Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Prior to becoming president of the United States, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt entered political circles as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, but it would be his service with the 1st Volunteer Cavalry during the Spanish-American War that would secure his reputation as a leader—and help catapult him to the White House.

Yet one name that is often overlooked from the annals of Spanish-American War history is that of former Missourian, Colonel Jay Torrey, who is believed to have originated the idea for the Rough Riders and was later involved in a tragedy that cut short his military career and may have prevented his own path to the presidency.

Born in the community of Pittsfield, Ill., in 1852, an article appearing in the January 4, 1921 edition of The Columbia Evening Missourian noted that Torrey “was left an orphan while still a small boy” and later “went to St. Louis where he began selling newspapers, thus earning enough money to continue school.”

He followed the path of education and personal responsibility when he went on to attend Washington University, earning his law degree in 1876. For the next 14 years, Torrey remained in St. Louis and became active with civic groups and fraternal organizations, while also petitioning Congress to pass bankruptcy reform, which, according to law journals of the period, resulted in the “The Torrey bankrupt act.”

Torrey’s interests soon shifted to those of a more rugged nature when he left Missouri in 1890 to join his brother in Wyoming to establish the Embar Cattle Company. The American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming notes that although Torrey remained politically active by serving in the Wyoming legislative assembly, it was his idea to form a cowboy regiment that would earn him a level of national notoriety.

On February 15, 1898, an explosion occurred aboard the USS Maine—a U.S. battleship that had been sent to Cuba under the auspices of protecting the interests of Americans living on the Spanish-controlled island.

The responsibility for the explosion, which resulted in the deaths of an estimated 260 American sailors, was believed to have been a mine placed in Havana Harbor by the Spanish. Two months later, on April 25, 1898, war was declared against Spain, thus uniting against a perceived common enemy a country still healing from the wounds of the Civil War.

President McKinley issued a call for 125,000 volunteers and Torrey soon “laid his plans before the officials at Washington and they were approved and he was commissioned to organize a regiment of rough riders,” as his obituary appearing in the December 6, 1920 edition of the St. Post Dispatch described.

Commanding the second of three regiments of “cowboys,” the Kansas City Journal wrote on April 28, 1898, that Colonel Torrey’s Second U.S. Volunteer Cavalry (which became known as “Torrey’s Rough Riders”) would “be comprised of frontiersmen who have special qualifications in horsemanship and marksmanship.” (The first regiment was commanded by Colonel Leonard Wood with Teddy Roosevelt as his second in command.)

Newspapers throughout the U.S. continued to chronicle his preparations and on June 21, 1898, The Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah) reported that Colonel Torrey and his anticipated complement of “800 or more well equipped cavalrymen, mounted on the finest horses produced in the west,” would soon depart Cheyenne, Wyo., bound for Jacksonville, Fla., and eventual service in Cuba.

After loading on three separate trains (comprised of 12 cars each) to haul the men and an additional three trains (of 25 cars each) to haul the horses and equipment, the regiment began their southeasterly journey. Though they lost a soldier who fell to his death from the train in St. Louis, their journey was relatively uneventful until reaching Mississippi.

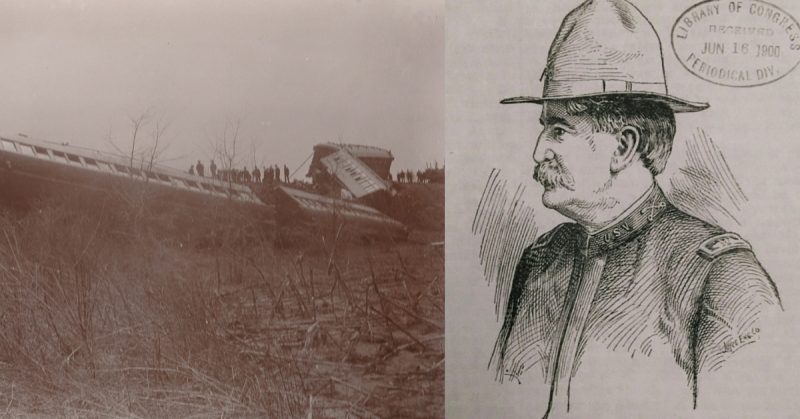

On June 26, 1898, Torrey’s opportunity to establish his mettle as a battle-hardened commander was dashed when, near Tupelo, Miss., the first train in their column stopped to take on water when the second train rounded the curve and struck the rear of the first train.

The accident resulted in a derailment of several cars, the death of five men and fifteen injuries, which included Colonel Torrey, who had to remain on crutches for several weeks due to injuries sustained in both his feet.

Several days later, Torrey and his group of Rough Riders finally made it to camp in Jacksonville, Fla., where they remained for the duration of the war while Roosevelt and his Rough Riders secured their reputation in Spanish-American War history during their charge up San Juan Hill in Cuba.

Shortly after his return from military service, Torrey was considered for nomination as running mate for President McKinley in 1900; however, Roosevelt eventually received the nomination, boosted by his fame from military service in Cuba.

Torrey returned to Missouri in 1906 and established a large farm near West Plains. Until his death in 1920, he remained an active participant in political and social affairs, leaving behind a legacy often shrouded by the legend of a fellow Rough Rider who later became president.

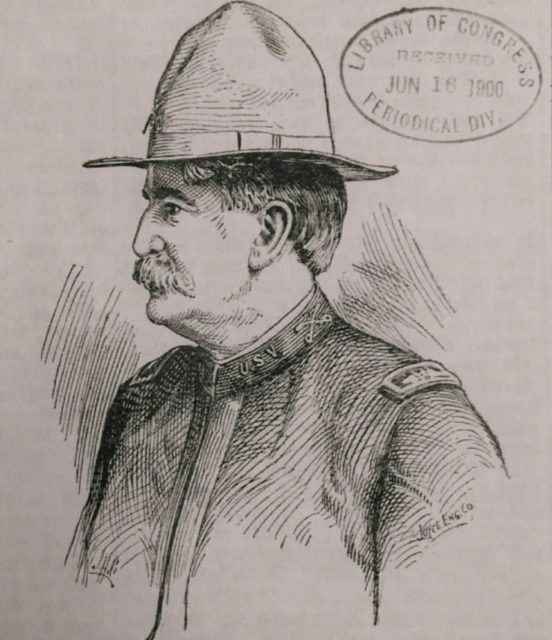

Elections have at times erupted in heated and inflated rhetoric, but the adoration the public maintained for Torrey during the search for McKinley’s running mate is described in an article appearing in The Colored American magazine on June 16, 1900, in which the editors noted a common perception of Colonel Jay Torrey as “a man of the people.”

“(He is) not a man who confined his patriotism to ‘hot air’ during the recent war, but one who put on a uniform; not a man from Wall street, but from the West. The man named thus far who fills this bill and who perfectly answers the demand of the times is Jay L. Torrey.”