War History Online presents this Guest Article from Ned Forney

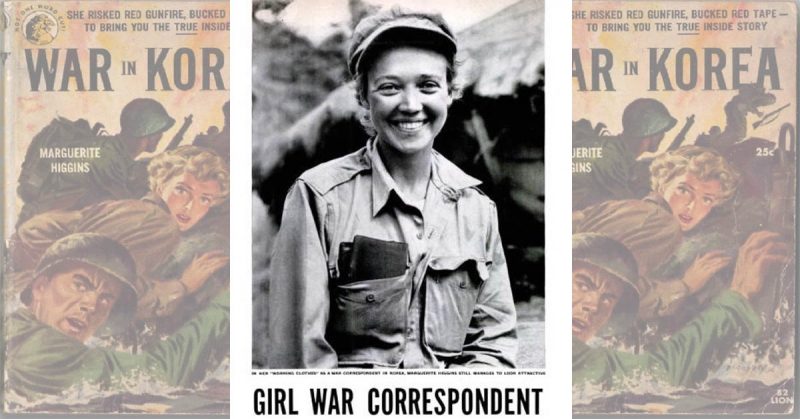

In a few weeks, the 67th publication anniversary of a little-known Korean War book will quietly come and go. The non-fiction work won’t make headlines, and its author won’t be remembered in editorials or magazines. But things were different in 1951. The book, War in Korea, and its author, the award-winning Marguerite Higgins, were hugely popular that year. Higgins had spent six months in Korea, from June through December 1950, reporting from the front lines of some of the bloodiest battles of the Korean War.

Although Ms. Higgins’ remarkable life has been largely forgotten, her book and views about why we should remain vigilant against the tyranny of Communism and dictatorships are as relevant today as they were 67 years ago.

The Indomitable Ms. Higgins

Born in 1920 in Hong Kong, Marguerite seemed destined for a life of adventure and travel. Her father, an Irish-American who had served as a World War I pilot and married a French woman, settled in Hong Kong for business reasons. The couple’s first and only child, Marguerite, was born a year later. Growing up in a thriving, cosmopolitan city with a French mother, the young Marguerite, or Maggie, as she was affectionately called, spoke fluent French and Chinese by the age of 12.

After the stock market crash of 1929, her parents returned to America, but Maggie’s love for Asia and international events had already taken hold. She graduated from UC-Berkeley in 1941 with a degree in French and later earned a master’s in journalism from Columbia University. She was soon working for the New York Herald Tribune and hoping to be sent overseas to cover the war in Europe. But being a war correspondent was for men, not attractive, blond women, she was told.

But Maggie persisted. By 1944, she had persuaded her boss to send her to France and was soon attached to US Army units moving into Germany. She was one of two American reporters to enter Dachau concentration camp on April 29, 1945, when it was liberated by American GI’s . What she saw there made a lasting impact on her. As a young reporter, she had witnessed some of the most historic – and horrifying – events of the 20th century.

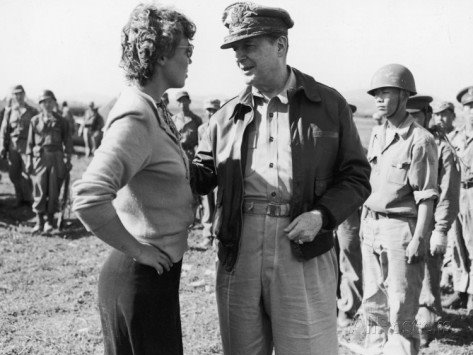

She had also ruffled feathers. Her gutsy and assertive style, along with her good looks and relentless pursuit of “getting the story,” had intimidated many of her male colleagues. She was only making headlines because of her shapely figure and attitude, they protested. Some even complained, without facts or proof, that she was using her alluring smile to get preferential treatment from the military brass.

Any reservations about her being a professional and noteworthy journalist, however, were soon erased. Ms. Higgins, now the Tribune’s Tokyo bureau chief, was sent to Korea just two days after North Korea’s invasion of the South on June 25, 1950. The most important and demanding assignment of her career had begun.

Reporting From Korea

Maggie spent the next six months on the war-ravaged Korean peninsula reporting on nearly every major military operation. From the fall of Seoul and Inchon Landing, to the Battle of Chosin and Hungnam Evacuation, she marched, lived, and suffered with US soldiers and Marines fighting in the streets, over the snow-covered mountains, and on the landing zones and beaches of Korea. Her ability to endure sleepless nights, minimal food, and constant danger earned her the respect of every GI she met. One Army officer remarked, “We’ve learned Maggie will eat, sleep, and fight like the rest of us, and that’s a ticket to our outfit any day.”

The feeling was mutual. Ms. Higgins’ deep respect and admiration for the young men struggling to fight and win a war many Americans were not interested in made her a relentless advocate of the common infantryman, or “grunt,” on the ground. She became their greatest champion and was determined to tell their remarkable, heroic, and often heartbreaking stories. She had become so attached to the men on the front lines that she frequently risked her life to tell what she believed was the “real” story of the war, the story of the average soldier and Marine. Many of her colleagues said she was reckless and foolhardy, but she pressed on.

She landed with the Marines at Inchon’s Red Beach, a “rough, vertical pile of stones,” and climbed over a seawall with “improvised landing ladders topped with steel hooks.” Within seconds, North Korean troops began pounding the Marines with “small arms and mortar fire,” even throwing “hand grenades down at us as we crouched in trenches.” Despite the danger, Maggie was with “her” Marines and never hesitated. She would stay with the First Marine Division through its push into Inchon and Seoul and would later rejoin the unit at Chosin. Reporting on the Marines at the epic Reservoir battle, she would write, “The marine breakout [from Chosin] is symbolic of how a military situation at its worst can inspire fighting men to perform at their best.”

In her book and articles, she told stories not only about Americans and Koreans fighting for their lives, but also about refugees that filled every town, village, road, and bombed out building in Korea. Heading into Seoul on a jeep during her first day on the peninsula, she saw thousands of refugees fleeing the capital. The North Koreans were on the outskirts of the city and everyone was desperately trying to leave before the Communists arrived:

The road to Seoul was crowded with refugees. There were hundreds of Korean women with babies bound papoose-style to their backs and huge bundles on their heads . . . I thought then, as I was to think often in later days, ‘I hope we don’t let them down.’

Her front-page Herald Tribune pieces would be read by millions, and her uncensored, often disturbing stories of refugees and GI’s dying in Korea, a country many Americans had a hard time locating on the map, mesmerized and shocked the nation. Within months of returning to the States, she became the first woman to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for international journalism.

A Woman With Uncompromising Convictions

Higgins’ time in Korea proved she was a war correspondent as good as her male colleagues. Maybe even better. But just as importantly, it had given her a platform to express her opinions on what should and shouldn’t be done in a world threatened by Communism. She wasn’t one to mince words:

Many more Americans will have to be tough enough and spirited enough to want to fight these dirty, stinking battles. We are engaged in a kind of international endurance contest, and the Communists are the first to recognize it.

In the final pages of her book, Higgins summed up what today’s Secretary of Defense, Jim Mattis, repeatedly says to our men and women in uniform: “Toughness on the battlefield is important because it saves lives.” But then she added a final caveat, “There will have to be equal toughness at home.”

Marguerite Higgins died in 1966 from complications of a parasitic disease she’d contracted while reporting in Vietnam. She was only 45. Her bravery, strong convictions, and pioneering spirit left a legacy we can all be proud of.

Ned Forney Website