War History Online proudly presents this guest blog from Robby Houben.

The summer of 1914 marks the beginning of the First World War when the European allies and central powers declared war on each other. The small country of Belgium was quickly overrun by German invaders, until their advance was halted at the Ijzer river and the violence continued in the trenches during the next four years. Due to the quick advance of the modern and strong German army, history tends to overlook small acts of bravery that couldn’t change the tide of war. This article tells the story of Germany’s last cavalry charge at the battle of Halen.

In August 1914, the German empire launched an attack aiming to advance through Belgium and attack France from the north. Belgium was forced to defend its neutrality and manned its fortifications around the city of Liège, which lies close to the German border. Using new, powerful 420mm howitzers, the invading German army sieged the Belgian emplacements. The Belgian fortresses defended themselves bravely but didn’t stand a chance against Germany’s modern weaponry. They hold out for eleven days, which is much longer than the two days anticipated by the German command.

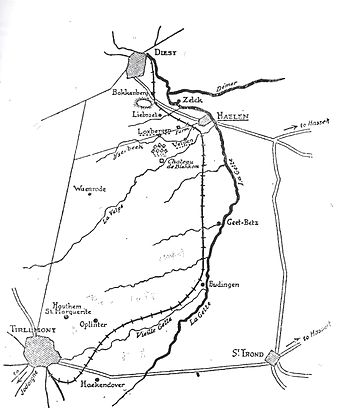

The Belgian main army was forced to retreat and establish a new defensive line at the Gete river. While the main German force was stalled at Liège, forward German elements were ordered to conduct reconnaissance towards the cities of Antwerp, Brussels and Charleroi. Belgian troops were sent to guard a bridge over the Gete river and block the German advance.

The Battle at Halen

The Belgian defenders, a force commanded by general Leon De Witte, consisted of cavalry from the Lancers and Guides regiments, a battalion of carabine-cyclists and two regiments of infantry with limited artillery support. Their opponents were the German II cavalry corps, lead by General Georg von der Marwitz.

Belgian cyclists (maneuverable infantry troops) were deployed in forward positions to defend the town of Halen. The rest of the Belgian forces were deployed in the area of Loksbergen and Zelk, on the western side of Halen. They found ways to use the difficult terrain and set up good defensive positions behind hedges, hollow roads and fields, covered by their artillery on the nearby ‘Bokkenberg’ and ‘Mettenberg’ hilltops. As part of his plan, the Belgian general De Witte instructed his cavalry forces to dismount and fight beside the infantry troops.

When the first German ‘Uhlans’ came in sight and charged their positions, the Belgian cyclists concentrated their fire and forced the German cavalry to turn back. However, it didn’t take long before the German reinforcements started to arrive. When their artillery shells began to rain down on the Belgian soldiers, they had to withdraw from the town together with the many remaining civilians. They took up positions close to a large farmhouse called the ‘Ijzerwinning’, in the middle of the Belgian defensive line to the west of Halen. The retreating Belgian troops tried to blow up the bridge leading into town, but the explosives only damaged the bridge. After the German vanguard repaired the damaged bridge with the gate of a nearby farm, they quickly occupied the town and became convinced of an easy victory.

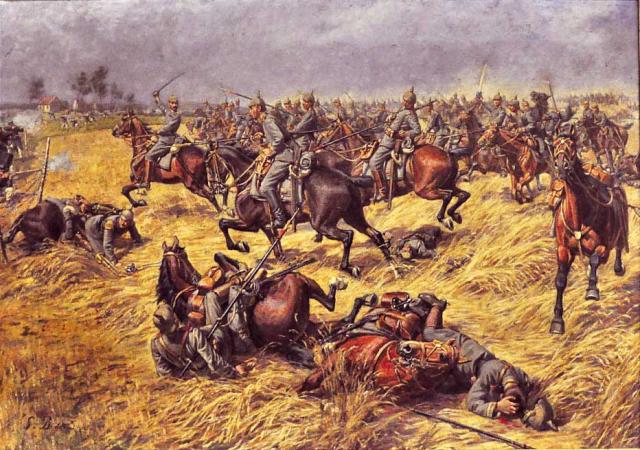

When the German forces started to gather in Halen for their assault, Belgian artillery opened fire upon them from their remote positions. German command reacted by ordering a cavalry charge with drawn lances and swords on the Belgian positions. With a swift advance, they hoped to overrun the Belgian troops and find a route to quickly eliminate the Belgian artillery.

As the German cavalry stormed the Belgian line, the defenders met them with volleys of fire from their Hotchkiss machine guns and rifles. The damage was horrific, but not only the concentrated fire from Belgian positions stopped the Germans. Almost invisible to the attackers, the terrain of their advance contained hidden gaps, wired fences and hollow roads which caused their horses to trip or slow down, creating vulnerable targets for the Belgians. The attack was repulsed and German troops were forced to retreat and regroup.

Aftermath

The battle at Halen was a tactical victory for the Belgian Army, although the battle only delayed the German advance shortly. The skirmish is considered a Belgian tactical victory, but in sheer numbers, Belgian forces suffered more casualties than the German invaders. The Belgians lost 160 soldiers and 320 troops were wounded. In comparison, 150 German troops were killed, 600 wounded and more than 200 were made prisoner. Besides these horrific numbers, a staggering amount of more than 800 horses died during the battle. Many of the Belgian fallen soldiers were buried in a nearby military cemetery. Nowadays there is a museum at the location of the conflict which displays artifacts found after the battle.

The battle was nicknamed ‘the battle of the silver helmets’. After August Coppens, a priest who lived nearby, visited the battlefield, he was inspired to write a poem about the havoc seen. He named the battle in analogy with a famous Flemish medieval battle, ‘the battle of the golden spurs’, where Flemish militia defeated an imposing French cavalry force. The name he chose was ‘battle of the silver helmets’, which refers to the many shiny silver cavalry helmets that littered the combat zone after the battle.

There has been much debate among historians about the importance of this battle at the start of the First World War. This skirmish, small in size as it may be, influenced contemporary views on modern warfare. The German cavalry attack is considered as one of the last sword-drawn cavalry charges in Western Europe. The well known German general Guderian even devoted one of the chapters of his famous book ‘Achtung: Panzer! to the battle, explaining how even the bravest cavalry charge is doomed against modern weapons.

All photos provided by the author.