When endeavoring to tell a story that concerns behind-the-lines raids, partisan armies, and epic journeys deep into enemy territory, one invariably bumps up against the shadowy world of intelligence. Any “special operation” will have some ties to this secretive, murky arena of warfare.

The mystery men with their hidden agendas pop into the light fleetingly to give Special Forces soldiers their orders and their targets, after which they slide back into the shadows.

WWII was no different. My new book, SAS Italian Job, tells the story of two maverick Special Forces commanders and their private army of Italian partisans as they attempted one of the most daring raids of the Second World War.

Their audacious plan was to attack the German 14th Army headquarters, thus creating chaos in the enemy ranks just before the big push by the Allies to liberate Northern Italy. It was a mission that would be fraught with danger, adventure, tragedy, and betrayal.

In northern Italy in early 1945, legendary SAS commander, Major Roy Farran, and Captain Mike ‘Wild Man’ Lees of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) (Churchill’s secretive “Ministry for Ungentlemanly Warfare”) would unwittingly step on the toes of British Intelligence and clash with their own government.

While they were trying to fight the war as they believed it needed to be fought, they were increasingly confronting someone else’s shadowy agenda.

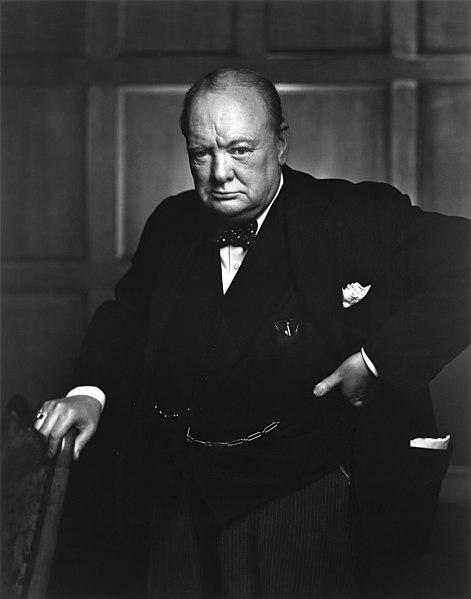

Up until late 1944, the Western Allies had a “come one, come all” policy concerning support to any resistance groups keen to fight the Nazis, no matter what side of the political spectrum they hailed from. Churchill was adamant: arms and support were to be provided to the resistance across occupied Europe.

Agents of the SOE, plus those serving with its American counterpart, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), were embedded within these groups. The agents would train the groups in weapons and explosives use, ambush, sabotage, and assassination techniques – anything they could contrive to turn a group of civilians into an underground army.

That doctrine was exactly what Farran and Lees followed in February and March 1945 when they armed and trained the Italian partisans, preparing to point their newly-hewn spear directly at the nerve center of the enemy.

Their idea was simplicity itself: cut off the ability of the enemy to command and control 100,000 troops by blowing up its headquarters and killing as many high ranking German officers as possible.

But unbeknown to them, the doctrine had been changed. Not officially, but quietly at the highest level. This resulted in a sudden truncation of supplies, transport, and weaponry for the Italian partisans. Almost overnight, positive press coverage for Italy’s (largely communist) resistance was ruthlessly suppressed.

Veteran Canadian war reporter, Paul Morton, had been embedded within the SOE and had risked his life to capture stories from behind enemy lines. He was shocked when his stories were suddenly spiked, never to see publication.

Worse still, he found himself blacklisted and cast as a liar, his career and reputation traduced. What had happened to cause such a volte-face by the British Government?

British Intelligence had spent most of its history tracking and combating two major groups. During the First and Second World Wars, its main target was Germany. However before WWI, and during the interwar period, they had reverted to their main target: communism, and stopping its spread.

With the end of WWII in sight, the Foreign Office and the British Government – who had never stopped spying on the Soviets – were dialing back the anti-German rhetoric in favor of taking a keener interest in their old enemy: Russia.

The strained relationship that had lasted since mid-1941 came to a close in the rush to shore up Western Europe against communism at the war’s end.

Trust in the alliance had been steadily eroding throughout the war. A watershed moment was the discovery in February 1943 of the bodies of thousands of Polish officers in the forest of Katyn, Russia.

When Russia had invaded the eastern half of Poland during 1940, they had rounded up anyone they thought might constitute a problem, such as military officers, priests, and university lecturers. These people were executed and buried.

Knowing full well that these executions had been carried out by Stalin’s NKVD (Secret Police), the Nazis used this to try and drive a wedge between the Western Allies and Stalin. The Polish Government in exile pushed Churchill to denounce the murders, but Churchill needed Stalin’s forces to keep fighting on the Eastern Front, so he ducked the issue.

However, Stalin’s lies concerning the fate of the thousands of Polish soldiers at Katyn were clear to British Intelligence: the Soviets had executed all those who would have offered any opposition to Soviet control. What was to stop them doing the same again in countries they had “liberated,” Allied intelligence reasoned?

Italy had the largest contingent of known communists outside of the Soviet Union, and it was a neighbor to the increasingly Soviet-dominated Yugoslavia. British intelligence reasoned that although Italy wouldn’t be liberated by the Soviets, it might fall into its sphere of influence.

The Western Allies had seen civil war erupt in Greece between right and left wing partisans, as soon as the Germans had been driven out. In the resulting power vacuum, the support and training the Allies had given the Greek partisans fuelled the civil war.

The Allies wanted to ensure they would avoid a similar situation in Italy, hence the British Government deciding to quietly cut support for the partisans. Requests for any large amounts of explosives or heavy weapons were to be denied, to limit those falling into the hands of the Italian communists.

Of course, this risked the partisans not being able to defend themselves against the Nazi occupiers. The SOE agents – known as ‘British Liaison Officers’ (BLOs) – embedded within such groups would also be vulnerable.

The death of the leader of SOE’s Operation Flap, Major Neville Darewski, in autumn 1944 under codename “Temple” was one of the first due to the covert change in policy.

Darewski had been calling for a resupply of arms to fend off a major enemy attack but to no avail. His exploits with the Italian partisans and the failure to re-supply them with weaponry would ultimately play a central role in his death.

Via Freedom of Information requests, I managed to open some British Government files that had been officially closed for 100 years. In those, I discovered that the British were willing to get into bed with some decidedly nefarious characters at war’s end, ones they felt would be useful in their plans for post-war Italy.

Even now, the contents are so sensitive that large tracts have been blacked out by the censor’s pen. But one file, closed until 2050 until I had it opened, spoke of a “proposal put to the Chief of Staff, to make contact with the Italian nobleman Prince Borghese, with the intention of encouraging anti-scorch measures and assisting in the maintenance of law and order.”

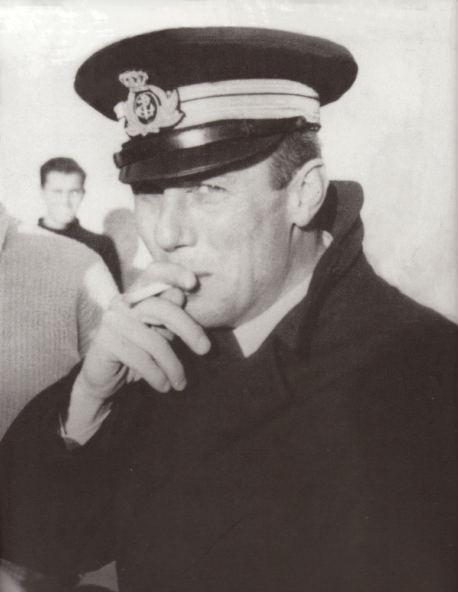

Don Junio Valerio Borghese, nicknamed “The Black Prince,” hailed from a titled Italian family with close ties to the Vatican. He’d served as a Naval Commander under Mussolini and was a hard-line fascist.

Upon the Italian surrender to the Allies in September 1943, Borghese had signed a treaty with the Kriegsmarine, Nazi Germany’s navy, raising an 18,000-strong force that would remain loyal to Hitler until the bitter end.

The proposed approach to Prince Borghese was to be made in March 1945, while we were still at war with the Nazis, and while Roy Farran and Mike Lees were in the field fighting at the sharp end.

British Intelligence was now playing a double game. By contacting Italy’s foremost allies of Nazi Germany, it was betraying its long-standing relationship with Italy’s partisans. This is but one example — there were many more.

As matters transpired, the communist wing of the Italian partisans quietly handed its weapons in at the end of the war, seeking to gain power via democratic means – if at all. Roy Farran and Mike Lees would successfully navigate this double game, to pull off one of the most audacious raids in the history of WWII.

Read another story from us: The Italian “Acqui” Mountain Infantry Division Disaster, Kefalonia, 1943

But they would not come away unscathed. Farran was inadvertently protected by the Americans when he was awarded a high-valor medal for the 14 Army HQ raid. But Lees would see his career in SOE disavowed and his future in the military, as well as his reputation, destroyed.

Damien Lewis’s new book, SAS Italian Job, features more about this story and you can order it here!

By Damien Lewis