War History Online presents this Guest Article from Pietro Giovanni Liuzzi

During the German occupation of the Dodecanese, which took place after the fall of the Fascism, the Italian-Anglo-American armistice, and the British intervention, the commander of the region was General Ulrich Kleemann and later Otto Wagener.

The first was very concerned that if the overcrowded Italian prisoners had rebelled they could have overpowered the small number of German occupation troops. It was Hitler himself who realized this danger and sent personnel from Germany to take over the requisitioned Italian merchant ships in the Aegean. Thus began the transfer of prisoners from the Greek islands to Germany.

It was a massacre: the steamer Donizetti, on the night between 23 and 24 September 1943, was sunk by two British destroyers, Eclipse and Fury; The Sinfra, October 18 of that year, suffered an air attack and sank; Petrella, previously called Ayron before being requisitioned by the French, was torpedoed by the British submarine Sportsman on 8 February 1944 at the exit from the port of Suda.

The ships carried, piled in the holds, a human cargo of about 10,000 Italian prisoners sailing to Piraeus; out of them about 500 men were saved. The Oria, initially owned by the Norwegian Navy as Norda 4, carrying 4,115 prisoners, and due to a storm it drifted and ran aground near the island of Gaiduronisi, today called Patroklos; in total only 27 men survived.

“[…] The gruesome wrecks however represent only part of the many that occurred in the Aegean Sea during the tragic odyssey of the Italian soldiers taken prisoners […] If the Germans are condemned for their barbaric ferocity […] also the strategy of sinking transport loads of helpless people ordered by the British Admiralty should be considered among the facts quite not honorable carried out by the belligerent allies.” This is the outburst that Gino Manicone, a veteran of Rhodes concentration camps, writes in his book “Italians in the Aegean.”

General Kleemann tried to convince the Italian prisoners to enlist and to fight with the German troops; one of his associates, who was very active, was the Italian captain Francesco Cerulli and his dedication was such that he quickly won promotion in the field to major and then lieutenant colonel. Several prisoners enlisted to prevent the suffering of harsh imprisonment.

When General Wagener took over command it marked a critical period for the entire population and even more for the Italian prisoners who remained on the islands. He imposed a strict regime of detention, during which unspeakable actions were perpetrated so to push prisoners to reach pinnacles of homicidal madness.

After the surrender of the German forces, which took place on May 9, 1945, General Wagener and some of his collaborators were submitted to the judgment of the Military Tribunal of Rome. Wagener was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment for “having used violence against Italians non-participating in the military operations, causing the deaths of an unknown number of them by mistreatment, starvation, executions in retaliation for attempts to escape and lack of health care “. Similar behavior, according to the indictment, was conducted against the Italian prisoners of war interned on the island, many of whom had died as a result of ill-treatment, the poor food conditions, the lack of adequate medical care. The shootings were retaliation for even minor disciplinary infractions and escape attempts. Other contributors had lower penalties and others exempted from charges. The intervention of the Vatican and the pressures exerted by the German Chancellor Adenauer on Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi, urged Mr. Luigi Einaudi, the president of the Italian Republic, to grant pardons. Therefore no one spent the fixed imprisonment period in prison.

The motivation strongly supported by the Vatican action in comparison to the crimes committed in Rhodes by the ” group of Four” (General Otto Wagener, Lieutenant Walter Mai, major Herbert Nicklas, Corporal Johann Felten) was unbelievable; in fact, it states: “The Secretary of State has made here that Mrs. Wendula Wagener turned to the Holy Father asking an interest in obtaining a pardon in favor of her husband, General Otto Wagener and four other Germans, convicted by an Italian military court to sentences totaling 9 to 15 years’ imprisonment. It noted that the convicts have all children in the minority and are eagerly expected by their families, of which they are the sole support. ”

Wagener was sentenced to 15 years in prison for “complicity in violence and ill-treatment and murder against private Italian citizens” and “violence committed against Italian prisoners of war.”

The discovery of the wreck Oria

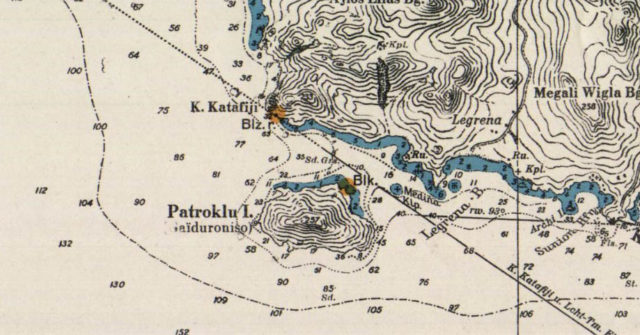

Aristotelis Zervoudis a Greek, professional diver, instructor, history buff and underwater researcher, since 1995, is credited with the discovery of the Oria wreckage. It occurred accidentally in 1999 because of information received by some local fishermen. He heard that to the east of the island of Patroklos there was a wreck of a ship.

He began the research and, after several attempts, he found military artifacts: some mess tins with inscriptions in Italian. This would suggest to him that the wreck was carrying Italian soldiers on its last journey. Two years later he was aware of a report which was

lodged in the German Naval Command archive indicating the name of the ship, steamer Oria, and the reason for the sinking.

In 2002, he published a report on the discovery and, in 2008, he was contacted by an Italian architect, Michele Ghirardelli, who had long been on the trail of his grandfather reported missing by the Italian authorities.

At the same time of the Aristotelis activities, in Italy Michele was researching documents. Other relatives of the victims joined him; the initial list of 30 names has increased steadily in the following months. Today there are more than 300 relatives, but some other families are requesting news about what had happened to their relatives.

The lists of personnel embarked on that disastrous journey were provided from the Historical Archives of the Italian Navy and the Red Cross. By these documents, it was possible to provide a certain fact to those who received the ministerial certificate with the term “dispersed”.

Finally, there were contacts between Aristotelis and Michele, also a diving enthusiast, and then a third diver joined in, Luciano de Donno. In 2011 the three organized an underwater research which was followed by others, one with the inclusion of an Italian Radio and Television diver-operator.

There were three broadcasts on the state television on the discovery : the first at night following the findings in the sea and, then, others broadcasting in the afternoon, seen by a greater audience, in February 2011 and in 2013 on the anniversary of the tragedy. Such events gave the opportunity to spread the news of the tragic voyage of the Oria steamship. Finally, the holocaust of such a tragedy received due recognition after being for 70 years lost in the depths of the Institutional Historiography.

The ORIA’s last sailing

The Oria was a cargo ship of 2,127 tons launched in shipyard Osbourne Graham & Co in Oslo in 1920; 86.9 meters long, 13.3 meters wide; it had a cruising speed of 10 knots. Once requisitioned by the Germans after the occupation of Norway it passed into the hands of the French Vichy authority, then it returned in 1942 to the Norwegians, to finish at Mittlemeer Reederei in Hamburg.

The Oria was one of the ships used since September 1943 for the transfer of the Italian internees. Its last sailing started from Rhodes on November 11, 1944 towards Piraeus: its human cargo, according to the list compiled in summary fashion during loading (probably due to interpreting factors), was made up of 4,046 Italians, including 43 Army officers, 118 non-commissioned officers and 3,885 soldiers in addition to 90 surveillance German soldiers and the Norwegian crew. Furthermore, there were also been stowed a large quantity of mineral oil and tires for wheels of heavy vehicles.

The Italians, once landed at Piraeus, were transferred to railway wagons for transportation to camps for prisoners in Germany or to Russia as laborers for the German units.

Italians were interned and not considered prisoners of war because they kept their oath to the King and the Motherland by refusing to join the Nazi fascism. They suffered harassment and hunger. They were crammed into the hold of the ship with the hatches closed from the outside because they could not come out on the deck of the ship, conditions were miserable. It lacked any respect for the transport of human beings in violation of safety regulations.

The next night at the start, the convoy consisting of the Oria and three German escorting ships, was hit by a heavy storm at sea and winds at SW 11 on the Beaufort Scale.

The master of the Oria, the Norwegian Bjarne Rasmussen, was ordered to move away from the coast for fear of ending up on the rocks. He did not for fear of running into enemy submarines already reported in the previous days. The stability of the ship, considering the overall load, was somewhat precarious. The freeboard from the waterline level was small. It began to take on water. The steering did not respond; and the ship drifted and shattered on the rocks of the island of Patroklos, near Cape Sounion. Only 25 miles short of meeting the final destination Piraeus.

The shipwreck was disastrous. Rescuers from Piraeus came two days late because of the stormy sea. In total, there were 37 saved in addition to the ship commander Rasmussen, the first motor engineer, 5 crew members, six German escort and a Greek. All the other men died trapped in the hold with no way out. The hatches were closed from the outside.

One of the survivors said that he was saved along with five other men because he managed to cling on a cabinet half-covered by water in a room that was revealed. Another of their companions died in an attempt to get out by swimming. They were rescued by an Italian tugboat from Athens; the crew was forced to cut metal sheet from the hull with a blowtorch. The ship was broken in two parts and those saved were in the forward area.

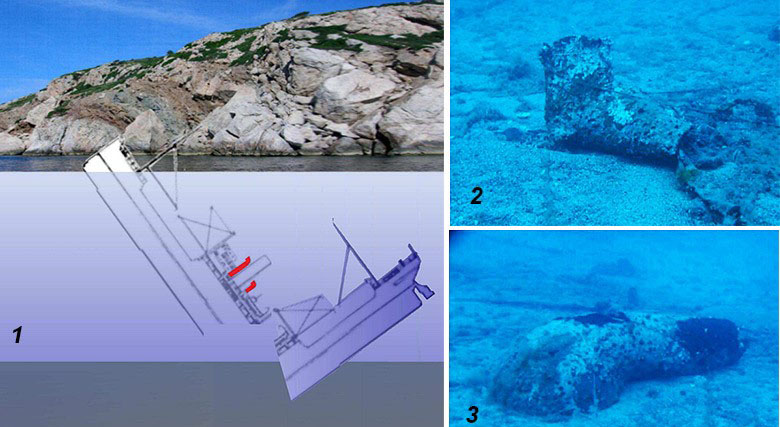

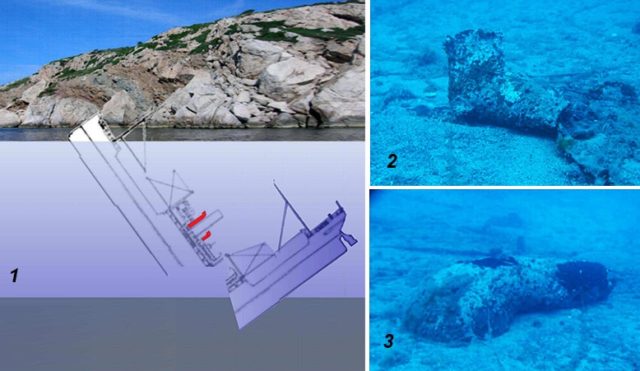

Photos 2 and 3. Wind sleeves (for aeration hold)

The bodies of the soldiers, now freed from the hold because of the breaking up of the ship, began floating out into the sea. About three hundred came ashore and were collected in mass graves by the work of other Italian military internees, in turn forcibly brought to the site in the following days. Two of the latter are living and provided valuable evidence. Many other bodies remained in situ or dispersed at sea, sometimes, even months after appearing kilometers away. For years they stopped fishermen pursuing their activities in that area of the sea; they dared not even to bathe in that water out of respect for the fallen castaways.

The group “Oria Fallen Relatives” have obtained economic as well as moral support from municipalities of Vaiano, Crispiano, Saronikos, CDSE foundation, to which must be added the contribution for the design of the monument by the Greek sculptors Thimios Panourgias and Maro Bargilli, which was inaugurated on February 9, 2014.

On the same occasion, a plaque was placed in the bottom of the sea. On the sea front of Souniou Cape, despite the appeals of the victims, there is no security against vandals who systematically violate the remains. The only protection, to date, is an UNESCO statement that defines the wrecks as the grave of those who perished in them. But the Oria being at depths from zero to sixty meters should have an explicit protection as “Shrine of the Sea.” Other Aegean areas are having an uncertain fate where over 15,000 Italian soldiers are buried.

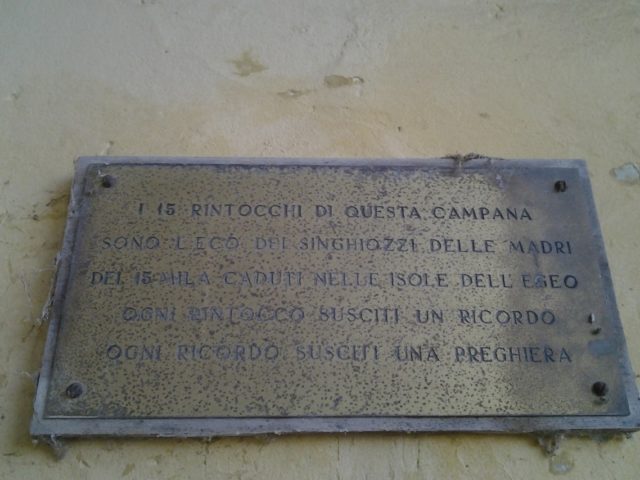

At Sermoneta, in the province of Latina, in a small church, Father Fino, chaplain at Rhodes, established the temple of remembrance of the Fallen and the Aegean Veterans, unfortunately, now in ruins. A plaque affixed near a bronze bell, states: “The 15 chimes of this bell is the echo of the sobs of the mothers of 15.000 Fallen in the Aegean Sea. Each chime arouse a memory, every memory gives rise to prayer. ”

Author: Pietro Giovanni Liuzzi

All images provided by the author.