War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

As author David Fiedler explained in his book “The Enemy Among Us: POWs in Missouri During World War II,” the state was once home to more than 15,000 German and Italian prisoners of war (POW).

Many of the camps where they were held have faded into distant memory as little evidence remains of their existence; however, one local resident has a relic from a former POW camp that provides an enduring connection to the service of a departed relative.

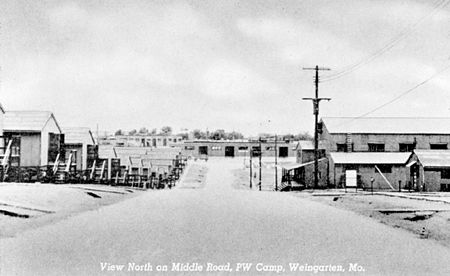

“Established at Weingarten, a sleepy little town on State Highway 32 between Ste. Genevieve and Farmington, Missouri, (Camp Weingarten) had no pre-war existence,” wrote Fiedler. The author further explained, “(T)he camp was enlarged to the point that some 5,800 POWs could be held there, and approximately 380 buildings of all types would be constructed on an expanded 950-acre site.”

Camp Weingarten quickly grew into a sprawling facility to house Italian POWs brought to the United States and, explained Jefferson City resident Carolyn McDowell, was the site where one of her uncles spent his entire period of service with the U.S. Army in World War II.

“My mother’s brother, Dwight Hafford Taylor, was raised in the community of Alton in southern Missouri,” said McDowell. “His hometown really wasn’t all that far from Camp Weingarten,” she added.

Although her uncle passed away in 1970, records accessed through the National Archives and Records Administration indicate he was drafted into the U.S. Army and entered service at Jefferson Barracks on November 10, 1942. After completing his initial training, he was designated as infantry and became a clerk with the 201st Infantry Regiment.

Shortly after Taylor received assignment to Camp Weingarten, Italian prisoners of war began to arrive at the camp in May 1943. Despite the challenges of overseeing the internment of former enemy soldiers, the camp experienced few security incidents and conditions remained rather cordial, in part due to the sustenance given the prisoners.

It was noted that many of the Italians were “semi-emaciated” when arriving in the United States because of a poor diet. The Chicago Tribune reported on October 23, 1943, that the prisoners at Camp Weingarten soon “put on weight” by eating a “daily menu … superior to that of the average civilian.”

Pfc. Taylor and his fellow soldiers, most of whom were assigned to military police companies, maintained a busy schedule of guarding the prisoners held in the camp, but also received opportunities to take leave from their duties and visit their loved ones back home.

“During one of my uncle’s visits back to Alton, he asked his mother for an aluminum pie pan,” said McDowell. “He then took it back to camp with him and that’s when he gave it to one of the Italian POWs.”

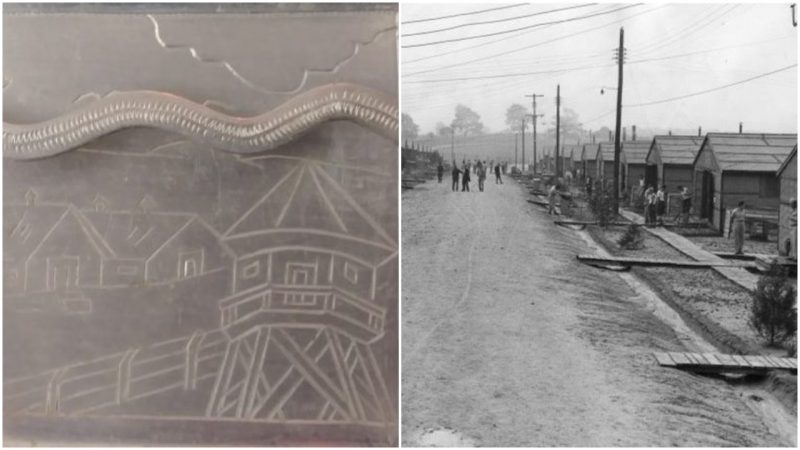

When returning to camp, one of the POWs with whom Taylor had established a friendship was given the pie pan and used it to demonstrate his abilities as an artist and a craftsman by fashioning it into a cigarette case. The case not only had a specially crafted latching mechanism, but was also etched with an emblem of an eagle on the cover with barracks buildings and a guard tower from the camp inscribed upon the inside.

“My uncle then gave the cigarette case as a gift to my father, who was living in Jefferson City at the time and working as superintendent of the tobacco factory inside the Missouri State Penitentiary,” stated McDowell. “It is a beautifully crafted cigarette case, but the irony of it all is that my father never smoked,” she jokingly added.

As McDowell went on to explain, her uncle remained at Camp Weingarten until his discharge from the U.S. Army in December 1944. The following October, the former POW camp was closed and many of the buildings were dismantled, shipped and reassembled as housing for student veterans at colleges and universities throughout the United States.

In the years after the war, McDowell said, her mother kept the cigarette case tucked away in a chest of drawers but since both of her parents have passed, she now believes the historical item should be on display in a museum.

Little remains of the once sprawling POW camp located approximately 90 miles south of St. Louis, with the exception of a stone fireplace that was part of the Officer’s Club. McDowell notes the cigarette case is not only a beautiful piece that serves as a link to the past, but represents a story to be shared of the state’s rich military legacy.

“I will someday donate the cigarette case to a museum for preservation and display, and I believe my brother, Harold McDowell, would agree. However, I want to ensure it is recognized for the treasure that it is and it is not simply thrown away,” said McDowell. “That’s why I want to tell the story of its creation … its history, so that its association to Camp Weingarten is never forgotten.”