War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Before graduating from Tonganoxie High School in Kansas, Stan Putthoff realized he wanted to become a sailor and made the decision to enlist in the Navy’s delayed entry program. In 1970, just weeks following his graduation, he attended boot camp at the Naval Training Center in San Diego, beginning a period of service he believed would find him bobbing on the waves of the high seas rather than silently slicing through the ocean depths aboard a nuclear submarine.

“My dad and his brother had served in the Army in World War II and they talked about being in the mud and eating K-rations,” Putthoff recalled. “I decided that if I were going to serve in the military, I would go where there was three ‘hots and a cot’ (hot meals and a bed),” he chuckled.

Upon graduation from boot camp, he traveled to Great Lakes, Illinois, to attend advanced training as a machinist mate, spending the next four months learning system design and the operation of the turbines that propelled ships—what he referred to as “non-nuclear propulsion systems.”

He added, “When I graduated from the training in June of 1971, they gave me temporary active duty on the USS Wasp, which was an old World War II era aircraft carrier.” It was this initial two-month assignment aboard his first ship, he noted, that resulted in his decision to request duty aboard a submarine.

“One day while I was standing on the pier looking at the ship when I realized the engine room—where I worked—was below the water line,” he said. “Most of the other sailors on the ship worked in assignments above the water line.” Pausing, he added, “That’s when I decided that if I’m going to be working underwater, I want everybody that I serve with to be underwater as well so that we all have the same desire to make it back above the water.”

His request for submarine duty was approved and the young sailor was sent to Bainbridge, Maryland, for six months of nuclear power school, during which “two years of mechanical and nuclear engineering was crammed into six months,” he said. He then traveled to Saratoga Springs, New York, where he completed the nuclear power prototype school.

“We worked on a mock-up of a nuclear destroyer,” explained Putthoff, when describing the training he received in New York. “It was 12-hour days—part of it spent in a classroom the other learning to operate the nuclear power plants used aboard ships.”

Since he did well in the training, he remained in New York for three months of engineering laboratory technician school and received additional instruction in such areas as fission byproducts, boiler water chemistry and nuclear effects on water.

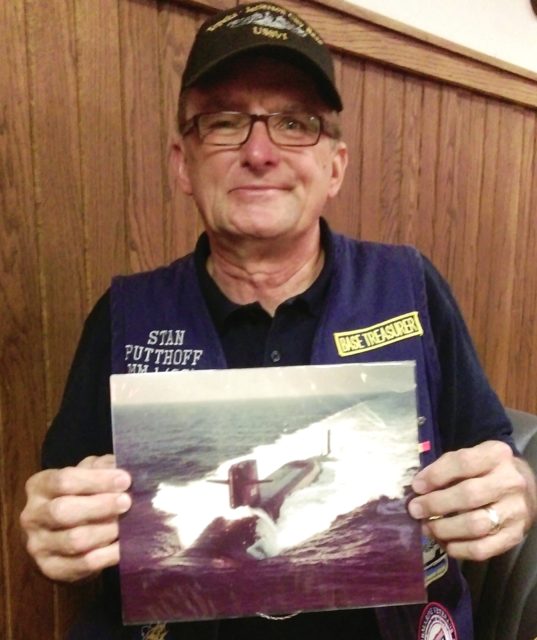

A little more than two years after he entered the service, in December 1972, Putthoff finally received his first submarine assignment and traveled to Rota, Spain, to report to the USS Thomas Jefferson—a nuclear-powered submarine that was launched ten years earlier.

While working in the engine room, Putthoff completed a two-month patrol in the Mediterranean aboard the submarine observing Soviet activity and engaged in other classified activities. After the submarine returned to Spain, it was turned over to their counterparts, while Putthoff and the sailors of the “Gold” crew traveled to New London, Connecticut, for three months of off-crew time consisting of leave and training schools.

The Gold Crew then traveled back to Spain and took the submarine on a North Atlantic Cruise, during which, Putthoff, recalled, they remained submerged for a period of 68 days.

In the summer of 1973, the submarine remained at New London to perform diving exercises and introduced cadets attending the U.S. Naval Academy to the daily rigors of submarine duty. That fall, the USS Thomas Jefferson traveled to Mare Island, California, where it resided in dry dock for an overhaul for the next 17 months.

The Gold Crew would then spend seven months in Pearl Harbor before flying to Charleston, South Carolina, to relieve the Blue Crew and take the submarine to the Bermuda Triangle for “sound trials”—testing the sub “to see if it was leaking sound into the water.”

Putthoff said, “After traveling (to the West Coast) to load torpedoes and test equipment, we went to Bremerton, Washington, to test fire torpedoes on a test firing range. After that, we went back to Pearl Harbor and I was transferred to the USS Sea Dragon to finish out my last two months of service.” He added, “I was discharged in October 1976.”

In addition to earning a bachelor’s degree following his discharge from the Navy, Putthoff married, raised a family and enjoyed a lengthy career at the Callaway Nuclear Plant, retiring in 2008 as a training supervisor. He remained employed as a consultant at the plant for seven years following his retirement.

The Fulton, Missouri, resident explained that his time in the submarine service may not resonate with the glamour and notoriety of others who have served their nation in uniform, but it was an experience bursting with stories of heroic service that have never been shared with the public.

“I view it as important to remember the time that Cold War sailors spent away from their families, missing important events so we as a nation could maintain the nuclear deterrent that kept our Cold War enemies in check,” Putthoff said.

“Although it is important to remember the overt actions by members of our military that have received recognition from the media, there are still many people out there whose deeds go unrecognized because of reasons of national security.” He affirmed, “We are the silent service (submarine service) and our job is to remain undetected—and we are very good at it.”