War History Online presents this Guest Article from Alf R. Jacobsen

The Royal Navy and Bletchley Park helped save Murmansk for the Arctic convoys

In the hot and nerve-racked summer of 1941, while the Nazi panzer armies raced towards Moscow, the codebreakers at Bletchley Park gradually learned to master the complex German naval Enigma machine. Radio listeners at Scarborough Head intercepted an increasing number of radio signals between ships and harbormasters in the High North. Studying the decoded messages, commander Norman Denning at the Admiralty’s Operational Intelligence Centre in late August suddenly realized that a major German supply operation was underway the Arctic Ocean. Heavily escorted German troopships and cargo vessels left the port of Tromsoe in Northern Norway heading for Kirkenes close to the Soviet border every third day as if run by clockwork.

Denning’s deduction was correct. Hitler’s favorite general Eduard Dietl and his famous mountain corps had been ordered to conquer Murmansk, the railway to Leningrad and crush all opposition in Northwest Russia. So far, Dietl had failed. Crossing the trackless and uninhabited tundra, his soldiers had become stuck in the Litza valley, only 50 kilometers from Murmansk, and suffered terrible losses in bloody hand-to-hand combat with the Red Army.

To save his old Nazi comrade from a humiliating defeat, Hitler had intervened and sent two fresh regiments and the well-trained 6th mountain division as reinforcements to Dietl. The division had under the ruthless general Ferdinand Schörner recently conquered Athens and planted the swastika on top of the Acropolis. Its 18 000 men would join Dietl’s corps for the final push, starting 8 September. The decrypts told Denning that the movements were underway. He had to act swiftly with the means at hand.

As a first emergency measure, Churchill had answered Stalin’s increasingly desperate calls for help by sending a Royal Navy squadron of cruisers and destroyers under Rear Admiral Philip Vian, two long-range submarines and a wing of Hurricane fighters northward.

In the early morning hours of 28 August, while hiding among the inshore islands close to the North Cape, Sladen on board HMS Trident picked up the first warning signal from Denning. ‘Signal stating convoys leave Tromsø every three days, last on 24th,’ Sladen wrote. ‘I should, therefore, have seen one yesterday.’

The submarine was at the end of its patrol, and only two torpedoes were left. Despite his disappointment, Sladen made an inspired decision. He decided to wait in the area for another 48 hours in case the Germans for one reason or another had changed their rhythm. His patience was rewarded. At 2 pm two days later – four hours before his private deadline ran out – he spotted smoke on the horizon.

The following attack was carried through with bravery and determination. Sladen penetrated the screen of escort vessels and fired his two remaining torpedoes at the convoy; the nearest enemy destroyer being only 400 yards away. Two troopships – the Donau II and Bahia Laura – with reinforcements for Dietl’s corps were sunk. More than 600 men were killed, and the 1200 survivors lost all their weapons and equipment.

The biggest effect was psychological. The tension among the German staff officers rose. They had dozens of other ships underway and feared future attacks. When Vian’s squadron a few days later in fog and darkness cut off the next convoy and sunk a German light cruiser, panic spread. The Army Command decided it was too dangerous to continue carrying troops along the coast. The ships were stopped and ordered to seek shelter in the nearest port. The 6th mountain division was sent ashore and ordered to march on foot to the front, 600 kilometers away, arriving in late October. When Dietl started his last big push on September 8th, no significant reinforcements had arrived, and he suffered another defeat.

Murmansk was saved as a future convoy port. During the next four years, it received more than four million tons of vital Western supplies from Allied ships, helping the Red Army withstand the German onslaught. Had Sladen and Vian failed, Schörner’s division would have reached the frontline in time. All the Russian reserves were spent, and Murmansk and the railway line might have fallen into German hands. It might not have been decisive for the final outcome, but it probably would have meant a longer and harder war.

The commander of the Soviet Northern Fleet, Vice Admiral Arsenij Golovko had great respect for the achievements of the two British submarines, which during three months of intense fighting sunk at least six ships, damaged a number of others and spread terror among the German staff officers.

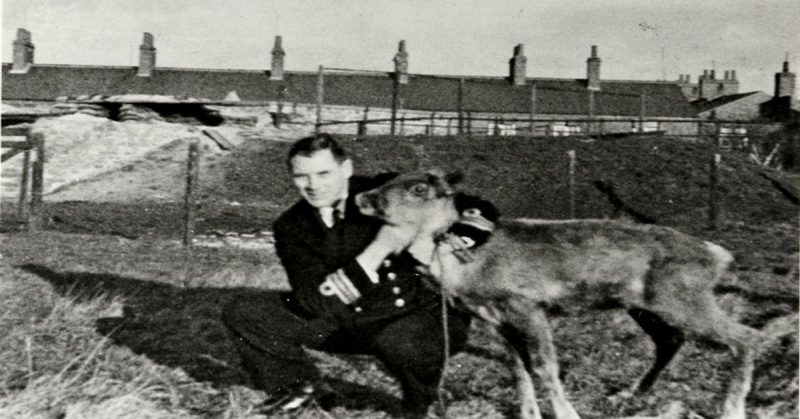

When HMS Trident finally left Murmansk on the 15th of November, Sladen was presented with a surprise farewell gift, a reindeer and a sack of moss. The reindeer was promptly christened Pollyanna (after the naval port of Polarnoje) and pampered with condensed milk and leftovers from the mess during the two weeks transfer voyage from North Russia to England.

Upon arrival at Blyth 30 November, the reindeer had put on weight and had to be hoisted ashore through the main hatch. She was given to the London Regent Park Zoo as a gift from the Russian to the British people and died peacefully five years later, in 1946.

This passage is taken from Miracle at the Litza by Alf R. Jacobsen, which is the story of Hitler’s first Eastern Front defeat in the Arctic. It is available now on Amazon.