War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Lars Erik York Gill

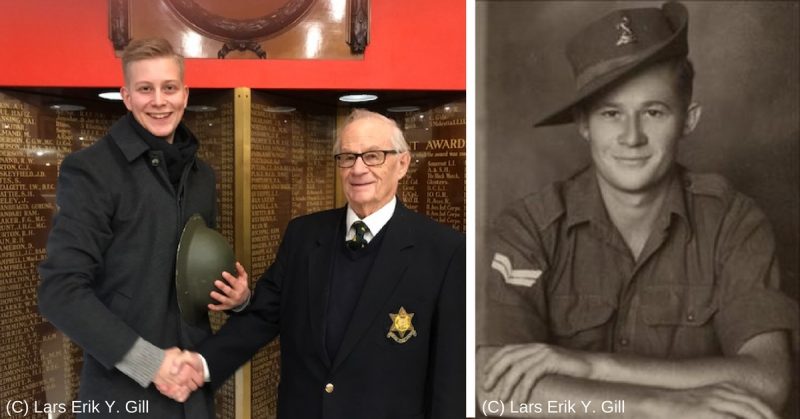

As one of the last voices of the British Army that fought in the Far East during WWII, Vic Knibb (93) recalls his time serving in Burma with the Royal West Kent Regiment where the weather, tropical diseases, and starvation proved just as hard as fighting a fanatical enemy hellbent on never surrendering.

By January 1942, Imperial Japan had started their own “blitzkrieg” in the Far East and the Pacific, by bombing the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and invading the Philippines, Wake Island, the Dutch East Indies and British Malaya, Hong Kong and Borneo.

The Japanese 15th Army, via neutral Thailand, invaded British Burma in January 1942, thus creating a buffer zone which divided Malaya and British India.

The Japanese plan was initially to conquer Rangoon, the capital of Burma, with its important seaport, thereby cutting off a vital supply line to China and to gain shipping access to the newly conquered Dutch East Indies.

Attacking over the Kawareik Pass in South-East Burma after overcoming hard British resistance from the 17th Indian Division, sections of the Japanese Army reached and captured the vital bridge over the Salween River, effectively blocking any possibility of retreat. This also meant that Rangoon would soon be surrounded by the enemy. On March 7th, the newly appointed Commander-in-chief of the Burma Army, Harrold Alexander, ordered the city to be evacuated after its oil refinery and port had been destroyed.

The remnants of the British Army in Burma retreated north, narrowly escaping encirclement.

In the north, the newly arrived Japanese 56th Division destroyed the Chinese 6th Division and managed to cut off the Chinese Army further north. This later led to the collapse of the entire Allied defensive line and there was little choice left then but to retreat further into the forested mountains of the Burmese north and towards the Indian border.

After the fall of Rangoon, the Allies tried to make a stand in the upper north of Burma after being reinforced by units from the Chinese Expeditionary Force. It did not help the situation that the Japanese themselves had been reinforced by two divisions released after the fall of Singapore in February 1942, and they quickly defeated the newly formed Burma Corps and the Chinese force.

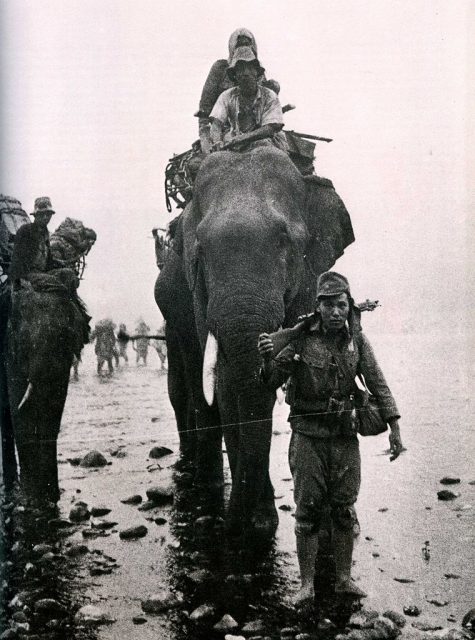

With supply sources cut off and with little food and ammunition, the Allied commanders finally decided to evacuate all forces from Burma back into India.

A difficult retreat then followed with thousands of refugees flooding the few roads available. It did not help matters that rumors of the war crimes perpetrated by the Japanese forces in Singapore and Rangoon had started to filter through, where the Japanese forces partook in an orgy of violence, terrorizing the civilian population.

By May 1942, the bulk of what remained of the Burma Corps had successfully managed to retreat to Imphal in India, fortunately just before the start of the monsoon season. Due to communications issues, however, almost none of the Chinese forces were aware of the retreat and were left facing the Japanese Army alone. Realizing the perilous situation they were in, the Chinese X Force under Chiang Kai-Shek made a hasty and highly disorganized retreat to India where they were later put under the command of American General Joseph Stillwell.

After the monsoon season, however, the Japanese Army did not renew their attack. Instead, they installed a puppet government heavily controlled by Japanese authorities.

On the Allied side, operations in Burma during the remainder of 1942 and into 1943 suffered a series of setbacks, and militarily, the level of frustration was high. There simply were not enough resources available with Britain fighting active campaigns in North Africa and the Middle East. Nonetheless, the Allies managed to gather together enough men and equipment to mount two offensive operations during the dry season of 1942-43. One of these was a smaller attack on the coast of the Arakan region to retake and occupy the Mayu Peninsula and Akyab Island which had important airfields on them.

The operation was a failure, in part because of the British Army’s inexperience of fighting in the terrain and climate of Burma at this point of the war, but also because of the heavy Japanese reinforcements that arrived from central Burma.

The other operation was considered highly controversial. The idea was for the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, otherwise known as the Chindits, under the command of Brigadier Orde Wingate, to penetrate Japanese frontlines and march deep into occupied Burma with only hand-carried supplies, the goal being to cut off the main railway running north to south. In all, over 3000 men set off to penetrate the Japanese lines.

By late 1943, the balance in Burma started to shift, with growing allied air superiority in the region together with vastly improved training, logistics, and equipment. Also, a change in leadership happened at this point with the creation of the South East Asia Command (SEAC) under the command of Lord Louis Mountbatten.

At about the same time that SEAC was established, the Japanese themselves created the Burma Area Army under Lt. General Masakazu Kawabe, which now also included the 15th and 28th Armies.

The 15th Army Commander Lt. General Renya Mutaguchi was very keen on mounting an offensive from Burma into India, a plan the Japanese Southern Expeditionary Army Group HQ in Singapore supported.

By this time, the British IV Corps had managed to push two divisions to the Chindwin River, with one division in reserve at Imphal, India. There were indications that a large scale Japanese offensive was about to begin and the commander of the British 14th Army, Lt. General William Slim, was planning to pull back his troops to make the Japanese forces fight with their supply lines stretched. However, the Allied high command misjudged the date of the Japanese attack and underestimated its strength. The Japanese 15th Army actually consisted of no less than three infantry divisions plus one independent brigade and a regiment from the Indian National Army, who had formed an alliance with the Japanese.

The Japanese crossed the Chindwin River on March 8th, 1944, and the 17th Indian Infantry Division was cut off. By some miracle, they managed to fight their way back to Imphal, an important crossroads to the village of Kohima and from there further into India. It was to be in early April 1944 that the Japanese 31st Division reached Kohima. Instead of isolating and bypassing the small British force there (which included the West Kent Regiment) the 31st Division commander Lt. General Kotoku Sato decided to press on into the village.

The now-famous siege of Kohima lasted from April 5th to the 18th and included some of the most brutal combat of the entire campaign. By the 18th, the exhausted British 2nd Division (reinforced) in Kohima was relieved by the Indian XXXIII Corps under Lt. General Stopford. ¨

The British 2nd Infantry Division began a counterattack and by May 15th had managed to press the now exhausted Japanese forces off Kohima Ridge.

The Japanese force was at this point in full retreat. With their supply lines near to breaking point, they had no food and little or no ammunition. The following Japanese retreat back to the Chindwin River would prove to be an utter disaster and the greatest defeat for the Japanese in their history with over 60,000 men killed in action, from disease or through starvation. In addition, over 100,000 or more were wounded. The Japanese soldiers that survived this massive retreat would later name it the “road of bones”

Meanwhile, during the early period of the Burma Campaign Vic Knibb had been living in Hampton Court, London, serving in the British Home Guard as a dispatch writer since the age of 15.

At this point in the war, Britain had started drafting able-bodied men for their armed forces. On January 4th, Vic turned 18 years old and instead of waiting to be drafted, he decided to volunteer for the Army on his birthday.

“…I was called up in my Home Guard uniform and volunteered and went in by March 1943 at the age of 18. You got a different number if you were a volunteer. You got a `14 number` against being a draftee. You were asked where you wanted to go, which branch, and they put me in the infantry, so I became an infantryman.”

Vic spent his first six weeks training in Derby with the Surrey Regiment and thereafter twelve weeks at the barracks in Canterbury attached with the Buffs (Royal East Kent) Regiment which he remembers as a tough, but enjoyable time.

“It was a broad training which was very good and very necessary at the time. We learned how to operate the Bren Gun and hand grenades and two-inch mortars as well, but you did not necessarily carry one. You spent some time at the rifle range, but not a great deal.”

In August that year, Vic was sent on a ten-week mortar course in Shrewsbury to learn how to operate the British 3” mortar, which was followed by a posting to the East Surrey Regiment at Hunstanton.

“… and then it was on my record, so wherever I went they put me in a mortar platoon”

His battalion then went to Northumberland and Vic specifically remembers the cold up there. It was going to be a short stay, however, as in early February 1944 Vic`s unit left Liverpool by ship, not knowing where they were going.

“We went to Gibraltar, and when they did not let us off the boat by the Suez, we guessed we were going to India. Then we arrived in Bombay”

Vic spent six weeks in Dolali, a jungle camp just outside Nasik City, which was a large transit city for troops going in and out of India. At the time, and particularly here, the anti-British feeling had been growing, and it did not help that a famine in Bengal had led to as many as 3 million people starving to death.

“We had to have wire over our lorries because they used to throw stuff at you at Nasik City”

After a speedy transit thought Nazik City and a four day train ride to Calcutta, Vic`s unit flew to Imphal were he was informed that he was to join the unit that he would stay with for the duration of the war: the 4th Battalion, Queens Own Royal West Kent Regiment who were based near the 57th Milestone just outside Kohima. The West Kents, also called “The Dirty Half Dozen” had participated in the grueling fighting against the Japanese 15th Army during the siege of Kohima in April, although the new replacements were not told about it.

“I was one of the first recruits. But there were not many of them left, and those that were left were shell-shocked.”

The Regiment was moved to Johart in Assam, India, where much reorganization and training took place. At this point, Vic got a week of leave in Calcutta. After returning, the regiment got the order to load up on trucks and then traveled for several days to the front line near the village of Meiktila to join the fighting.

By now, the 11th East African Divison had advanced down the Kabaw Valley in north-west Burma near the Indian border. The 5th Indian Division, to which the 4th Battalion West Kent Regiment was formally attached to, had advanced along the mountainous Tiddim Road on their way to the Chindwin River. It was not far from here that Vic would get sight of the enemy for the first time.

“The first contact with the enemy was when we came to a railway line and we sort of bedded down, and then we crossed the railway line. We went and dug a slit trench for protection and in that trench I found a coin, which I put in my pocket and had to the last day I left Burma.

“I`m not terribly superstitious, but I was extremely lucky! That night at about 02:00 in the morning, I went out for my two-hour watch and the fellow before me said he had taken the pin out of a grenade, a Mills bomb, and gave me the grenade. Then I suddenly realized that if I took the base plate out and the fuse I could let go as it was hurting my hand. During the night, we heard some Japs quite close, talking, but we did not do anything in particular. That was the first night, but there were other occasions just after where they came across us and they fired at us. Rifle fire. Frightening …”

At this point, the Imperial Japanese Army was in full retreat after the Allies had launched several larger offensives into Burma. On the Southern Front, the XV Corps had resumed its attacks on Akyab Island. This time, the Japanese forces, lacking essential supplies, were far weaker and were forced to retreat, resulting in the XV Corps occupying the island without resistance.

In addition, landing craft that had been previously needed in Europe had now arrived which led to several amphibious operations including the capture of Ramree and Cheduba Islands where vital airfields were constructed.

In late 1944, on the Central Front, the British 36th Infantry Division made contact with Lt. General Slim`s 14th Army in Northern Burma.

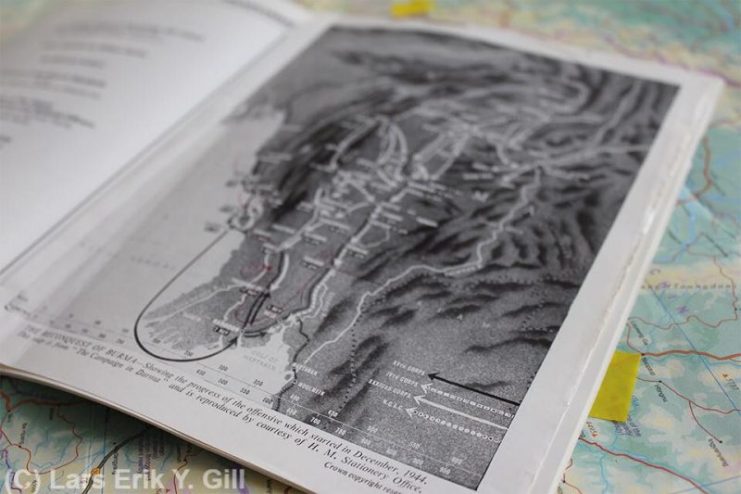

The 14th Army, consisting now of the IV Corps and XXXIII Corps, made a large main offensive into Burma. In early January 1945, XXXIII Corps reached their target of the Irrawaddy River, not far from Mandalay, where they met heavy Japanese resistance. Vic Knibb, the number one on his platoon’s 6” mortar number six found himself in the thick of it. His job: carrying the mortar base plate and sights. His number three carried the barrel, and four and five carried the mortar bombs.

“You did the sighting, ducked down and put the thing in the barrel.”

In addition, Vic remembers the rifle he also carried, a .303 caliber Lee Enfield No.4 with the aperture sight.

As the West Kents of the 5th Indian Division pushed towards Rangoon, Vic remembers the intense combat he took part in:

“… most of it were in the dawn or dusk when they used to appear. They used to yell `Johnny we’re Chinese. We are coming to talk to you` and they would lob a grenade at you if you did not shoot them first, but you used to shoot them first, you did not wait. They were quite happy to die, which we thought damn stupid. It was ingrained in them since childbirth and upbringing. The Japs were very brave to the point of stupidity. They knew how to follow orders and we did as well.

“I did not have hand-to-hand combat, but they were very close. You could see them sitting in a trench trying to throw grenades into your mortar pit because with a mortar you have a four-by-four foot square pit where you had the mortar and they were trying to throw grenades into it. And they were successful at times … Trying to rush our positions.”

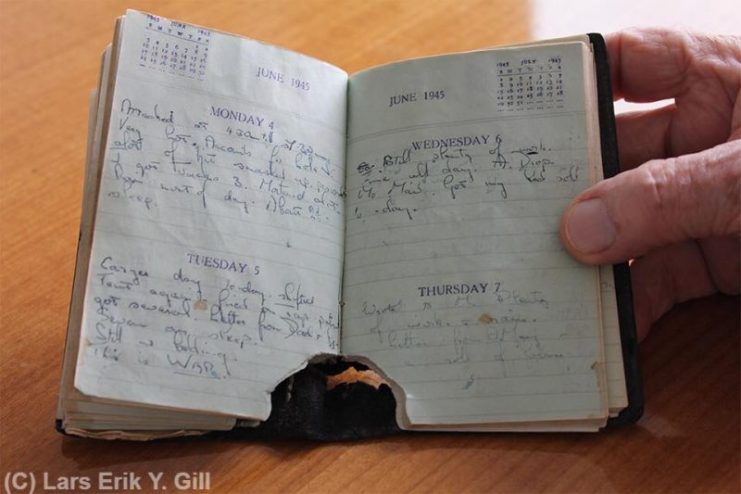

The fighting that took place would result in some of the most violent and vicious combat experiences of World War II, and the hatred towards each other for both combatants ran deep. At one point, during an encounter with Japanese forces, a bullet penetrated the haversack Vic was carrying, going through the diary he had in it and exited out the other side, missing his neck by inches!

The Japanese were also notorious for executing and torturing prisoners so waving the white flag was in many cases not an option for Allied soldiers, even when Vic’s company was surrounded for three days in the small village of Monshua.

“We knew what they had done to the women in Rangoon and other places and we never took any prisoners. As far as we were concerned, we just wanted to exterminate them all. All of them …”

For four months, Vic and his unit were at half rations until they reached Rangoon. Fighting in the jungle also carried the risk of tropical diseases that could be as hard an enemy as the Japanese themselves.

“Dysentery, malaria, yellow jaundice, you name it we had it. When we got close to Rangoon we had been on half rations by air and were covered in sores and ulcers.”

Vic was lucky and did not contract malaria, but did suffer from dysentery several times, and was later hospitalized for yellow jaundice. It’s estimated that over 12,700 British and Commonwealth troops died of disease during the Burma Campaign. Vic vividly recalls losing many friends to illness.

“When we arrived at Rangoon we had little ammunition and no food. We had broken down vehicles and if the Japanese had stopped, they could have whipped us out. But as luck would have it and as troops came in from the south and we came in from the north, the troops from the south were able to provide us with food. We were down to no first aid or anything. We were in really bad condition.”

Advancing along the hot, humid, and dusty roads of Burma also took its toll on the troops that had the task of clearing vast areas of retreating enemy soldiers. By this time, starving Japanese troops were desperately trying to find their way back from their old front lines. All the way from India bodies of Japanese soldiers lay strewn across the roads, in the villages, and in the bush.

“We would use lorries and then go off the main road by foot. We would do about 50 miles and then go off and clear the area, then we would go on again. There had been weeks where we had been up all night, two or three hours sleep and marching all day.”

Vic recalls a grueling march that really took its toll on the men and how, in true British spirit, bagpipes were heard at the front of the column.

“When we did a thirty- mile march we had a piper to bring us in the last five. That was actually the only time I saw a piper.”

“We also did come across Japanese, they were stragglers. They would try to come across and get from the west to east and we were in the road they wanted to travel down or cross. In the villages, they would rest or try to get food. We were occupying those villages and they would try to come through during the middle of the night or whenever. At times, you just saw four or five at a time and you would try to sort them out. When we came to a village we would get one of the locals to pull up the water and drink some of it so you knew it wasn’t poisoned by the Japs.”

Living in such an environment for a long period of time took its toll psychologically on the men. Basic sanitation equipment, clean water, and food were lacking. Staying dry was always a problem in the tropical environment, and home often seemed very far away.

“You did not know what on earth was happening or where you were. You were more interested in getting some cigarettes and some food and some water. We just confronted what happened … Your clothes did not last very long, they rotted away. Your boots fell apart. At one point I even wore a pair of Japanese boots. You were down to just very basic stuff. I mean, you drank water that had bodies in it … you know… We did not get it, basic supplies. At one point we only had one tank (in our outfit). We were living for the day and in the minute, because you never knew what the next hour could bring.”

In the middle of this hellhole, Vic recalls how his time in the boy scouts served him well living in the jungle, where others had a really hard time adapting to the tropical environment.

“What I learned in the scouts were very helpful to me. I made fire in the rain, in the monsoon and got something hot to eat. Basic skills. How to keep yourselves warm and dry, and how we used to make a bed out of bamboo quite quickly to get yourselves off the ground. Because otherwise you lay wet on the ground or slept up a tree.”

Improvising for food was also a common thing to supplement the already small rations.

“Oh yeah, well more than improvise, we used to go thieve from the Burmese. We were hungry. When we came to a village, we used to wander around the village until we found some rice. We were hungry, we would do anything.”

As Rangoon fell to the Allies, a new 12th Army HQ was formed from XXXIII Corps to take control over all units remaining in Burma. The Japanese 28th Army, after withdrawing from Arakan and fighting the XXXIII Corps all the way down the Irrawaddy Valley, had fled to the hills near Sittang River with the plan of rejoining the Burma Area Army. To make it possible, the 33rd Army made a diversionary attack, mustering only one small regiment across the Sittang River. After one week of fighting against British positions, both sides retreated. The 28th Army attempted their breakout, but ended in disaster as heavy British artillery were pre-sighted on the roads the Japanese had to use. The result was nearly 10,000 additional casualties for the already depleted Imperial Japanese Army.

By late April 1945, the Japanese High Command in Burma knew that Rangoon could not be held. Despite his orders from Tokyo, Lt. General Hyotaro Kimura withdrew his forces from Rangoon. On May 6th, the Battle of Rangoon officially ended as the 26th and 17th Indian Divisions made contact with one another. In all practical terms, it meant the end of the Allied campaign in Burma, although Anglo-British troops would continue to hunt down Japanese stragglers trying to escape to Thailand. On July 26th, the remaining 28,000 Japanese troops of the 28th Army withdrew across the border to Thailand under constant harassment from Allied aircraft.

On August 15th, 1945 (VJ Day), the Japanese finally surrendered to the Allies after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima on August 6th and Nagasaki on August 9th and the Soviet Union declaring war on Japan the same day. Japan’s acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration was broadcast by Emperor Hirohito himself on Radio Tokyo to the Japanese people.

“We got to know about the bomb. We were delighted because as far as we were concerned, we wanted to go home. We never thought about the long-term consequences of the bomb. We had no conception on what effect it would have on the Japanese or the world … thank goodness its over and we’re alive! You had no feeling for them at all.”

In Rangoon, a peace conference was held in Government House, where Japanese officials surrendered the city to the British and Vic Knibb was part of it. Vic’s unit was marched to a barracks area and given clean kit and clothes and the souvenir of a lifetime slipped away from his hands when he helped take some of the Japanese officials off the plane.

“When the Japanese surrendered they flew in and I took the fifth man off the airplane. I had to take the sword from him, he did not want to, but I said ‘give it to me’. I had to pass it on to an officer, and never saw it again. I wasn’t an officer so …”

The diary entry for June 5th, 1945, ends with his words: “This is WAR”. Photo: Lars Erik Y. Gill.

“I was in the peace conference in Rangoon, in the conference room, and I joined the conference armed with a Tommy Gun. I wasn’t told what to do with it. I had never used a Tommy Gun before. I remember standing there in my hat and there was a picture of the back of me taken in the conference room in Rangoon! Because of the badge on the hat I knew it was me. It wasn’t much of a conversation. You (the soldiers) really did not know what was happening. There wasn’t any discussion why you were standing there, it was just an order. The Army did not waste time talking about things.”

Following the Japanese surrender in Burma, Vic later spent Christmas of 1945 in hospital after he once again fell ill to yellow jaundice. The 4th Battalion West Kent Regiment was disbanded in January 1946 and that same month, Vic volunteered to join the 1st Battalion Nigeria Regiment of the Royal West African Frontier Force as an NCO. After 10 weeks and clashing with the Regiments South African officers, he was sent home for demobilization. The trip home was on an American Liberty Ship and was, in his words, “highly uncomfortable to say the least”

Vic demobilized in Chatham in the May of 1946 as a Lance Sergeant.

Upon returning home to England as one in over a million military men that had fought in Burma, life soon became very difficult. Jobs were hard to get, food was scarce, and London was in ruins after years of terror bombing by the Germans. Normal life still seemed so far away.

“When you got home you had to get a job. Get somewhere to live unless you lived with your parents. You hadn’t got much money. You hadn’t got a trade. Your education had stopped basically. Life became very difficult for the first three or four years. You wanted to get married and get a normal life. We were still very heavily rationed when we came home. I used to thief ducks off the river because we were hungry. So life was very difficult trying to get work as thousands of men were returning and everyone wanted jobs. There wasn’t the equipment or factories, I mean London was desolate. Square miles of nothing left at all, especially in the East End. You couldn’t believe it!”

Later in life Vic would become a carpenter and would work for several larger construction companies in London, ending up as foreman and working on many of the city’s most iconic and famous buildings. He would do this for a living until the day he retired.

In retrospect, the Japanese invasion of the Far East in late 1941 and early 1942 in many ways meant the beginning of the end of the British Empire. The Japanese invasion of India in 1944, although highly optimistic, was undoubtedly a wake-up call for the British and Commonwealth forces in the Far East. Britain relied heavily on the resources and manpower of its colonies during these difficult years, India perhaps being the most important.

“The majority of them (Indians) were brilliant people and very helpful. If it hadn’t been for them we wouldn’t have won!” Vic says.

Japan had a lot to account for at the end of the war in the Far East and the Pacific. The Japanese Armed Forces systematically murdered millions of non-combatants, including prisoners of war (POW). Over 20 million Chinese died during the Japanese occupation from 1937-1945. According to the Tokyo War Tribunal, the death rate of Allied POWs in Japanese camps was 27%, which was over seven times higher than the number of deaths in the German POW camps in Europe. Forced labor was also used, the most famous case of which was the Thai-Burma Railway (“Death Railway”) where over 90,000 civilian slaves and 12,000 Allied POWs had been worked and starved to death, or murdered.

Few of the war criminals responsible for these and many other crimes against humanity were ever prosecuted. Forty trials took place in Rangoon, Mandalay, and Maymyo in 1946 and 1947. The eighty-five defendants were charged and found guilty of violence and murder of Allied POWs and local civilians. The vast majority of them received jail sentences of 10-15 years and most were released by the early 1950s, serving little time for their crimes.

Also by this time, the balance of power in Asia had shifted dramatically. Both India and Burma, the countries that British and Commonwealth soldiers had fought to liberate from the Japanese, had been cut loose from Britain, having gained their independence in 1947 and 1948 respectively.

What drove men like Vic Knibb to join up to fight for God, King, and Empire more than 70 years ago was the desire to try their very best to help the war effort and save Britain and her position in the world.

“It was a lot more of that (patriotism) and the spirit of helping. Now it’s very much an individual’s interest. It’s another world … it was a different world back then.”

Also, coming to terms and forgiving the former enemy could be hard at times, even though so many years have passed by.

“I think I met one briefly (a Japanese veteran). So much time has gone by and they were conditioned to do what they did. It’s a cruelty streak in them and the Germans, which I detest, but other than that they are human beings as far as I’m concerned. If I meet them now I will talk to them, but I don’t make a point in meeting them. I’m lucky I survived, you know…”

As the writer of this article, I have been amazed over and over again by Vic’s incredible story and by the person he really is. As I left the interview we took a photo together and I thanked him for what he did, fighting for freedom in that not too distant past.

He looked at me, shook my hand and with a smile he said: “My pleasure.”

“WHEN YOU GO HOME, TELL THEM OF US AND SAY:

FOR YOUR TOMORROW, WE GAVE OUR TODAY”

British Empire WWII Memorial to the fallen at Kohima, India.

By Lars Erik Y. Gill, 24.04.2018