War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

When Nicholas Monaco was a young boy growing up in the St. Louis area, his father was told that if he wanted his son to “grow up right,” he should get him a military education. Consequently, young Monaco went on to attend Christian Brothers College High School, completing his high school education and discovering that he “took to the military structure” through the school’s Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program.

Following his graduation in 1948, he then went on to attend the University of Missouri-Columbia, where he continued both his studies and participation in the ROTC program.

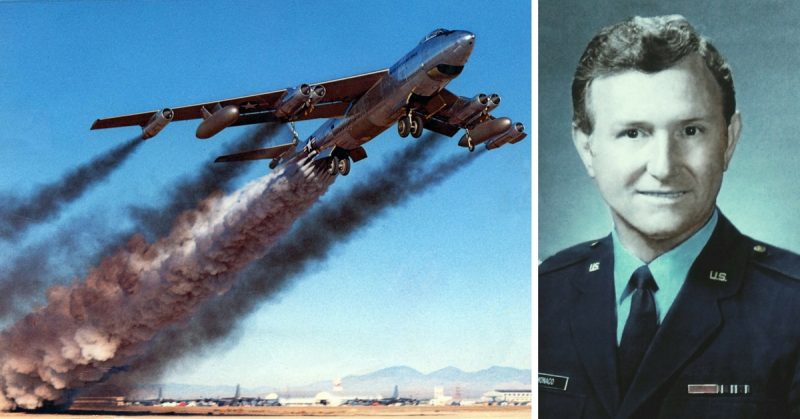

“Upon graduation (in 1952),” said Monaco, “I was commissioned a second lieutenant and transferred to the 43rd Bomb Wing with the Strategic Air Command (SAC) at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas.” He added, “From there, I was reassigned to Davis Monthan Air Force Base at Tucson, Ariz.”

As noted in the book “Bigger Bombs for a Brighter Tomorrow” by John M. Curatola, the Cold War legacy of the SAC and its crews stretched forth more than 50 years following the close of World War II and “provided considerable deterrent power for the U.S. military and offset the Red Army’s numerical superiority.”

Curatola added, “Sitting atop the most potent and powerful weapons ever devised,” wrote Curatola, the men and women of the SAC stood as the bulwark against potential Communist expansion.”

After completing advanced training as a personnel officer in Texas and Arizona, Monaco was given temporary duty assignments, resulting in his transfer to Brise Norton Air Base in England. It was here, Monaco explained, that he served under General Curtis Lemay—a World War II veteran who at the time commanded SAC and later went on to become the fifth chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force.

“Lemay was a very compassionate leader, but he was also very definite about what he wanted to accomplish,” said Monaco. “He wanted to reach the enemy and he knew that enemy was Stalin.”

For three-month periods, Monaco further explained, units would rotate in and out of Brise Air Base due to the “tedious nature” of their assignment in deterring the Soviet encroachment into Eastern Europe.

“A piece of serving as a deterrent was having aircraft in the sky 24/7,” he said. “This required us to work with squadron commanders, wing commanders and so on, to have oversight of all of our personnel and equipment. He added, “We had to make sure there were appropriate personnel at all times to maintain and operate the aircraft.”

While stationed in England, Monaco and several of his fellow airmen were temporarily assigned to help provide security for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on June 2, 1953, when she ascended to the throne of the United Kingdom following the death of her father, King George VI.

Following completion of his overseas duty, Monaco was transferred to Tucson, Ariz., in July 1953, where he met Mildred Pickett. The couple married later the following year and Monaco went on to finish out his active duty commitment with the 43rd Bomb Wing in September 1954.

“I eventually settled in Jefferson City (Mo.) and enrolled in law school at the University of Missouri,” said Monaco. “I continued in my military service in a reserve capacity by joining the 9698th Air Reserve Squadron (Air Force Reserve) located at the airport in Jefferson City,” said Monaco.

The veteran graduated from law school in 1958 and has since enjoyed a lengthy career as an attorney; however, throughout the years, his full-time civilian career continued to run parallel with his Air Force Reserve commitment.

“I was appointed as the Air Force Academy Liaison Officer and responsible for recruiting high school graduates from a territory in North Central Missouri,” said the veteran. “My mission was to interest qualified high school students to become cadets at the Air Force Academy in Colorado.”

During his early years as a liaison officer, Monaco noted, only men were allowed to become candidates for the academy. In 1975, women were authorized by Congress to attend the academy and General Stephan Allan, the Air Force Academy superintendent, was appointed by President Gerald Ford to make the announcement nationally.

“I requested that General Allan, who was the person I reported to as academy liaison, to make the announcement in Jefferson City,” said Monaco. “They agreed to make the announcement at the Missouri Hotel (now the site of the Missouri Baptist Building) before an audience of nearly 600 people.”

During his 28 years in the Air Force Reserve, Monaco was also afforded the opportunity to teach the Uniform Code of Military Justice to local high school students, introducing them to courtroom proceedings. In 1990, Monaco retired from the reserves, having risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Many milestones exist in the military experience of the Jefferson City veteran, yet it was his time served with the Strategic Air Command during the early years of the Cold War that were some of the most memorable of his lengthy career.

“We had to work as a unit, think out solutions and everything we did was highly classified,” Monaco said. “In fact, it was so classified that people did not know what we did … including my parents.”

He acknowledged, “During the service, you learned to do what you were told, when you were told to do it and in the manner in which you were expected to do it. And although I don’t believe that I did anything spectacular, I certainly enjoyed my time in the Air Force.”