This post is part of Culture.pl series and Stories From The Eastern West

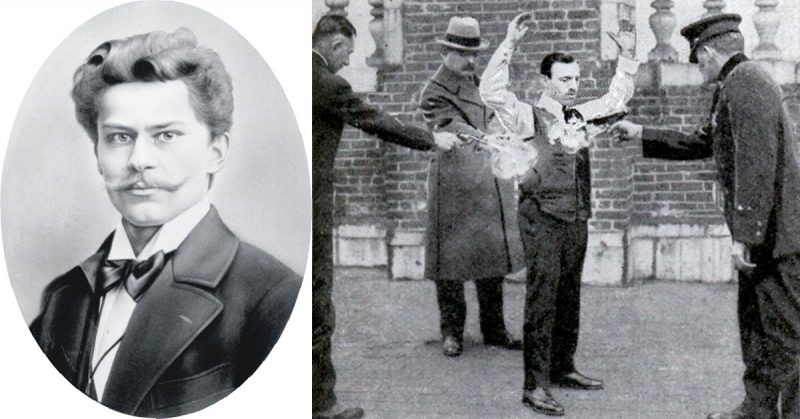

It’s 16th March 1897 in Chicago. Two men stand face-to-face in a huge square, one pointing a revolver at the other. It seems like the whole city is there watching: the mayor, the chief of police, a mob of spectators, and a priest, just in case…

The ‘executor’ fires his gun from a few feet away. The bullet hits and the victim keels over… but he almost immediately stands up again. He raises his hands, perfectly unscathed. People cheer. Everybody’s clapping their hands and throwing their hats in the air.

Did the shooter use blank bullets? Or did the audience just witness a magic trick? Neither. The bullets were real, it wasn’t a trick at all. But there was a bit of magic in what happened that day in Chicago. Let’s start from the beginning.

A monk who travelled across the ocean

The man who took that shot in the windy city went down in American history as Casimir Zeglen. He was, in fact, a Polish immigrant whose name was formally Kazimierz Żegleń (Ka-zhee-miesh Jeh-glen). He was born in 1869 in Poland, in a part occupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire at that time. At the age of 18, he joined The Congregation of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ and became a monk. A few years later, he emigrated to America where his life took a considerably different direction.

In America, Żegleń discovered he had a gift for inventiveness and he started working on developing durable materials. You’re probably asking ‘Why would a monk get interested in creating durable materials?’ at this point. Good question.

At the time of his arrival on American soil, US society was being troubled by so-called anarchists carrying out repeated attacks on public figures. Multiple assassination attempts were carried out and eventually, Chicago’s mayor, Carter Harrison Senior, was infamously murdered at his own house.

Reportedly, being a spiritual man, Żegleń was deeply distraught by these tragic events and decided to use his inventiveness to save people’s lives. And so, the monk started working on a bulletproof armor of a new kind, so light that people could wear them on top of or under their usual clothes.

A fateful autopsy

Until the late 19th century, the only bulletproof armor that had been proven to be reasonably effective was made from plates of metal and weighed far too much to allow unfettered movement.

The breakthrough came in 1881. A physician, named George E. Goodfellow from Tombstone, Arizona noticed, during a post-mortem examination of a man would who had been shot, that a silk handkerchief in the victim’s breast pocket had significantly reduced the penetration of one of the bullets.

Bewildered by his discovery, Goodfellow started investigating the bulletproof properties of silk and even constructed a vest that consisted of 30 layers of the stuff. Obviously, that many layers of silk is even heavier than a metal plate, but further experiments led him to reduce the number to 18. Though still a long way to go, it was clear that the invention of a fabric bulletproof vest was nearing reality. However, Goodfellow was a devoted physician more than anything else, and he abandoned his work with silk to return to his primary profession.

Go on, shoot me

This is where we go back to 16th March 1897 and that sunny square in Chicago. It was a common right to carry guns at the time but none of the invited audience, not even the mayor, knew exactly what to expect when they saw this duo face each other.

Żegleń’s assistant fires his revolver and hits him right in the torso. The impact is certainly painful but it does no harm to the inventor – he’s wearing a silk bulletproof vest of his own creation. It’s far thinner than any other that’s come before, at just 1 centimetre (0.4 inches) thick.

Żegleń came up with a peculiar way of sewing silk layers, which allowed making the most out of silk’s natural properties. He had hand-sewn the vest on his own but prior to the public test he had never actually tested it. He was lucky to survive. Further experiments proved that only a perfectly sewn vest was fully effective, and the level of precision required was dangerously absent in hand-sewn copies of his version.

Though he was a gifted inventor, Żegleń was not a trained engineer and unable to create a machine that would produce vests quicker and guarantee each was safe. He tried to find investors and manufacturers in America but couldn’t get backers, so in December 1897 he headed for Europe.

Enter the Polish Edison

Soon after arriving at Europe’s shores, Żegleń was directed to Jan Szczepanik (Yan Sh-Che-Pa-Nick), a figure referred to alternately as ‘the Polish Edison’, ‘the Austrian Edison’ (much to his disliking) and even ‘Leonardo da Vinci from Galicia’. He was a genius inventor, one of the first people to even think of colour film and the man who invented the telecstrocope – a television prototype that transmitted images and sound, enabling them to be viewed live remotely. With the invention of appropriate technology years later, his concept became a reality. Szczepanik also invented a few far less mind-blowing but fully operating machines, which made him well-known and well-off. Among these, he created a machine that could print decorative colour tapestry, a grand-grand parent of the colour printer.

Żegleń and Szczepanik teamed up and began working on technology that could automatically manufacture silk bulletproof vests. After only a few months, the production line was up and running and the vest publicly available to… only the extremely rich. Silk was always very expensive and its investors wanted to capitalise properly on their invention. A single vest cost around $800 (approximately $6,500 today).

Szczepanik was so delighted with the invention that he leaned hard on Żegleń to try buy the patent from him. He never succeeded. However, he was very successful in telling everybody that he was the inventor of the silk vest and conducted further public tests alone (they were 100% safe this time). His self-promotion went so well that until the present day, most Europeans who have heard of the invention think it was Szczepanik, not Żegleń, that was the silk vest’s inventor. The latter, during this promotion period, had gone back to America with his new-found knowledge to again try find investors to start a production line.

The double life of a silk vest

Szczepanik and Żegleń de facto parted ways after the machine that had automatically sewn them was constructed. Apparently, the Polish Edison was a better entrepreneur as he managed to popularise the product in Europe, even convincing Tsar Nicholas II to purchase one following another impressive test (though obviously, it didn’t save him from later execution by the Bolsheviks).

It reached its peak popularity after the silk fabric, sewn according to his method, was used to armour the royal coach of King Alfonso XIII of Spain and saved his life during an assassination attempt. A hand-made grenade was thrown at him and the shrapnel didn’t manage to penetrate the fabric.

Żegleń was far less successful in America. He veered away from his original plan and founded the Zeglen Tire Co and American Rubber and Fabric Company, which produced tubeless, impenetrable tires. Unfortunately, we know very little about the prosperity of these companies. We don’t even know the actual date of his death, indicating he didn’t become overwhelmingly rich and popular, to say the least.

Inches from an alternate history

So did the silk vest change history? It’s unclear, but our best guess is that it was actually very close in doing so. Both inventors used one of the best-known methods of promoting their products – they offered it to rich, famous and powerful people, such as King Alfonso XIII of Spain. But not all of them were smart enough to understand the invention’s usefulness.

In 1901, six months prior to the assassination of American president William McKinley, Żegleń had offered a vest to his security officer George B. Cortelyou, but was turned down for an unknown reason. Mc Kinley, in September 1901, was killed with a revolver, shot at him from a few metres away. A silk vest would certainly have saved his life.

Szczepanik is rumored to have offered his vest to Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and the legend has it that he was similarly turned down. Given that the assassination of the Archduke led to the outbreak of World War I, many like to wish that if only he had worn Szczepanik’s vest that day…

As much as we like alternative history theories, the Franz Ferdinand story seems to be an urban legend. There’s no hard evidence the vest was offered to him but, first and foremost, the vest probably wouldn’t have saved him even if he had worn it on 28th June 1914. Bullet and gun technology had vastly improved over the beginning of the 20th century, and by around 1910 Żegleń’s / Szczepanik’s silk vest had no guarantee of being impenetrable. It was in fact proven useless by 1913, a year before the archduke was killed.

Legacy today

The invention of the silk vest was revolutionary and paved the way for future bulletproof vests inventors. The proven idea that fabric could stop bullets led to the creation of modern armours that work on the same basis but use much more endurable, synthetic fabrics. Thousands of people, millions even, have since relied on this technology to stay alive in combat situations.

Sadly, although probably wisely, one thing that hasn’t been carried on is thrilling public tests similar to those performed by Żegleń and Szczepanik. Nobody seems quite so determined anymore to prove their product’s functionality by putting their own life in fatal danger.

As much as they must have been marvellous spectacles, remember: don’t try this at home!

Author: Wojciech Oleksiak

The story is available on iTunes / Apple Podcasts

Or visit Stories From The Eastern West to listen to it.