By Guest Blogger Szymon Serwatka

All photos provided by the author

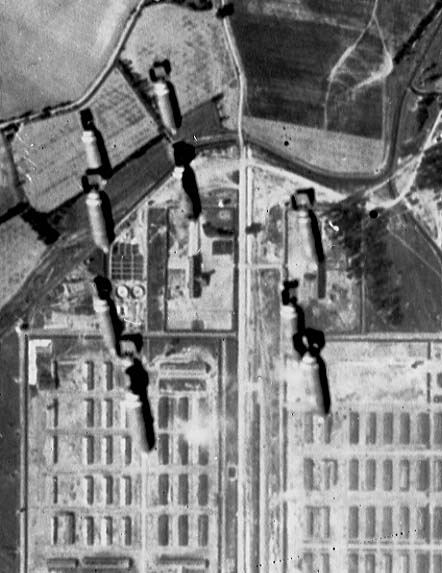

On Friday, September 13th, 1944, the 15th Air Force targeted the Nazi fuel industry in Silesia, in south-eastern Germany. Over 800 aircraft, half of which were bombers took off from Italy and took the northern heading. The 485th Bomb Group was scheduled to hit Oswiecim/Auschwitz IG Farben synthetic fuel factory. This was the second time this factory was bombed.

The first visit was paid by B-17s of the 5th Bomb Wing (15th Air Force) on August 22nd, 1944. The third and last time Auschwitz IG Farben was attacked was in December 1944.

Bombs hit the target but some fell short and exploded in the Auschwitz I concentration camp area. Several prisoners and fifteen SS-men were killed. The wounded prisoners were placed in the camp hospital where usually deadly experiments were performed. But this time the wounded received flowers and were served proper food.

The camp commander visited them and he was accompanied by crowds of Nazi journalists and photographers who eagerly documented the “barbarism” of the Allied air forces and the “good” treatment the prisoners received from the Nazis.

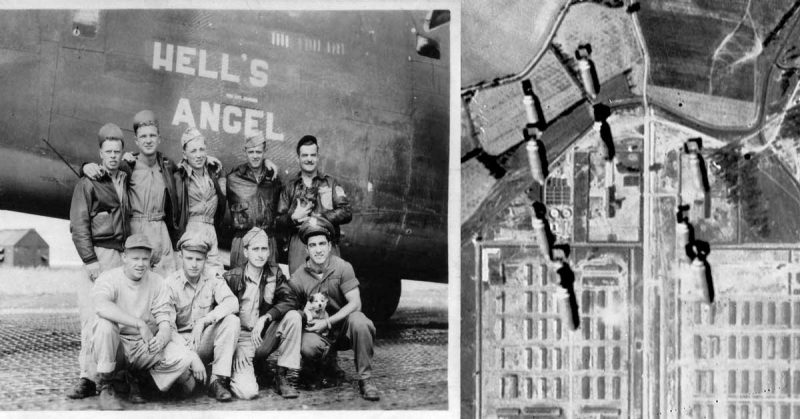

Some of the B-24 “Hell’s Angels” crew had bad feelings about the mission because of the date of Friday 13th. But the call to duty and the hope to finish the combat tour soon prevailed, supported by the experience and self-confidence of the airmen. This mission was to be the end of the combat tour for the pilot, Capt. Lawrence, co-pilot Lt. Hall, navigator Lt. Winter, bombardier Lt. Pratt, radio operator Sgt. Eggers, and the tail gunner, Sgt. Nitsche.

After this one, they were to get a ticket home. The other crew members on that mission were the radio navigator, Lt. Canin, lead navigator trainee, Lt. Blodgett, top turret gunner Sgt. Christensen, waist gunner Sgt. Kaplan. The oldest man in the crew was the other waist gunner, Sgt. MacDonald. He was 27 years old, but some of his black hair turned white within these few months of the combat duty.

Navigator Winter remembered that the flight to target was very long – almost four hours. Around midday the formation reached the Initial Point of the bomb run and turned directly towards its target at the altitude of 20000 feet. Over the target, the bombers flew into the flak barrage that lasted seven to eight minutes.

Christensen recalls the aircraft to have been new, silver and shining. The name was still to be painted on the nose. Christensen was in the top turret watching out for the enemy fighter planes. When he saw the cloud of the black flak bursts over the target, he was sure they would be hit. He asked for a parachute but there was not enough space in the turret to snap it on. A few seconds later the aircraft received a direct hit in the right wing. Winter screamed over the intercom that the engine number 3 was out. MacDonald tried to calm down the nervous voices of the other airmen. Christensen fell down from the turret and almost lost his consciousness because he had unintentionally cut out his own oxygen supply. He has survived only because of a fellow crew member. This other airman helped Christensen to get the chute on and pushed him out of the aircraft through the open bomb bay.

The crew members from the other aircraft in the formation always had to report on the shot down aircraft so that the fate of the crew could be reported on. Sgt. Allen from another crew of the 485th Bomb Group reported that the Lawrence’s B-24 was hit in the engines no. 3 and 4 and went into a spin just after “bombs away.” Two chutes were seen, then the aircraft began to disintegrate, hit the ground and exploded.

Who survived and who died could be confirmed only when the survivors were liberated at the war’s end. 70 years old reports reveal the further part of this tragic story. Winter wrote he had bailed out together with Pratt from the nose. They decided to do so despite the lack of command to bail out, because they could not see any feet on the rudder pedals. At the same time, Christensen was pushed out of the bomb bay and Canin and Blodgett followed him. Blodgett described his last moments onboard the B-24 with these words:

“My position was behind the pilots. When the waist gunner informed about an engine on fire I went down into the bomb bay with the fire extinguisher. There was no alarm bell nor command on the intercom to abandon the ship. Lt. Canin was the last person to leave the bomber and he had to use all of his strength to get out because the “Liberator” went into spin at this very moment. Lawrence and Hall were seen last in the cockpit, ready to jump. Most probably, they and the airmen from the tail were trapped inside by the centrifugal force. When I opened my chute, I could not see our plane, but a trail of smoke extending towards the southeast.” The ship exploded over Zygodowice. Lawrence, Hall, MacDonald, Eggers, Kaplan and Nitsche died.

The eye witness of the disaster, Ferdynand Bałys of Zygodowice recalls: “It was around noon. I remember my mom saying not to go anywhere because lunch was ready. This aircraft became larger and larger and it was clear she could not maintain altitude. She was shining in the sun so much that looking at her was barely possible. She was banking from side to side, the engines roared loudly as if it were a wounded beast.” The aircraft trailed burning fuel. Before the B-24 hit the ground, the fuselage fell apart and witnesses saw figures of airmen falling out. The engines with propellers fell one kilometer further. The trail of smoke stayed long in the air. In the distance, the chutes of the surviving Americans were descending slowly. A local girl working in a field with her father was badly burned by the burning fuel. She died 3 weeks later.

German soldiers ordered the fallen soldiers to be buried near the crash site. The local citizens marked the grave with a wooden cross and a small fence. The grave was frequently visited by local Poles, and Germans did not like it. Two sisters living close to the crash site were taking particular care of the grave. Germans threatened to send them to Auschwitz if they continue to put flowers on the grave. They continued despite the threats but were more careful.

In 1947 Zygodowice were visited by the American mission searching for American graves in Poland. The remains were moved to the American Military Cemetery in Belgium and to the USA. Poles never learned the names of their American heroes. Still, after the liberation, it was decided to erect a memorial dedicated to the “Hell’s Angel” crew. This remembrance was not liked by the communist regime, and this was probably the reason the secret police searched the houses in Zygodowice and the area. Most of the bomber’s remains were confiscated and it was thought that then politically incorrect fallen allies would be soon forgotten.

The communists almost made it. The tragic story of the young Americans was forgotten for almost 50 years. The remembrance was revived thanks to Zygmunt Kraus, who organized the exhibition in Wadowice and initiated the erection of a memorial in 1991 at the crash site. Upon his invitation, Vernon Christensen, one of the “Hell’s Angel” survivors, came to visit Wadowice and the memorial in 1994.

The memorabilia at the Zygmunt Kraus museum are exceptional. Many were retrieved from the soil during the search on the crash site. Some came from the local villagers and some were donated by the “Hell’s Angels” survivors.

Particularly interesting is a dummy with a complete combat uniform and equipment of a USAAF airman. Another rarity is an original “Liberator” propeller. Both the dummy and propeller were donated by the American friends. I would like to thank Zygmunt Kraus for making the source materials and photos available to write this story.

The author, Szymon Serwatka, has been researching US Army Air Force over Poland in WWII for more than 20 years. He offers WWII history tours to Poland, which include USAAF museum at Blechhammer and B-24 crash locations. Here is a link to The Blechhammer Tour.

All photos provided by the author

By Guest Blogger Szymon Serwatka