War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

For many years, Wally Evenson stood behind a pulpit and shared with his congregations a number of accounts from the Bible while serving as a Lutheran pastor for several churches throughout the Midwest. What many might not have realized at the time is that the man who was instilling faith through recollection of biblical accounts had himself accrued many fascinating tales from his WWII naval service.

A native of Minnesota, Evenson explained that after his graduation from high school in the spring of 1944, it was the likelihood of his being drafted into the U.S. Army that motivated his decision to enlist in the Navy.

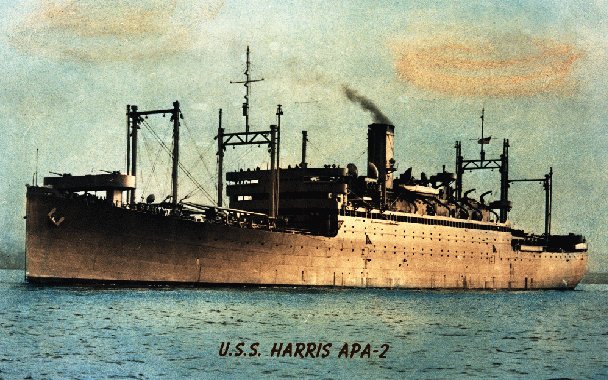

“They sent me to boot camp at Great Lakes (Ill.),” the veteran recalled. “From there, it was out to California to report for my first assignment, which was aboard the USS Harris.” He added, “The first thing I did was help get the ship loaded and ready to go to sea.”

Built in 1921 as a passenger liner and designated the SS Pine Tree State, the USS Harris was acquired by the Navy during World War II and reclassified as an attack transport. In line with its new designation and mission assignment, the USS Harris traveled to the state of Washington to board 1,500 infantry soldiers before sailing on to Pearl Harbor in May 1945.

Though more than three years had passed since the Japanese attack, Evenson recalls Pearl Harbor was “still in a very morbid, destructive condition with the (USS) Arizona lying on its side in the harbor and the airfield badly beaten.”

After a few days of leave, the crew of the USS Harris engaged in a couple of days of offshore target practice with the ship’s weaponry to hone their skills in shooting down aircraft. At that time, Evenson said, the threats from Japanese planes were prevalent for U.S. ships operating throughout the Pacific.

The ship then sailed to “catch up with a convoy of ships” bound for Okinawa, where the USS Harris anchored off the coast to begin unloading the infantrymen who had initially boarded back in the United States.

“While we were anchored off Okinawa and in the process of unloading the troops, kamikaze planes started coming toward the convoy one evening about the time it began getting dark,” recalled Evenson. “Me and another sailor were on a landing craft off the side of ship loaded with about 100 soldiers to take to shore,” he added.

As the veteran explained, they were instructed to keep their landing craft near the USS Harris for protection in case of an attack. As a protective measure, smoke pots were lit and placed around the ship to supplement the concealment of the approaching darkness.

In the dimness that followed, the landing craft floated around the opposite side of the ship while waiting for the threat to subside, which eventually required Evenson to hook a rope on a bar on the USS Harris in the near total darkness to ensure their landing craft did not float out to sea.

“We had to wait a half-hour or so for everything to settle down,” said Evenson. “Then, somebody yelled from over the side of the (USS Harris) for us to head to shore and finish offloading the soldiers.”

He further explained, “On the way into shore, our boat slid right on top of a reef and got stuck. The coxswain (operating the landing craft) was finally able to back off of it after several tries,” he added.

When the unloading of troops was finished, they returned to the USS Harris, which then hurried out to sea since word was received that a major typhoon was quickly approaching the region.

“We managed to avoid the biggest part of the storm but we did get caught in the edge of it,” he said. “When we returned to Okinawa, I remember seeing a lot of seagoing vessels that had simply been blown to pieces,” he solemnly recalled.

The years may have dulled his recollection of specific dates, but the former sailor recalls another profound moment aboard the USS Harris that occurred while transporting troops in the Pacific. Evenson was placed in the “crow’s nest”—a cage-like structure secured to mast of a ship and used as a lookout—with a pair of binoculars to scan the waters for evidence of submarine activity

“While I was up there a kamikaze plane came from behind, to my left,” he said. “It was dark out and the shore lights came on and then the shore guns started firing.” He exclaimed, “It was all kinds of fireworks but I don’t know if they hit him or not.”

Evenson remained with the Harris for several missions throughout the South Pacific and, following the Japanese surrender in August 1945, went on to perform several troop transport missions aboard the vessel. During the latter part of his military service, he was assigned to the USS Dixie until receiving his discharge in July 1946.

In the years after the war, he married, raised a family and enjoyed a career in the ministry. Yet his military service, though decades in hindsight, remains one of the highlights of the recollections he enjoys while relaxing in the unhurried pace of retirement.

“Back in 1944, I guess you could say that I was drafted—I had just turned 18 and received my greetings from Uncle Sam,” he grinned. “Then I joined the Navy and that certainly turned out to be quite an experience.”

Hesitantly, he added, “And to be honest, I can’t recall being scared during the war or ever seeing anyone dead or being hauled out on a stretcher. It was just a situation where you took every day as it came and had faith that the Lord would bring you home safely.”