For four long days they resisted – to stage a dramatic last stand worthy of international attention.

At the first major battle since Marco Polo Bridge, a Chinese battalion mounted a determined defense of Sihang Warehouse in Shanghai, in what can only be described as a heroic, emotionally-charged last stand. The four-day battle in October 1937 saw 1st Battalion, 524th Regiment of the famed 88th Division of the Chinese National Revolutionary Army (NRA) stubbornly holding ground against the Imperial Japanese Army’s Elite 3rd Division. But why have these men – merely 414-strong – came to be known as the ‘800 Heroes’ of Sihang Warehouse? And why did they stay behind to hold a non-descript warehouse?

It was all down to propaganda.

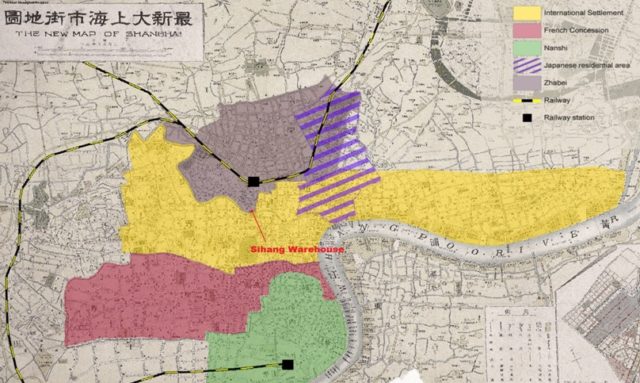

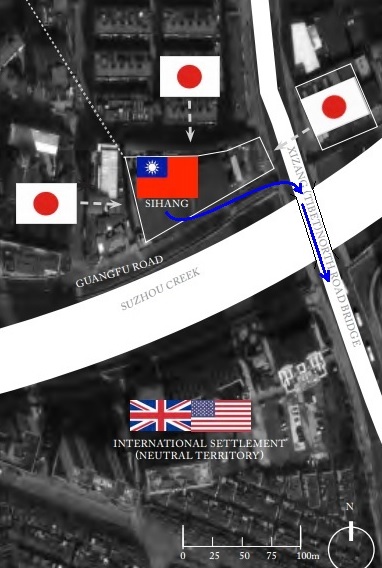

The defense of Sihang Warehouse, a household patriotic tale in China, had no obvious tactical value. The warehouse, a 25-metre tall six-storey concrete building, stood on the bank of the Suzhou River, in Zhabei disctrict on the edge of Chinese-administered Shanghai bordering foreign concessions. In other words, it was not a key rearguard position for the eastward-retreating NRA forces. Being just across the river from foreign concessions, however, meant that Sihang Warehouse offered Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek a unique public relations opportunity – to demonstrate China’s resolve in front of international eyes.

1937 was the first year of all-out war between China and Japan, and although the Second Sino-Japanese War began in 1931 with the Mukden Incident and Japan’s annexation of China’s northeastern provinces, the Western world was still extremely reluctant to assist the outgunned Chinese while still preoccupied with appeasing rising European threats. Germany and the Soviet Union were the only powers who aided China’s struggle in any meaningful way. The 88th was the result of German assistance – it became one of the few German-trained and equipped divisions before Nazi Germany withdrew aid to the NRA under Japanese pressure. It was very fitting, then, that the 88th was specifically chosen by Chiang as the only division to stay behind in the final days of Shanghai’s defense, in a bid to garner desperately-needed foreign military support. The 88th was under General Sun Yuanliang’s command. Its divisional HQ? Sihang Warehouse.

Upon receiving Chiang’s orders for a last stand, both Sun and his Military Region superior, General Gu Zutong, protested. They knew this suicidal order meant that the 88th would likely be annihilated – Sun was naturally protective of his own men, while Gu also had a sentimental attachment to the division as its former commander. Instead of wasting a division, the generals successfully petitioned for Chiang to approve the deployment of a regiment. Even so, Sun was unwilling to sacrifice 1000+ troops for propaganda, proclaiming that the same result could be achieved no matter how many men were sacrificed. Still, a mere battalion was not enough for a layered defence-in-depth – a closed defense of a single strongpoint was the only option. So 1st Battalion of Lieutenant Colonel Xie Jinyuan’s 524th Regiment was selected for the mission, and the 88th’s Divisional HQ was selected as the site of the imminent battle.

As the rest of the 88th retreated, 1st Battalion converged on Sihang warehouse, bolstered by additional volunteers and a machine gun company who provided their only heavy weapons – 4 Type-24 Maxim Guns (licensed copies of the German WWI MG 08). The 414 men tirelessly reinforced their fortifications, manufacturing sandbags with the warehouse’s grain sacks while burning down neighboring structures to create an open kill zone. These men were mostly raw recruits from Hubei, having joined the NRA within the past three months in response to the Japanese invasion in July. The NRA command was evidently aware of their numerical and firepower inferiority – they deliberately continued to label 1st Battalion as ‘524th Regiment’ in all communications to feign strength that Xie’s men desperately needed. Clearly, the odds were stacked against these young souls.

In the days to come, however, they defied the odds.

On 27th October, hours after the Chinese general retreat from Shanghai, 3rd Division IJA – nicknamed the ‘Lucky Division’, reached Zhabei district. As Japanese scouts entered 1st Battalion’s perimeters, waiting NRA soldiers immediately shot around 10 of them with their reasonably accurate copies of the German Gewehr 88 and Karabiner 98k. A Chinese recon platoon then probed the advancing Japanese force, only to be forced back by the sheer firepower of a whole company of attacking Japanese on the west flank. When about 70 Japanese troops stormed their way into a ground floor corner of the vast warehouse, Chinese defenders simply lobbed grenades and mortar rounds from upstairs, killing seven and wounding 20-30 in a deadly ambush. In return, Xie lost 2 of his soldiers on the first day.

That morning, no civilian knew of this plan for a last stand, but when a girl guide named Yang Huimin noticed a British soldier throwing a pack of cigarettes over to Sihang Warehouse from the concessions checkpoint, she got curious. When the British soldier told her the cigarettes were meant for the NRA defenders, Yang asked him to tie a note to the next pack of cigarettes, asking whether the defenders needed any supplies. Upon receiving a reply note requesting ammunition and food, the girl guide rushed to notify the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce. Thanks to her, all major papers published front-page stories of the ongoing gallant defense on the morning of 28th October.

Waves of Japanese attacks on the second day were fought off by the defenders, who held onto the warehouse’s high ground. The Japanese were restricted in their tactics – not yet prepared to fight the Western powers, the IJN dared not use mustard gas or aerial bombs so close to the foreign concessions. Finding himself on more of a level playing field with the IJA than any other Chinese commander in 1937, Xie confidently inspected his battalion’s defenses, shooting and killing a Japanese MP himself – from a full kilometer away – after noticing an enemy squad advancing. Even when Japanese soldiers occupied the neighboring bank building, they could not overrun the Chinese. Crucially, though, they successfully cut off water and electricity supplies to Sihang Warehouse.

Rumors of the defense spread like a patriotic wildfire throughout China, spurring many civilians to line the foreign bank of the Suzhou River, just to cheer their soldiers on. More importantly, many more sent supplies through the Chamber of Commerce to aid 1st Battalion. Feeling the noose tighten around his battalion as the second day of combat wore on, Xie requested that the Western forces take 10 of his wounded into the foreign concessions, under the cover of darkness. At night, trucks arrived with much-needed food, clothes, and morale-boosting letters from supportive civilians, returning to the foreign concessions with the wounded.

It was then that the legend of ‘800 Heroes’ was born, etched into history by 414 soldiers.

That morning, the papers had estimated vastly different numbers of defenders, ranging from 150-800. Keen to feign strength for morale and deterrence, Xie ordered the evacuating wounded to tell the outside world: ‘When they ask you how many of you are defending Sihang Warehouse, you tell them there are 800. Never let them know we are a mere battalion – the enemy would be more ferocious if they knew we are this few’.

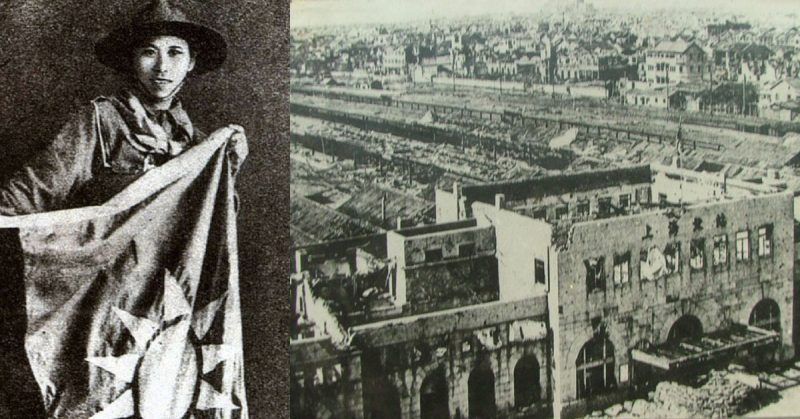

In the day, people had observed the demoralizing sea of fluttering Japanese flags surrounding Sihang Warehouse. So, on the same night, the Chamber of Commerce sent the brave girl guide Yang to bring a Chinese flag to the warehouse, to uphold both the morale of the defenders and the public. Before Yang returned to the concessions, she asked the men what their plan was.

The answer was short and clear – to defend the warehouse to the death.

Deeply moved by the battalion’s determination, Yang asked for a list of the men’s names, so that their glory might endure forever. Still intent on feigning strength, Xie gave her 800 names from the full regimental list of the 524th. The tactical deceit was now complete.

On the morning of the 29th, the flag of the Republic of China was raised on the roof of Sihang Warehouse on a makeshift bamboo flagpole, amidst the cheers of Shanghai citizens across the river. The Japanese, acutely conscious of the morale effect this symbolic act was having, immediately sent fighter-bombers to strafe and bomb the roof. Equipped with just two antique Maxim guns, however, the Chinese warded off all enemy planes, keeping their flag flying. Japanese pilots, weary of mistakenly hitting the foreign concessions, gave up on the raids after numerous passes.

Having licked its wounds from 2 days of constant combat, and having thus far failed to take the only Chinese strongpoint remaining in Shanghai, 3rd Division IJA launched the fiercest attack yet with overwhelming firepower. By midday, Japanese artillery hurled shells at the warehouse, covering the advance of light tanks and infantry. The intense bombardment, while ineffective against well-covered NRA troops within the warehouse’s thick walls, started chipping away at the building’s structure, even providing the defenders with brand new firing ports on the windowless west wall. When Japanese ladder parties started climbing towards the 2nd floor, Xie wrestled the rifle off of their point man, shoved the attacker out of the building, shot the second Japanese and pushed the ladder over.

Little by little, the Lucky Division is piling the pressure onto 1st Battalion. Things really got desperate in the afternoon, when one gravely-wounded defender decided to jump off the roof with armed grenades, killing 20 odd attackers. Faced with such unprecedented determination, the Japanese halted infantry-led assaults as night fell, focusing instead on artillery bombardment and machine tunneling towards the warehouse.

Meanwhile, each move by the Japanese was carefully observed by Chinese citizens from the foreign concessions. These concerned civilians warned the defenders by telephoning the warehouse or by putting up large posters containing relevant messages. One way or the other, the defenders were endowed with battlefield intelligence which prevented the Japanese from launching a real surprise maneuver. As 3rd Division IJA sent in more armored cars under heavy artillery cover – only to see the armored cars destroyed – Westerners became anxious to stop this fighting so close to their concessions. Pressured by the Japanese, concession representatives sent a letter on the 29th to the Chiang Kai-Shek’s government, lobbying for a ceasefire for humanitarian reasons. An agreement was eventually reached between China and the British Major General Telfer-Smollett, by which the Western Powers would allow 1st Battalion passage through the concessions to retreat westwards, to join the rest of the 88th Division.

General Iwane Matsui, commander of IJA 3rd Division who would go onto play a notorious role in the Nanking Massacre, agreed to uphold a ceasefire while the defenders evacuated – only to immediately renege on his word once the retreat commenced. In return, an enraged Xie had to be persuaded by his own men to abandon the fight to the last man. Despite Japanese violation and aggression, at midnight of 1st November, 1st Battalion successfully retreated into the concessions with 376 men, having killed more than 200 enemies.

American journalist Edgar Snow wrote of the Battle of Shanghai that it was ‘as though a Gettysburg were fought in Harlem, while the rest of Manhattan remained a non-belligerent observer.’ Indeed, it was right in front of western eyes that the gallant defense of Sihang Warehouse played out. Chiang has achieved his propaganda objective, winning global awareness of China’s struggle in return for an emotional drama of blood and sweat. This, however, was not to last.

International aid to China did not receive the much-needed boost Chiang expected – no other foreign power sent aid comparable to the limited assistance that the Soviet Union was provided, mainly to the Chinese Communists. After Sihang Warehouse, China still had to wait until 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour and declared war on Britain and the United States, before any meaningful Western help arrived. Until then, China fought alone.

For the survivors of 1st Battalion, it felt like a betrayal. Although they suffered only 10 killed and 37 wounded, Chinese soldiers must’ve felt immense injustice when the British, too, reneged on their promise of passage for Xie and his men to reunite with their division. Upon crossing into the concessions, the Chinese were immediately disarmed and interned by the British, under diplomatic pressure from Japan. The soldiers were allowed to keep their military routine, without weapons, in their internment camp, raising their flag and singing their anthem every morning, while civilians were free to visit their heroes. This internment went on for four years, when the Japanese, following Pearl Harbour, finally invaded the concessions and took the men prisoners, sending many to hard labor or further imprisonment. The lucky few were able to escape, rejoining the NRA in Chongqing. Xie was not one of them – he was stabbed by his own men, who were turned by the puppet occupation Chinese administration, in April 1941. Mourning the tragic loss of a people’s hero, as many as 215,000 civilians came to pay their respects over three days.

Despite all the sacrifice, betrayal, and tragedy, the brave souls of 1st Battalion had accomplished their mission. They defended the warehouse in a brilliant tactical feat, while garnering all the international attention they possibly could from an extremely reluctant West. Although help would not come for another 4 years, they proved an important point – China will fight on, no matter the cost. For this, the Chinese people will forever be grateful.

Author: Norton Yeung

All Photos Provided By The Author

Bibliography:

- China Youth Service & Recreation Center, Leading 800 Heroes in the determined defense of Sihang Warehouse – Lt Colonel Xie Junyuan (in Chinese) http://www.chinayouth.org.hk/heroweb/TSE.htm

- Henriot, Christian (2009) ‘A Neighborhood under the Storm: Zhabei and Shanghai Wars’, European Journal of East Asian Studies, Vol. 9, no. 2 (2010), pp. 293-321 Online version: http://www.virtualshanghai.net/Texts/Articles?ID=77