another story from us: Pearl Harbor Vet Recalls Crying at the Sight of the Fleet

Kennedy remarked, “And any man who may be asked in this century what he did to make his life worthwhile, I think can respond with a good deal of pride and satisfaction: ‘I served in the United States Navy.’”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.