War History Online presents this Guest Article from Jeremy P. Amick

As the U.S. Army Center of Military History notes, the state of Missouri suffered the loss of 8,003 of its citizens during the Second World War, leaving few families untouched by the fight for freedom. Yet such statistics often fail to reveal the personal consequences of these fatalities—the spouses and children left behind to grieve for their loved ones.

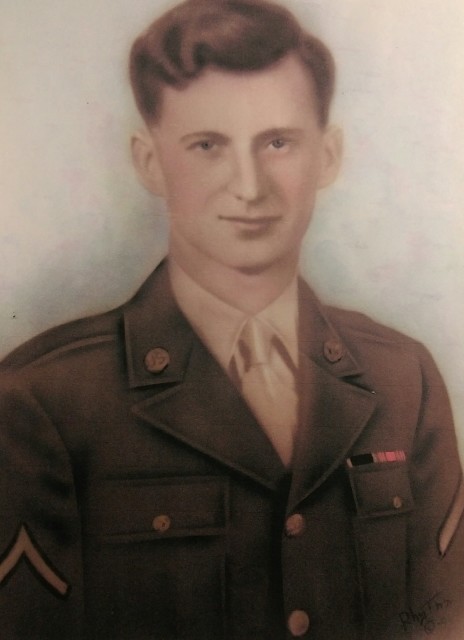

Born June 17, 1915 in Lohman, Mo., Wilbert Linsenbardt was a small boy when the country entered the tumultuous events of the First World War. Though many years would pass before the sequel to this deadly conflict unfolded, Linsenbardt began to lay down his roots with hopes of building a family.

“My father was the eldest of six children,” said Wilberta “Willie” Wright, Linsenbardt’s daughter. “The story goes that my father was in Jefferson City when he saw my mother in a drugstore and was immediately smitten by her. They had a whirlwind courtship and married in November 1941,” she added.

Married life began pleasantly for the new couple; however, a month following their marriage, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, an event that forever altered the lives of many young men and women throughout the United States.

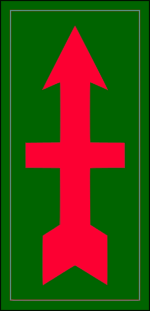

Wishing to do his part in support of the burgeoning war effort, Linsenbardt enlisted in the Army on January 8, 1942. He completed his boot camp and, after additional stateside training, was assigned to Company A, 128th Infantry Regiment under the 32nd Infantry Division (Red Arrow Division), with whom he was sent to the island of New Guinea.

The division became part of General MacArthur’s plan “to strike back (against the Japanese), to start back on the long road to liberate the Philippines and ‘on to Tokyo,’” so described Francis Miller in “The Complete History of World War II.”

Located off the northern coast of Australia, New Guinea is the second largest island in the world and played host to the Battle of Buna. Beginning in November 1942, the battle was part of the New Guinea Campaign, lasting more than two years and resulting in thousands of casualties, many of which were not the result of enemy aggression.

“Disease thrived on New Guinea,” notes the 32nd Division Association website. “Malaria was the greatest debilitator, but dengue, fever dysentery, scrub typhus, and a host of other tropical sicknesses awaited unwary soldiers in the jungle.”

No accounts of the island during this period paint a picturesque scene for Linsenbardt and his fellow soldiers, who, if able to survive the attacks against a well-entrenched foe, might very well succumb to the plagues harbored in the jungle.

“When I was born, my parents had been married scarcely a year, and my father was in Australia, I believe, en route to New Guinea after training at Camp Roberts in California,” said Wright. “At the urging of my Aunt Ella Schubert, I was named Wilberta for him since he was away fighting the war.”

History demonstrates that events unfolding on the island appeared grim from the earliest stages, as the 32nd Infantry Division made its coastal advance; many of the soldiers lacked proper jungle training and scores of men fell victim to both Japanese machine guns and the illnesses thriving in the jungle environment.

In a letter dated February 26, 1943, Captain Sheldon Darmelly, commander of Linsenbardt’s company, advised the soldier’s father of an outcome that many parents were to discover through the seemingly callous means of correspondence.

“May I offer my deep sympathy for you in the loss of your son, Wilbert G. Linsenbardt, in New Guinea, December 5, 1942,” explained the captain. “He was leading an attack against heavily defended Japanese positions when instantly killed by enemy fire.”

Leaving behind a wife of scarcely a year and daughter whom he had never met, Linsenbardt’s remains were transported to the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines—a 152-acre site that serves as the final resting site for 17,202 World War II dead, most of whom lost their lives during operations in New Guinea and the Philippines.

“My mother used the insurance money she received from the Army to buy a house on Dunklin Street in Jefferson City where I was raised until she remarried in 1953 and we moved to a larger home,” said Wright, who went on to graduate from Jefferson City High School in 1960.

In later years, Wright said, she perpetuated her family’s legacy of military service when she married her husband, John, who spent 26 years as a pilot with the U.S. Navy.

Though she never received the opportunity to meet her father, Wright affirms she has learned much about the man who gave of his life on an island thousands of miles from home by listening to stories shared by friends and family.

“They never really talked about (my father) when I was younger,” said Wright, “because it was really a difficult time for the family. But as I got older, his siblings would tell me about him … how he was very well-liked by everyone.”

She added, “While I was growing up, I had several uncles who had fought during World War II, but nowadays, I don’t think many of our youth really know of someone who has served in war. This is why I really believe it is important to remember people like my father … because the younger generation really needs to be introduced to those who have sacrificed so much for them.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.