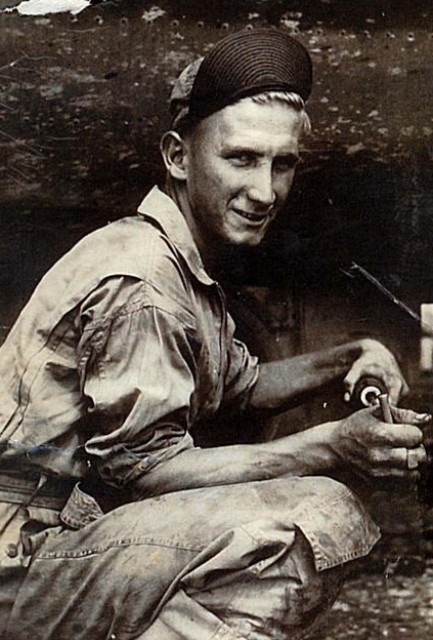

This is an article on veteran Bob Buell, who served in the Army Air Corps in World War II.

World War II veteran shares story of service on B-24 Liberator

By Jeremy P. Amick

Armed with a friendly wit and and a jovial temperament, a first impression of Bob Buell belies the profound adversity he endured during the Second World War.

“Where I grew up there were only two classes of people—poor and poorer,” Buell joked.

Graduating from high school in Bradford, Ct., in June 1941, Buell began working at a local factory. It didn’t take him long, however, to realize that the monotony associated with such a job wasn’t to his taste.

After visiting with an Army recruiter, Buell and some friends were convinced they should enlist to serve at the army base at Pearl Harbor. But when they returned the next week to sign their enlistment papers, the positions were no longer available.

“It’s one of those circumstances that saved my life, I guess,” Buell remarked. “A couple of months later the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.”

Buell was then persuaded to enlist in the Army Air Corps as an airplane mechanic. In October 1941, he was on the way to begin his basic and advanced training.

Completing the aircraft mechanic’s training at Seymour Johnson Field in Goldsboro, N.C., Buell stated that he and his fellow mechanics learned the basics of becoming “remove and replace artists.”

“We weren’t really mechanics,” he said. “If a part went bad or was broken, we just put a new one on. We really didn’t fix anything.”

Not long after he completed the school, Buell was on a troopship heading overseas in support of the war effort.“

Arriving in Folga, Italy, Buell was appointed as part of the ground crew on a B-24 Liberator—a heavy bomber used by the Allied forces.

While still serving in Italy, the Air Corps began asking for volunteers to serve as a tail gunners aboard the planes.

“I asked them what was in it for me,” Buell remarked. “They told me I could go home if I survived 50 missions.”

Torn between wanting to return home as soon as possible and longing to satisfy an 18-year-old’s lust for adventure, Buell made the transition from mechanic to tail gunner.

A member of the 15th Army Air Force Liberator Squadron , the young aviator participated in missions during which German-held targets throughout Europe were bombed. Yet his service wasn’t without its fair share of hazardous encounters.

On one occasion, the B-24 on which Buell was serving crashed on the landing strip when it lost power shortly after take-off. He and another gunner “stepped” out of a door near the rear of the plane.

“When a plane falls…you get out. We were carrying fragementiation bombs and you didn’t want to be near those.”

Buell experienced a similar incident when the plane he was on crashed near Rome, but the pilots were able land the plane in a way that none of the crew were injured.

Successfully suriving two overseas crashes and 50 combat missions, Buell returned to the United States in 1945—but soon discovered that injuries are a threat even on the homefront.

While onboard a B-17 Bomber practicing touch-and-go maneuvers on an Alabama airstrip, Buell was seriously injured.

During a training run one of the wheel assemblies was damaged, resulting in its collapse. This caused the nose of the plane to lean forward, leaving the tail sticking in the air.

Relying on instinct and prior experience, Buell evacuated through the hatch near the rear of the plane assuming the tail was near the ground. Unfortunately, the steep drop that followed left him severely injured with broken wrists, heels and legs.

Buell was sent to recover at a hosptial in Mobile, Ala., and in 1945 was discharged from the service.

After graduating from the University of Baltimore, he worked in the transportation industry for several years to include a stint with the Interstate Commerce Commission. In 1968, he was hired as an auditor with the Missouri Public Service Commission, where he remained until his retirement in 1991.

Reflecting on the circumtances that drew him into military service during the opening stages of World War II, Buell remarked, “Everyone has a responsibility to serve their nation—we all just did what we were supposed to do.”

With a wry grin, he added, “And as a dumb 18-year-old kid, it seemed a lot better than working in a factory.”

“Bad Bob,” as he was affectionately known by his friends, passed away in Jefferson City, Mo., in 2013.

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Jeremy P. Ämick

Public Affairs Officer

Silver Star Families of America

www.silverstarfamilies.org

Cell: (573) 230-7456